|

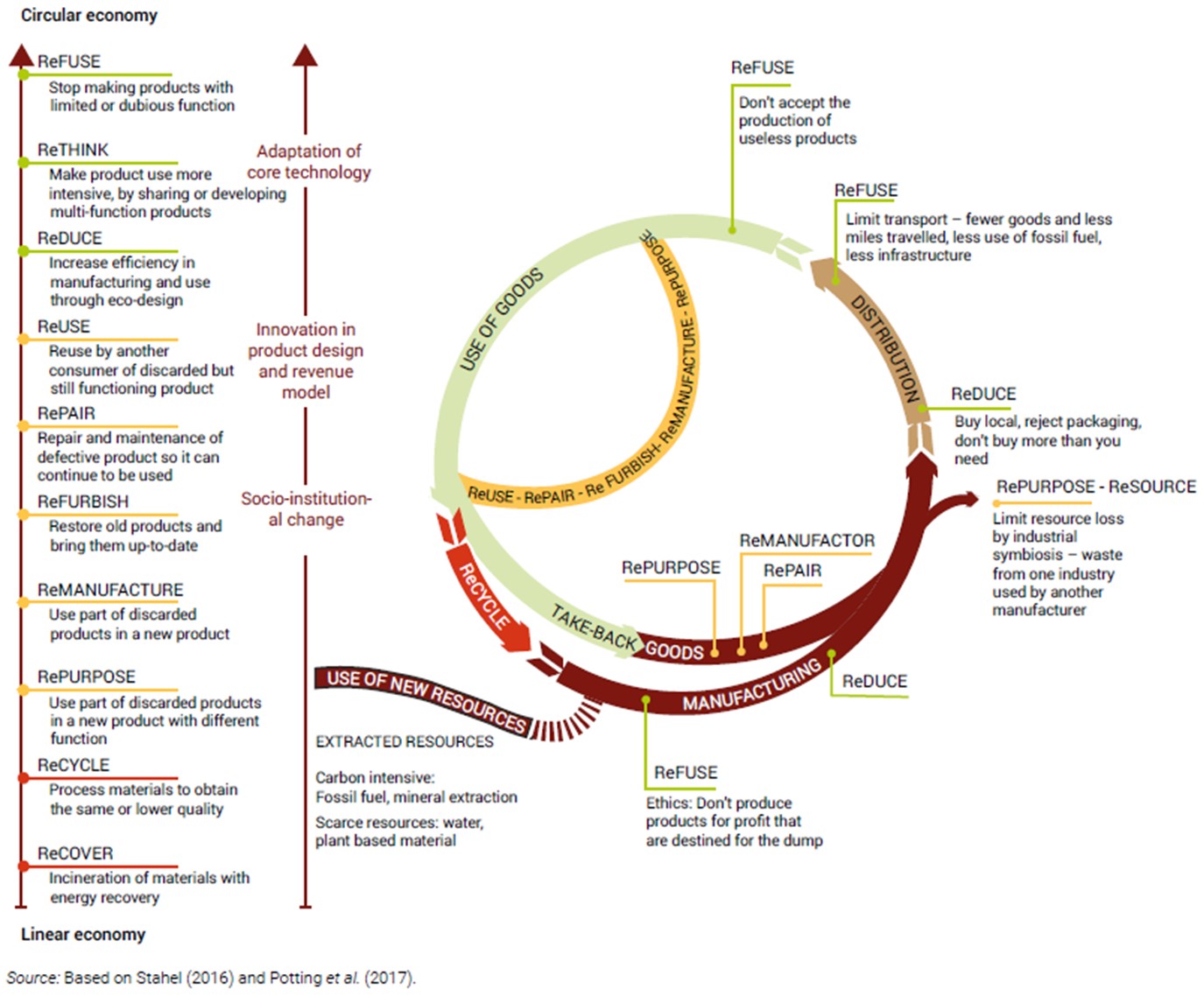

A circular economy is a systems approach to economic activity that aims to reduce the environmental impacts of production and consumption processes. While in its most basic applications in industrial ecology, it is primarily a waste management strategy. However, its larger objective is to drive larger systemic change by informing consumption behaviours to reduce the overall demand for products and services and minimise virgin resource extraction, thereby facilitating the decoupling of economic growth from its material footprint. In designing long-term policy strategies to meet the goals and targets of SDG 12 and promote sustainable consumption and production practices, it is critical to nudge consumer behaviours, both individual and institutional, by shifting priorities away towards the top of the 9R framework of the circular economy approach (refer to Figure 1) and looking at a more radical rethinking of consumer needs and wants, and new ways to meet them. As a thumb rule, environmental pressures reduce as one goes higher up the 9R hierarchy. This makes it crucial to aim at higher-order circularity strategies by redesigning consumption patterns, thus going beyond the myopic and primitive focus on recovering and recycling secondary resources and encouraging consumers to rethink their product choices, and reducing their overall consumption, while refusing unsustainable products.

Figure 1. 9R framework of the circular economy approach Besides the necessary improvements in product design and core technologies, policy frameworks and business models must facilitate systemic socio-institutional changes and shift fundamental consumer behaviour from being ‘consumers’ of resources to ‘users’. This can help meet aspirational user demands but at a lower environmental cost by developing sharing models and encouraging a culture of repair and reuse. These new models will need to be accompanied by behavioural strategies to increase the sociocultural acceptability of repurposed, refurbished, or recycled products, enhancing the availability of choice to meet consumer expectations at comparable price points, and enhancing trust in new solutions and avoiding greenwashing by improving the availability of reliable product information.

India’s flagship policy

initiative ‘LiFE - Lifestyle for the Environment’ is a welcome step in

this direction. While the nuances of its guiding principles and

strategies may continue to evolve, the unprecedented focus on informing

demand-side patterns plays a key role. The challenge is operationalising

the LiFE mission through intelligent policy design with a long-term

vision that can effectively embed circularity into consumption

behaviours and avoid the long-term socio-technical lock-in of

unsustainable solutions.

A useful approach can be designing ‘policy packages’ that restrict unsustainable practices and promote future good practices while continuously responding to changing baselines. A ‘framework legislation’ approach can also be helpful, such as the EU Circular Economy Action Plan, which does not set specific measures but establishes processes and mechanisms that enable their future adoption. These can also effectively lay down frameworks or coordination mechanisms between different government departments and agencies to contribute to the same vision through improved policy architecture. For instance, in India, implementation strategies for LiFE must allow for and proactively encourage the inclusion of various ministries, including environment, industry, consumer affairs, education, skill development, urban affairs, finance, and others. It is clear that nudging individual behaviours to drive sustainable consumption is not an easy feat; however, it is an essential prerequisite to mainstreaming circularity. To do this, policy strategies must understand and incorporate the finer nuances of human choice-making and their sociocultural drivers while allowing for adaptive pathways that can adequately respond to evolving external environments. References Garrett, Elizabeth. 2004. ‘The purposes of framework legislation’. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.504783. United Nations Environment Programme. 2015. ‘Sustainable Consumption and Production Global edition: A Handbook for Policymakers’. Available at https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=1951&menu=35, [accessed on 25 September 2021]. United Nations Environment Programme. 2021. ‘Catalysing Science-based Policy Action on Sustainable Consumption and Production – The value-chain approach and its application to food, construction and textiles’. Available at: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/catalysing-science-based-policy-action-sustainable-consumption-and-production ,[accessed on 25 September 2021].

Mohak Gupta |