|

Business Case for Adopting Clean Technologies

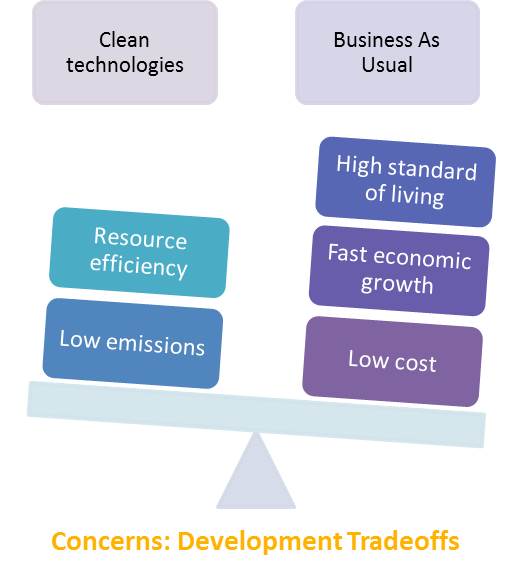

T he adoption of clean technologies, one of the key drivers of a green economy is often perceived to present tradeoffs between conflicting goals. On one hand, it provides much-needed climate action and resource efficiency, but on the other, it is thought to bring higher costs, slower economic growth and consequently lower standards of living than a Business As

Usual (BAU) scenario. growth and consequently lower standards of living than a Business As

Usual (BAU) scenario.

This article aims to demonstrate that contrary to the above concerns, a business case exists for transition to clean technologies. It explores the benefits in terms of financial implications, economic growth and social equity vis-ŕ-vis BAU. Financial Implications Contrary to popular belief, clean technologies can bring substantial financial benefits. According to Climate Policy Initiative (Nelson, et al., 2014), the transition to a low-carbon electricity system would bring the global community an estimated USD 1.8 trillion in financial savings during 2015-35. That is roughly the size of India’s GDP in 2013. Similar-sized savings are possible in transitioning to low-carbon transport. The question is how are savings of such magnitude possible when renewables involve higher capital expenditure and financing cost than non-renewables? The use of renewables allows us to save the high operating costs of extracting and transporting coal and gas. These savings far outweigh the high capital costs of renewables. Therefore, investment in clean technologies can be economically viable. Large-scale solar energy has achieved grid parity in India and rapid industry growth is already underway with forecasts of a USD 6-7 billion capital-equipment market and USD 4 billion in annual revenues for grid-connected solar generators over the next decade (Kaushal, et al., 2013). A similar story is expected of other clean technologies as resource efficiency will attempt to marry rising resource demand with limited availability and the costs of climate inaction will compel policy to incentivise clean choices. Economic Growth As in the case of any major technology shift, the transition to clean technologies will create jobs in some sectors and displace people in other sectors. A UC Berkeley research group modelled a scenario where 20% of U.S. electricity demand was met by renewables by 2020 and found that this would create a net 78,000 to 102,000 additional jobs – an increase of 91 to 119% over a scenario in which coal or gas met the entire electricity demand (Beinhocker & Oppenheim, n.d.). While not many such modelling exercises have been conducted for India, the prospects appear positive. Further, failure to adopt green technologies is not an option if sustained economic growth is a priority. According to the Stern Review, climate change could cost India and South-East Asia about 9-13% of their GDP by 2100. Up to an additional 145-220 million people could be living on less than USD 2 a day and there could be an additional 165,000 to 250,000 child deaths per year in South Asia (Stern, 2007). Social Equity Resource-efficient technologies reduce the requirement of natural resources per unit of output. The resulting conservation of resources benefits the poor, majority of who depend on these resources for their livelihood. The poor bear the greatest brunt of rising energy prices and the energy insecurity that follows. Therefore, investment in energy efficiency will benefit the poor (Beinhocker & Oppenheim, n.d.). Innovations in technology can solve some of the poor people’s most pressing problems. Solar energy innovations can electrify tens of thousands of villages in India without electricity. The development benefits of electrification are tremendous and needless to mention. Caveats While it is true that clean technologies can generate significant financial benefits, these benefits are realised only over a couple of decades. In the short run, they require substantial investment, which needs to be incentivised using appropriate policy tools. While the transition may generate jobs, the poor may not benefit from such opportunities if there are deficiencies in skills, health, education etc. Public finance must be directed towards enhancing the poor people’s capability to take advantage of opportunities. All the benefits described above are of course benefits ‘that could be’. The realisation of benefits is dependent upon effective policymaking that considers the interests of all stakeholders, especially the poor. q Harshini Shanker References · Beinhocker, E. & Oppenheim, J., n.d. Economic opportunities in a low-carbon world. [Online] Available at: http://unfccc.int/press/news_room/newsletter/guest_column/items/4608.php [Accessed 17 August 2015]. · Kaushal, V., Unni, A., Venkataramani, H. & Pant, M., 2013. Solar Power and India's Energy Future, s.l.: A.T. Kearney. · Nelson, D. et al., 2014. Moving to a Low-Carbon Economy: The Financial Impact of the Low-Carbon Transition, s.l.: Climate Policy Initative. · Stern, N., 2007. Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change. s.l.:Cambridge University Press.

|