|

An Ecosystem Approach

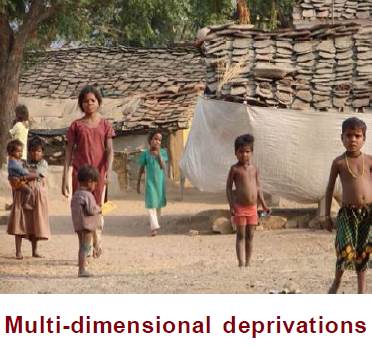

W ill the post-2015 development agenda end poverty in India? It took over six decades to bring poverty levels in our country down from roughly 60% to 30% (Akbar, 2014). At this rate, it should take another six decades to reduce poverty to zero. The sustainable development goals (SDGs), however, endeavour to do this in 15 years. Is this practically possible? If we do a SWOT analysis, the opportunities are that circumstances today are very different from 60 years ago. The Indian economy’s growth rate, pace of technological and medical advancement and magnitude of public development spending today are exceptional as compared to any other time in history (Rao, 2013). The threats however are that India will soon be the most populous nation in the world. Its economic growth in recent years has not created enough jobs. Most of its graduates have minimal employable skills, possibly foreshadowing the conversion of India’s much-anticipated demographic dividend into its demographic disaster.Arguing for a multi-dimensional approach to poverty, this article explores two policy issues: countervailing interventions and interventions without foresight and concludes with recommendations for an ecosystem approach. Poverty as Capability Deprivation Amartya Sen’s capability approach views poverty as the systematic deprivation of the basic capability of individuals to live the kind of lives they have reason to value (Sarshar, 2010). Going beyond income deprivation, it recognises other forms of deprivations which having an income alone may not alleviate. Multi-dimensional poverty measures such as the Alkire Foster measure (OPHI, n.d.) provide a broader measure of deprivation than income poverty measures used in India. India’s Socio-Economic Caste Census 2011 looks at seven kinds of deprivations, concluding that almost half of India’s rural households suffer from at least one of these deprivations. Such data may be used to target specific deprivations (Rangarajan & Dev, 2015). Ending multi-dimensional poverty requires achieving

all SDGs including Go The achievement of each SDG clearly benefits the poor. However, the pathways chosen to achieve certain SDGs may also work against the poor, not allowing them to fully enjoy the benefits of development. Countervailing Interventions A common theme of the SDGs is sustainability, visible for example in the target to achieve sustainable food production systems in Goal 2. This has direct implications for rural India which is predominantly engaged in agriculture and particularly the rural poor. India’s fertiliser and power subsidies incentivise farmers to grow resource-intensive crops. Fertiliser and water overuse has caused soil degradation and rapid drops in groundwater levels. Interestingly, a Greenpeace India report (Roy, et al., 2009) argues that while fertilisers did raise productivity in the early years of the Green Revolution, they may now be reducing productivity in many areas due to soil degradation. So, should the subsidy be removed to achieve Goal 2? An IIM-Ahmedabad study (Sharma, 2012) states that removing the fertiliser subsidy may make farming unprofitable in many states, leaving tens of millions of poor farmers without employment. Policies aimed at achieving Goal 2 should be cautious of these effects. Any move to remove these subsidies must be complemented by other schemes to improve farm productivity sustainably. Incentivising private investment in improving the efficiency of traditional practices or discovering new green practices may be a useful policy pathway, as it does not require direct subsidies and may even be cost effective. Agriculture being prone to weather fluctuations, drought-resistant or salt tolerant crops are often promoted for adaptation. However, many drought-resistant crops have low returns. Investing in agricultural diversification may be more responsive to the needs of both agricultural resilience and poverty reduction. Without careful weighing of different alternatives for adaptation for the rural poor, one risks trapping the poor in low-value livelihoods (Dercon, 2012). Goal 7 emphasises renewable energy and Goal 9 retrofitting industries for sustainability. Capital costs are currently higher for renewable energy than for conventional energy. To spur a transition, the government may have to subsidise green technologies, so that gradually with research and development, the scope for ‘learning by doing’ and achieving economies of scale; the costs of green technologies will reduce to the levels of non-green alternatives. However, with India’s numerous subsidies already spinning out of control, additional subsidies may divert funds away from pro-poor sectors such as healthcare and education. This dilutes the poor’s benefits from green interventions as it leaves them less capable to take advantage of new green jobs. The policy scenario in India has historically followed the path of promoting industrialisation. Land acquisition may be required to be used to achieve Goals 9 (promoting industry) and 11 (urban infrastructure and services). However, land acquisition sometimes leaves the poor worse off. Compensation given to land-owners is often inadequate. The bulk of the rural poor are landless or small/marginal farmers who lose not only whatever little land they had but also the opportunity to work on others’ land and grains received as remuneration. They are often unable to find alternative employment due to low levels of human capital. Such indirect outcomes of land acquisition are rarely compensated for. Industrialisation is said to create jobs. However, while 285 million people in the 15-29 age group entered the Indian workforce from 2009-10 to 2011-12, the jobless nature of growth added only 15 million jobs between 2004-05 and 2011-12 (Niazi, et al., 2014). Moreover, even if industrialisation was labour-intensive, it would not benefit the poor if the jobs created favour skilled labour, as the poor tend to be poorly skilled. Goals 6, 14 and 15 call for the protection and restoration of water-related, marine and terrestrial ecosystems respectively. Policies enforcing these goals may take the form of usage restrictions on forests and other natural resources on which the rural poor depend for their basic needs and livelihood. The affluent and those with political clout often find ways to bypass regulations, while the poor suffer the brunt of limited access as well as long-term repercussions of unsustainable use. Moreover, protecting areas has an opportunity cost: the intrinsic value of the resource as well as livelihoods lost and incomes foregone due to restriction. It is rare that the poor are adequately compensated for these costs. If that continues to be the case, achieving these SDGs may exacerbate poverty and inequality. Interventions without Foresight Goal 5 calls for gender equality. Policies addressing gender inequality in India often neglect the phenomenon’s complexity and as a result, sometimes push women into tight corners. Consider legal provisions for women’s right to inheritance. The policy has led many women to be harassed by their in-laws to demand their share of inheritance from their natal family. The share subsequently given to women is never truly theirs as in the Indian cultural set-up the ‘strings’ are in the hands of the husband and in-laws. Compounding the problem further, women lose face in their natal families due to deep cultural biases against women’s right to inheritance, so much so that they may even be refused support from their natal families in crisis situations. Poor women particularly are left worse off in such situations as they rarely have the capability to leave and live independently. Policies should be sensitive to such implications and also dilute harmful or unjust socio-cultural conventions; otherwise they may do more harm than good. Recognising Linkages India may learn from Ghana’s approach to removing fossil-fuel subsidies in 2005 exemplifying a multi-dimensional poverty approach. The government offset the price rise by eliminating fees for state primary and secondary schools, increasing investment in public bus transport with a price ceiling on fares, increasing funding for rural healthcare, increasing the minimum wage and investing in rural electrification. These wider compensatory measures helped tackle deeper deprivations of education, mobility, healthcare, wages and energy access (Raworth, et al., 2014). Without a multi-dimensional approach, the SDGs may aggravate the very problems they are looking to solve. Policies must recognise the complex linkages among SDGs, multi-dimensional nature of poverty as well as local socio-cultural contexts. Narrowly aiming to achieve a specific SDG without evaluating consequences for poverty reduction may create counterproductive outcomes. q

