|

India is among the youngest countries in the world, with 67% of its population of 1400 million in the working age group. By 2030, another 100 million people are expected to seek gainful employment in the country [1]. Thus, India is witnessing one of the highest demographic dividends in the world and has an unprecedented opportunity to develop and grow economically, as reflected in the annual GDP increase from 6% to 8% between 2010 and 2020. And yet, India’s rapid and consistent economic growth has failed to translate into job opportunities for its 48 million unemployed citizens [2], making jobless growth one of the most pressing concerns for the country. Over and above that, tens of millions more are caught in a web of disguised unemployment, underemployment, or tenuous and undignified work. Over the years, grassroots entrepreneurship has emerged as a response to the rapidly changing paradigm of employment in India and an avenue for local, opportunity-driven, and dignified employment, especially for women and youth who have been the most vulnerable to the changes in the macroeconomy shocks. The evolution of these enterprises has, however, been constrained by a complex set of challenges, which includes access to critical resources and gender and societal barriers, among many other factors that hinder the growth of entrepreneurship. Moreover, the growth in entrepreneurial activity in India has been far from uniform. On the one hand, the country is shining as an example of entrepreneurship, with the growth rate of enterprise set-up being almost 10% annually. On the other hand, many young individuals and women aspiring to become entrepreneurs, especially in rural communities, are being left behind. While 83% [3] of the Indian workforce aspires to become entrepreneurs, only 5% [4] are able to cross the threshold of establishing businesses; one of the lowest rates in the world. Several attempts have been made by enterprise development agencies to bridge the existing gaps, but the lack of collaboration and deep silos that exist among the available infrastructure, government programmes, and support services have not been adequately addressed. Dependence on government schemes and affiliated service providers perpetuates one-way, top-down flows and relationships in enterprise development projects and programmes. Civil society initiatives offer more comprehensive support but are negligible in terms of their impact. The Emergence of Entrepreneurial Ecosystem There is a need to build a conducive social and economic environment in rural India, more commonly known as an ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’. The aim of such an ecosystem is to enable aspiring individuals to take up entrepreneurship opportunities. This ecosystem comprises actors such as government institutions, grassroots implementation agencies, private entities, innovators, and businesses, having different attributes, decision principles, and beliefs that bring together specialised yet complementary resources for orchestrated efforts to make setting up and running successful enterprises easier. They are responsible for building bridges between a large number of entrepreneurs active at the microlevel and influential, resource-rich macro-level agencies. This necessitates the need to build a new kind of shared ‘institutional infrastructure’ that can understand local socio-economic imperatives, share relevant insights, and support multi-stakeholder action to co-create strategies for long-term resilience in the economy along with an intense focus on empowerment, livelihood security, and entrepreneurship. Through initiatives led by Development Alternatives such as the Work4Progress programme, human-centred tools and prototypes have been co-created with rural communities to 'poke' the ecosystem into removing barriers to entrepreneurship in regions of their operation. One such prototype is the District Entrepreneurship Coalition (DEC). It is designed with the objective to establish linkages amongst actors, working in the space of entrepreneurship, and channelise and optimise the efforts and resources of multiple stakeholders towards the common goal of job creation through enterprise development. The key stakeholders of this initiative include government agencies such as the District Industries Centre, National Rural Livelihood Mission, Agriculture Department, Department of Horticulture; financial institutes including the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, banks, NGOs, microfinance institutions; market aggregators; training institutes including Rural Self Employment Training Institutes; universities; and, most importantly, entrepreneurs. A Pathway for Two-way Communication

The transitions in stakeholder behaviour that emerged in Mirzapur took years of manoeuvring for it to become a means for two-way communication and eventually take the shape of a ‘model coalition’, with 25 stakeholders forming the core committee. The resultant ecosystem has enabled the establishment of 909 enterprises in four years, which lead to the creation of 3418 jobs across a small area of only 50 villages in Mirzapur. Additionally, the interconnectedness between different actors of the ecosystem led to a reduction in the average time to set up an enterprise from three months to just three weeks, ergo significantly boosting the rate of setting up enterprises. Advantages of Systemic Prototypes

