|

While India is at the cusp of an economic shift driven by innovation, the narrative is incomplete without taking into consideration the substantial demographic share as 65% of the country’s population is under the age of 35 years [1]. As the majority of India’s population lives in rural areas, the country’s potential lies in its rural geographies and the younger population, especially women. Data from a survey undertaken by Development Intelligence Unit (DIU) and Development Alternatives indicate an emerging trend, whereby 44% of young adults aspire to become entrepreneurs. Moreover, a behavioural shift is evident as 9 out of 10 rural businesses are first-generation enterprises, an indication of a growth in risk-taking [2]. As per the study, one of the viable avenues where these energies can be galvanised is through Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME). These have been showing considerable growth [3] and are one of the largest job creators [4] in the country. MSME also provides an individual with the opportunity to contribute to the local economy and can possibly bridge the gaps in the immediate market, which is crucial when considering that we are at the summit of the shift from subsistence to aspirational consumption. In this regard, entrepreneurship has the potential to create jobs that are not only sustainable but also inclusive. Inclusivity is essential because only 21.2% of Indians in the workforce are skilled [5]. For the inclusive element to be operationalised, there needs to be a systemic shift towards inclusive entrepreneurship that would facilitate an aspirational population to sustain themselves. In essence, there needs to be a significant realignment for a robust local ecosystem that can identify and respond to the aforementioned barriers.

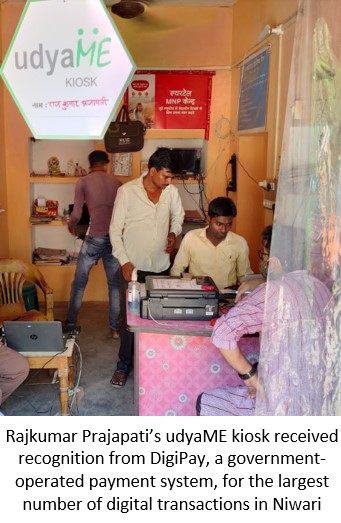

The first crucial step to reconciling deficiencies in this aspect is access to information. This is because there are discontinuities in knowledge and information between the amenities that are available to an individual, such as market linkages, potential credit facilities, and government schemes, which would help them set up an enterprise. The udyaME kiosk, in this sense, has been a game-changer as it provides real-time service to aspiring entrepreneurs on schemes, programmes, and networks that would benefit the individual. udyaME has served as a network of support for entrepreneurs and provided the necessary inceptive knowledge to start an enterprise. Rajkumar Prajapati, 29, is part of a peer network of over 10 udyaME kiosks and provides thousands of micro-entrepreneurs critical business services. Between September and December 2022 alone, he assisted seven people to access information required for setting up their businesses. From starting a small Common Service Centre to transforming it into an udyaME kiosk with 136 enterprise support services, he has effectively provided last-mile delivery of these services to up to 15 km of the village in the Niwari district of Bundelkhand.

However, for making entrepreneurship accessible to a larger population, many other factors have to be taken into consideration including gender, mobility, and finance, to mention a few. All these factors are embedded in the structural fabric of the economic catchment of a region, and the social structure in general. These factors intersect at certain points, but there is a concurrent factor that is prevalent throughout; it is gender. Whether that involves mobility, access, or even the predominant and inhibiting patriarchal culture, gender is the undercurrent that permeates the entire structure. Brave Spaces was conceived with that in mind and it serves in some respect as a starting point for women who aspire to venture into entrepreneurship through connections of solidarity with other women to be open about their dreams and aspirations, which, in many cases, is a rare accessibility.

References 1. National Statistical Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. 2022. Youth in India. Details available at https://mospi.gov.in/documents/213904/2007837//Youth%20in%20India%2020221656948055574.pdf/f93db380-dc68-e25c-e4bd-3042630a4aa7, last accessed on 31 January 2023 2. Development Intelligence Unit, Development Alternatives. 2022. Insights into Rural Entrepreneurship. Details available at https://www.jobswemake.org/pdf/Insights_into_Rural_Entrepreneurship_2022.pdf, last accessed on 31 January 2023 3. Mordor Intelligence. nd. India ICT Market - growth, trends, COVID-19 impact and forecasts (2023-2028). Details available at https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/india-ict-market, last accessed on 31 January 2023 4. Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. 2022. Annual Report 2021-2022. Details available at https://msme.gov.in/sites/default/files/MSMEENGLISHANNUALREPORT2021-22.pdf, last accessed on 31 January 2023

5. UNDP. 2020. Human Development Report. AGS,

United States. Details available at

https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdr2020pdf.pdf,

last accessed on 31 January 2023

Debasis Ray

Dabormaďan Jude |

In this context, Development Alternatives champions local

micro-enterprises as drivers of economic growth. To nurture these

micro-enterprises, there is a need for a holistic purview as well as

infrastructural/systemic change at local levels. Systemic prototypes

developed by Development Alternatives attempt to address the issues that

serve as an impediment to the growth of entrepreneurship. It has

developed programmes through the methods of deep listening and

co-creating with the communities. The programmes are prototypes that

remove barriers to entrepreneurship in regions of their operation and

primarily designed to nurture constructive communities, unleash

entrepreneurial energies, and empower micro-enterprises through a robust

enterprise ecosystem.

In this context, Development Alternatives champions local

micro-enterprises as drivers of economic growth. To nurture these

micro-enterprises, there is a need for a holistic purview as well as

infrastructural/systemic change at local levels. Systemic prototypes

developed by Development Alternatives attempt to address the issues that

serve as an impediment to the growth of entrepreneurship. It has

developed programmes through the methods of deep listening and

co-creating with the communities. The programmes are prototypes that

remove barriers to entrepreneurship in regions of their operation and

primarily designed to nurture constructive communities, unleash

entrepreneurial energies, and empower micro-enterprises through a robust

enterprise ecosystem. To channel these flows of knowledge at a

meso level, a district-level platform called DEC (District

Entrepreneurship Coalition) seeks to address the problem of

organisations and groups working in silos, whereby various stakeholders

can come together to co-create nonlinear solutions to local challenges

through collaborative action. They can align and share knowledge, practices, and ideas

as they work towards a common goal. Jauhar Ansari, 32, from Mirzapur,

returned to his village in 2016 after working at garment firms across

North India. Within a year, he established a garment manufacturing

business and his unit, today, has 24 full-time employees from nearby

communities. During the pandemic, Jauhar ensured that none of his

workers were laid off. He started employing local youth seasonally and became the

voice for creating market breakthroughs with his continuous efforts to

unlock market opportunities through coalitions. Through his enterprise, Jauhar is defying the common narrative that only large corporations can

be job creators.

To channel these flows of knowledge at a

meso level, a district-level platform called DEC (District

Entrepreneurship Coalition) seeks to address the problem of

organisations and groups working in silos, whereby various stakeholders

can come together to co-create nonlinear solutions to local challenges

through collaborative action. They can align and share knowledge, practices, and ideas

as they work towards a common goal. Jauhar Ansari, 32, from Mirzapur,

returned to his village in 2016 after working at garment firms across

North India. Within a year, he established a garment manufacturing

business and his unit, today, has 24 full-time employees from nearby

communities. During the pandemic, Jauhar ensured that none of his

workers were laid off. He started employing local youth seasonally and became the

voice for creating market breakthroughs with his continuous efforts to

unlock market opportunities through coalitions. Through his enterprise, Jauhar is defying the common narrative that only large corporations can

be job creators.