|

The

2017-18 Economic Survey had cautioned that climate change might reduce

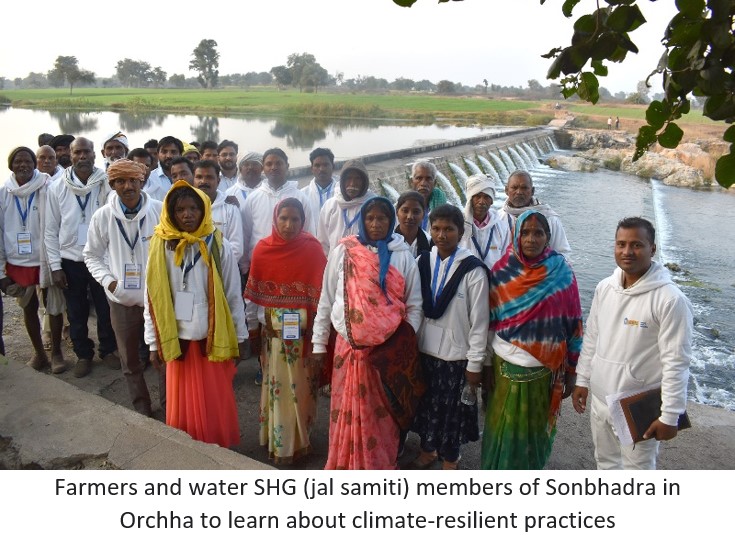

India’s annual agriculture income in the To address the adverse effects of climate change, we must develop adaption and mitigation options, i.e., ‘climate-resilient’ practices. This requires action on a war footing to create infrastructure in terms of both human resources and state-of-the-art physical facilities for collecting, collating, and updating climatic data. These are essential prerequisites for modelling and forecasting the impact of climate change on agriculture. Also, the strategies must be built upon the current knowledge about climatic, ecological, and economic systems’ dynamics. At the same time, it is important for us that this knowledge percolates even to the remotest village of our country. Until and unless we have masses understanding of the importance and urgency of adapting to ‘climate-resilient’ practices, we will not be able to achieve the much-required shift. Based on the principle that knowledge must reach even the remotest village in the country, Development Alternatives’ flagship programme, Shubhkal takes the knowledge regarding climate-resilient practices to the remotest regions of drought-prone Bundelkhand. The programme is about building a mass movement, where we are creating climate-change warriors or ‘Shubhkal leaders’ who not only practice the ‘climate-resilient’ practices but also create awareness about it. For the farmers, soil health is equally important as their health. Short-term gains are ignored for long-term climatic health options. Climate change is happening now and for us to be ‘happening’, we need to adapt and adopt wisely. Until and unless the masses understand the importance and urgency to adopt ‘climate-resilient’ practices, the much-required shift will not be possible. References https://indbiz.gov.in/one-of-the-youngest-populations-in-the-world-indias-most-valuable-asset/

Government of India. 2018. Climate, climate

change, and agriculture. Economic Survey 2017-18, Volume 1. Details

available at:

https://mofapp.nic.in/economicsurvey/economicsurvey/pdf/082-101_Chapter_06_ENGLISH_Vol_01_2017-18.pdf,

last accessed on 16 December, 2022

Jyoti Sharma |

range of 15% to 18% and up to

20%-25% for unirrigated areas. Even now we can see the effects of

climate change aggravating our problems as an agro-producer nation. As

per a 2022 World Bank report, the country may soon become one of the

first places in the world to experience heat waves that can break the

human survivability limit. Further, changes in the weather pattern and

exposure to harsh climatic conditions will especially impact smallholder

agricultural workers. It will create food shortages and nutrient

deficiencies in the nation due to inadequate intake of healthy food,

which will make us vulnerable to new-age health disorders. This was

evident as per the Global Hunger Index 2020 in which India ranked 94

among 107 countries despite being an agrarian country. This indicates

the country’s limited food is available for its growing workforce, which

has one of the youngest nations in terms of its demographic dividend. In

this scenario, an important question arises: does the country have

enough resources to ensure food security in the country? More than a

decade ago, in its Fifth Assessment Report, the Inter-governmental Panel

on Climate Change (IPCC) had warned of the dire consequences of climate

change on human health, settlements, and natural resources, if no

constructive measures are taken to mitigate the effects of global

warming. If we do not wake up even now to the problem, then

agriculture-related livelihoods, which engage 58% of India’s population,

will suffer.

range of 15% to 18% and up to

20%-25% for unirrigated areas. Even now we can see the effects of

climate change aggravating our problems as an agro-producer nation. As

per a 2022 World Bank report, the country may soon become one of the

first places in the world to experience heat waves that can break the

human survivability limit. Further, changes in the weather pattern and

exposure to harsh climatic conditions will especially impact smallholder

agricultural workers. It will create food shortages and nutrient

deficiencies in the nation due to inadequate intake of healthy food,

which will make us vulnerable to new-age health disorders. This was

evident as per the Global Hunger Index 2020 in which India ranked 94

among 107 countries despite being an agrarian country. This indicates

the country’s limited food is available for its growing workforce, which

has one of the youngest nations in terms of its demographic dividend. In

this scenario, an important question arises: does the country have

enough resources to ensure food security in the country? More than a

decade ago, in its Fifth Assessment Report, the Inter-governmental Panel

on Climate Change (IPCC) had warned of the dire consequences of climate

change on human health, settlements, and natural resources, if no

constructive measures are taken to mitigate the effects of global

warming. If we do not wake up even now to the problem, then

agriculture-related livelihoods, which engage 58% of India’s population,

will suffer.