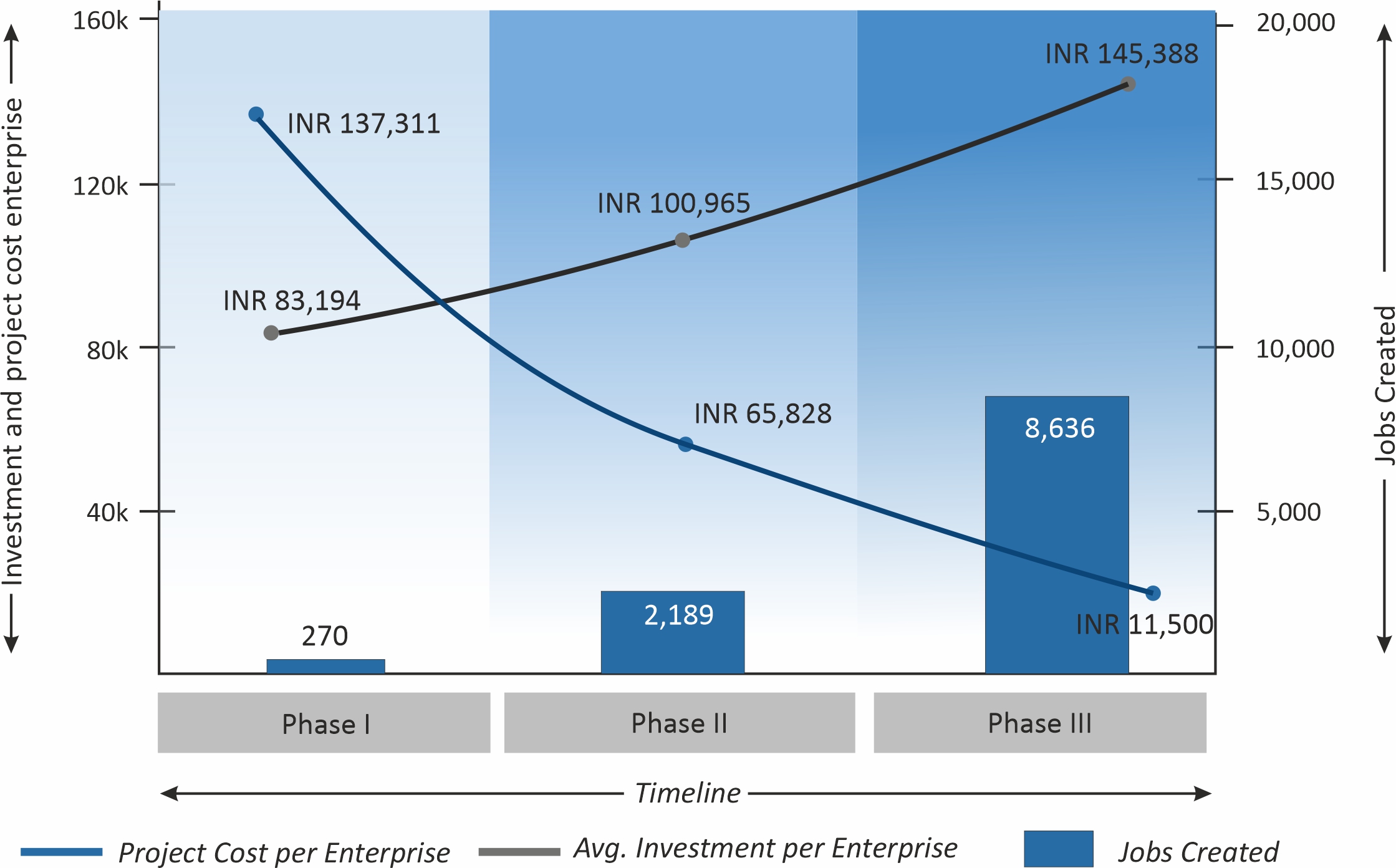

Similar breakthroughs have been seen in enhanced access to business information and market exposure. Based on the survey by Development Intelligence Unit (DIU) and Development Alternatives in 2022, only 8.1% of 2061 entrepreneurs surveyed reported access to business information. Over the last five years, the DEC platform has attained a status of an information hub by bringing together information from more than 15 sectors on the table. It has also enabled entrepreneurs to expand their reach way beyond the boundaries of their villages through trade fairs, exports, and e-commerce platforms. The effectiveness of the DEC prototype compares favourably with linear top-down enterprise development programmes, which, more often than not, lack comprehensiveness in response to a potential entrepreneur’s needs, creating major gaps within institutional support structures and mechanisms for entrepreneurship. The results of the ‘ecosystem-building’ approach are evident in a 90% reduction in the cost of setting up each enterprise to INR 11,500 for external support agencies such as Development Alternatives in the last five years. It also offers an alternative to the aggregator approach in which, most commonly, a social entrepreneur or government agency provides ‘market linkages’, thus creating a long-term dependency on the aggregator. As an enabler of systemic change, the DEC prototype underlines the need for innovation in ‘collaborative institutional ecosystems’ to bring about shifts in the behaviour exhibited by various actors, as a means for building synergies between initiatives, stakeholders, and entrepreneurs themselves. It is now ready for replication and has been introduced to stakeholders by Development Alternatives and Transforming Rural India Foundation (TRIF) as part of the Uttar Pradesh State Rural Livelihoods Mission’s initiatives in three blocks of Basti, Bahraich, and Lakhimpur districts. References 1. Bhargava, Y. 2022. India's GDP can grow to $40 trillion if working-age population gets employment: CII Report. The Hindu. 2. CMIE. n.d. Unemployment in India - A Statistical Profile. 3. Randstad Holding. 2017. Global Report Randstad Workmonitor wave 2, 2017 nv. Details available at Randstad Workmonitor Q2 - June 2017, last accessed on 3 January 2023. 4. Shukla, S., N. S. C. S. Chatwal, P. Bharti, A. K. D. K. Dwivedi, and V. Shashtri. (n.d.). (rep.). Global Entrepreneurship Report 2018/2019. London; Routledge .

Shrashtant Patara

Supriya Shukla

Muskan Chawla |

What started as informal meetings in 2017 to facilitate pathways of

cooperation eventually grew into a robust platform in the Mirzapur

district of Uttar Pradesh by the end of 2022. Development Alternatives,

along with its implementation partners SVSS and MDSS, facilitated the

initial coalition meetings to take the conversations beyond

individualistic challenges, journeys, projects, and schemes, and foster

a sense of collaboration among the members. Over the next two years, the

discourse changed from its initial suggestive or advisory tone about

