|

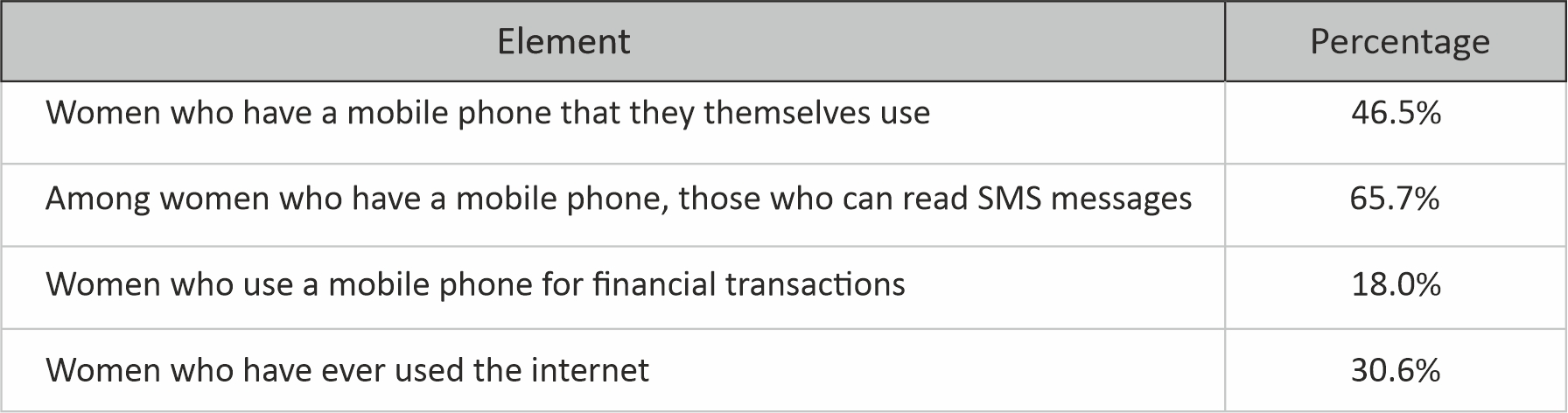

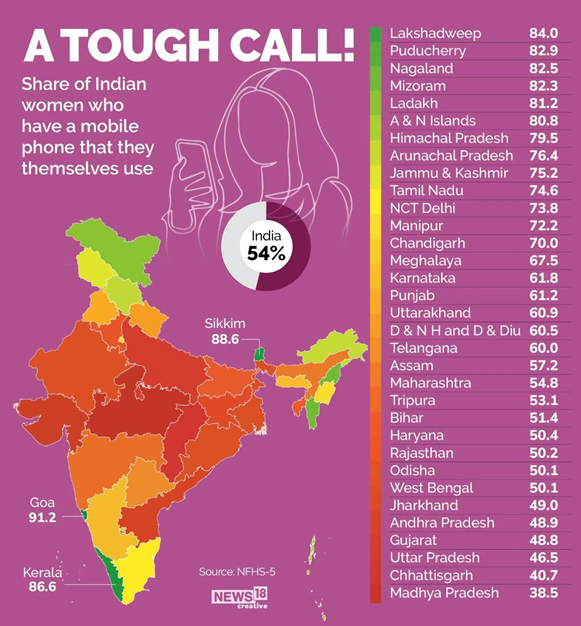

Access to information enables people to participate better in the world around them. In this regard, the past two years have been an eye-opener for us to realise that there was another divide growing among people, on top of the existing divides of class, gender, and so on. This is the digital divide, a barrier that was not created during the pandemic but had already existed. It separates those who have access to internet services and devices and the skills to use them from the rest. The divide is even wider when it comes to women. It goes deeper when we talk about women in rural India (see Table 1 and Figure 1). As most services offered by the public and the private sectors are intended to move online, this divide may lead to many more divides. The gender digital divide can only be bridged through digital inclusion. This again needs cohesive efforts of the government and the civil society. We, at Development Alternatives, have already taken several initiatives to bridge the gender digital divide and bring about a change at the mass level. Table 1: Technological empowerment of women (aged 15-49 years) in Uttar Pradesh as of 2019–21.*

*The data included

70,710 households, 93,124 women, and 12,043 men One of the projects for this purpose, TARA WE ADD (Technological and Rural Advancement through Women Empowerment by Annihilating the Gender Digital Divide), strives to bridge the gender digital divide by enabling women to use smartphones and enter into the economic workforce by utilising the technology. Women are now gradually bringing their businesses online, leading to the enhancement of household incomes. This project is being implemented in Lalitpur, Uttar Pradesh, supported by Reliance Foundation. Bringing women online, however, is not an easy task. The problem of access compounds the issue, as having a smartphone for a woman is perceived to be neither urgent nor important. Online education during the pandemic did provide an opportunity along with urgency to procure a mobile device even in a household with a monthly income as low as ₹ 10,000. Regular data services were being made available as it was critical to children’s education. However, now with children going back to school, most low-income families have discontinued data services. Smartphones can be seen lying in a corner of the house. Women’s ownership of the phone has not yet ensured that she is online.

Figure 1: Share of Indian women who have a mobile phone that they themselves use. This raises two critical questions: one is the availability of affordable data services, and the second is the connection between economic empowerment of women and her social empowerment. For affordable data services, efforts at the level of the government to bring decentralised technology are paramount. Civil society organisations also need to make possible access to frugal technologies that do not rely on external environments but rather use local resources to provide connectivity. The availability of offline content also needs to be pushed, so that women can consume it in their time and space. Coming to women’s economic empowerment, it is also important to co-create livelihood opportunities with women that work on ways of integrating technology with it. In TARA WE ADD, we introduced women to various livelihood opportunities, which ensured their connectivity and closeness to technology. For instance, we trained women as grassroots journalists, which required them to use smartphones to capture stories from the ground. Their further entry into the field will ensure their usage of smartphones and the role of the technology will get strengthened every day. Another example is of women like Sapna Jha, who after getting digitally literate under the programme went ahead to become a Vidyut Sakhi, under an initiative of the Uttar Pradesh government, and used technology to respond to the community's electricity bill payment issues. In ensuring digital inclusion, we are learning our lessons, some of which are:

Reference

GoI (Government of India). 2021. National

Family Health Survey-5. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, Government of India. Details available at

http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-5.shtml, last accessed on 9

September, 2022.

Ekta Kashyap

Tejashwani |