|

Overview Climate change has become the inevitable reality of today’s world and its impact on the global agriculture sector is manifold. According to the World Bank [1], the agriculture sector currently contributes 19-29% to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and without any action in this direction, this percentage would invariably increase and further pose threat to the planet’s environs. Such a scenario makes India, an agrarian country, susceptible to considerable environmental impacts due to climate change. As per India’s Third Biennial Update Report 2021 [2], submitted by the Government of India to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Indian agriculture sector contributed 14% of the total GHG emissions in 2016. In India, the maximum agricultural GHG is emitted at the primary production stage and directly generated through the production and use of agricultural inputs, soil disturbance, and residue management to increase crop yield and harvests. In this regard, Indian agricultural policies or initiatives often act as a panacea to mitigate climate change-related disasters. In this article, we will discuss one of the most important agricultural policies, the minimum support price policy, and its relationship with climate change. Minimum Support Price

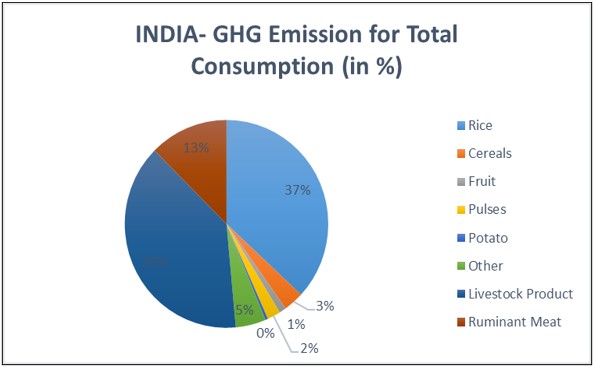

Although this policy was started by the Government of India in 1966-67 to help farmers incentivise in growing a selected variety of crops, it has resulted in land degradation, excessive pressure on crops and land, etc. The Commission for Agricultural Crops and Prices1 (CACP) issues minimum support price for 23 crops pan-India, out of which 5 crops, i.e., rice, wheat, coconut, sugarcane, and pulses, emit the highest percentage of GHG emissions. The following are the impact of minimum support price on climate change:

Figure 2: Distribution of GHG emissions from

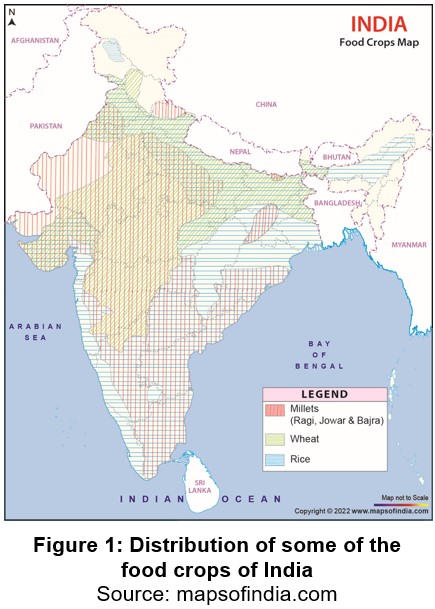

agricultural production in the Indian diet Recommendations India has a plethora of indigenous climate-resilient strategies that need to be acknowledged and promoted to avoid environmental crises. For effective implementation of agricultural policies, PPP (public-private partnership) model could be used and climate experts, policymakers, local communities, etc. engaged in climate change-related policies. For the states suffering from minimum support price-related environmental crisis, heavy investments in soil reclamation should be done. Another important step is a precise and planned fertiliser strategy, especially for Punjab, Haryana, and Western Uttar Pradesh farmers. Moreover, crops other than wheat and rice should be scaled up to a national level following strong institutional reforms that cater to the rice and wheat production system. Even after so many years post the implementation of minimum support price, there is still a lot of ambiguity related to it. Thus open digital access to real-time mapping and tracking of agricultural policies and their database are required. The following are the suggestions for less emission-intensive rice and wheat production:

References World Bank. 2021. Climate Smart Agriculture. Details available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climate-smart-agriculture, last accessed on 17 January 2023. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India. 2021. India: Third Biennial Update Report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Details available at https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/INDIA_%20BUR-3_20.02.2021_High.pdf, last accessed on 17 January 2023. Press Information Bureau. 2022. Press Information Bureau. Details available at https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1868579, last accessed on 8 December 2022. Endnote 1Read more at https://cacp.dacnet.nic.in/

Kanika Kalia |

Minimum

support price is a ‘minimum price’ for any crop that the government

considers as remunerative for farmers and, hence, deserves ‘support’. It

is the price/rate that the government has to pay to procure a particular

crop.

Minimum

support price is a ‘minimum price’ for any crop that the government

considers as remunerative for farmers and, hence, deserves ‘support’. It

is the price/rate that the government has to pay to procure a particular

crop.