what an entrepreneurship development agency such as Development

Alternatives should do, to action-oriented discussions about the role

that coalition members should play, collaboratively, in making

entrepreneurship more accessible in Mirzapur.

What started as informal meetings in 2017 to facilitate pathways of

cooperation eventually grew into a robust platform in the Mirzapur

district of Uttar Pradesh by the end of 2022. Development Alternatives,

along with its implementation partners SVSS and MDSS, facilitated the

initial coalition meetings to take the conversations beyond

individualistic challenges, journeys, projects, and schemes, and foster

a sense of collaboration among the members. Over the next two years, the

discourse changed from its initial suggestive or advisory tone about

what an entrepreneurship development agency such as Development

Alternatives should do, to action-oriented discussions about the role

that coalition members should play, collaboratively, in making

entrepreneurship more accessible in Mirzapur.  Systemic prototypes such as the DEC have

proved to be a breakthrough for influencing behaviour and driving

policy-level shifts. Some of the most significant changes have been on

account of improved access to credit, information, market exposure,

and other critical inputs for entrepreneurial success. With multiple

microfinance institutions, non-banking financial companies, and banks

providing timely credit support at competitive interest rates, the

negotiating power has shifted into the hands of entrepreneurs. They now

have a plethora of choices to make use of credit support. The changing

credit landscape has led to a five-fold increase in access to credit

support in the last three years across seven districts, with credit

worth INR 40 million leveraged by 1000+ entrepreneurs. The solidarity

developed among local financial stakeholders has also influenced change

in the norms of microfinance institutions and mainstream banks, either

in the form of reducing interest rates or in increasing the loan

duration.

Systemic prototypes such as the DEC have

proved to be a breakthrough for influencing behaviour and driving

policy-level shifts. Some of the most significant changes have been on

account of improved access to credit, information, market exposure,

and other critical inputs for entrepreneurial success. With multiple

microfinance institutions, non-banking financial companies, and banks

providing timely credit support at competitive interest rates, the

negotiating power has shifted into the hands of entrepreneurs. They now

have a plethora of choices to make use of credit support. The changing

credit landscape has led to a five-fold increase in access to credit

support in the last three years across seven districts, with credit

worth INR 40 million leveraged by 1000+ entrepreneurs. The solidarity

developed among local financial stakeholders has also influenced change

in the norms of microfinance institutions and mainstream banks, either

in the form of reducing interest rates or in increasing the loan

duration.