Peer Reviewed by References • Akbar, M., 2014. India’s public planners couldn’t end poverty, but its private sector can. [Online]•

Available at:

http://blogs.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/thesiegewithin/indias-public-planners-couldnt-end-poverty-but-its-private-sector-can/ • Dercon, S., 2012. Is green growth good for the poor?, s.l.: Policy Research Working Paper Series 6231, The World Bank. • Niazi, Z. et al., 2014. Lessons for India’s Transition to a Greener Economy: Inputs to the Global Transition Report, New Delhi: Development Alternatives. • OPHI, n.d. How to apply the Alkire Foster method: 12 Steps to a multidimensional poverty measure. [Online] •

Available at:

http://www.ophi.org.uk/research/multidimensional-poverty/how-to-apply-alkire-foster/ • Rangarajan, C. & Dev, S. M., 2015. The measure of poverty. [Online] •

Available at:

http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/the-measure-of-poverty/2/ • Rao, K., 2013. India’s poverty level falls to record 22%: Planning Commission. [Online] •

Available at:

http://www.livemint.com/Politics/1QvbdGnGySHo7WRq1NBFNL/Poverty-rate-down-to-22-Plan-panel.html • Raworth, K., Wykes, S. & Bass, S., 2014. Securing social justice in green economies: A review and ten considerations for policymakers, s.l.: International Institute for Environment and Development. • Roy, B. C., Chattopadhyay, G. N. & Tirado, R., 2009. Subsidising Food Crisis: Synthetic fertilisers lead to poor soil and less food. Bangalore: Greenpeace India. • Sarshar, M., 2010. Amartya Sen's Theory of Poverty, Delhi: National Law University. • Sharma, V. P., 2012. Dismantling Fertilizer Subsidies in India: Some Issues and Concerns for Farm Sector Growth, Ahmedabad: Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. •

The Hindu, 2015. Over 3,000 farmer suicides

in the last 3 years. [Online] |

al

1 i.e. ‘End poverty in all its forms everywhere’. Addressing hunger

(Goal 2), healthcare (Goal 3), education (Goal 4) and drinking water and

sanitation (Goal 6) issues enables good physical and mental health for

the poor. The poor benefit from energy access (Goal 7), full employment

and decent jobs (Goal 8) and sustainable industry (Goal 9) as these

initiatives create jobs and incomes. Sustainable consumption and

production (Goal 12), combating climate change (Goal 13) and protection

of marine and terrestrial ecosystems (Goals 14 and 15) help restore

natural resources and sustain the rural poor’s incomes, as a majority of

the poor people depend on natural resources for sustaining their

livelihoods.

al

1 i.e. ‘End poverty in all its forms everywhere’. Addressing hunger

(Goal 2), healthcare (Goal 3), education (Goal 4) and drinking water and

sanitation (Goal 6) issues enables good physical and mental health for

the poor. The poor benefit from energy access (Goal 7), full employment

and decent jobs (Goal 8) and sustainable industry (Goal 9) as these

initiatives create jobs and incomes. Sustainable consumption and

production (Goal 12), combating climate change (Goal 13) and protection

of marine and terrestrial ecosystems (Goals 14 and 15) help restore

natural resources and sustain the rural poor’s incomes, as a majority of

the poor people depend on natural resources for sustaining their

livelihoods.