|

Ensuring Food Security for All:

Strategies and Options

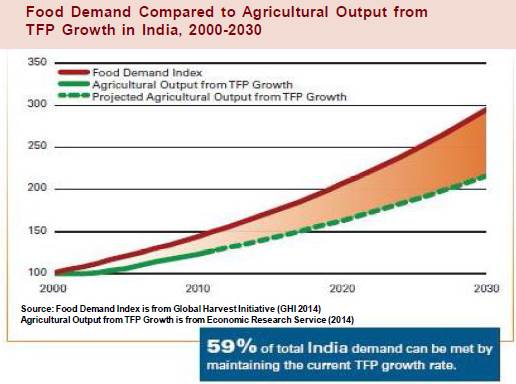

T he 2014

GAP Report estimates that India’s domestic production will only meet 59

percent of the country’s food demand by 2030 at the current growth rate

of Total Factor Productivity (Global Harvest Initiative, 2014). This

estimated food production gap raises serious concerns for India’s long

term food security. Despite tremendous growth, India is still home to a

quarter of all the undernourished population in the world (FAO, 2014).

It is of highest priority for India to ensure secure access to food for

all its citizens, now and for the future. This article explores various

options that India can pursue to ensure adequate food production to meet

the food demand of all it citizens by 2030.

Ensuring food security for all is one of the

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that India, along with 192 other

countries in the world, is in the process of commitment. This goal (SDG

2) aims to ‘End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition

and promote sustainable agri culture’. While we are exploring options

for India to ensure food security, it is important to remember that

apart from Goal 2 there are various other goals (Goal 1 - Poverty

Eradication, Goal 3 - Health and Well-being) which will be constrained

in their achievement due to food insecurity. India’s approach for Goal 6

(Universal Water Access and Sustainable Withdrawals of Water) and Goal 7

(Universal Access to Clean, Sustainable Energy) shall further impact its

food production systems as these are key inputs in agriculture. The

availability of resources of land, water and energy in agriculture will

compete with growing demands of the same from industrialisation (Goal 9)

and urbanisation (Goal 11). Goals on combating climate change (Goal 13),

conserving marine (Goal 14) and terrestrial ecosystems (Goal 15) shall

also impact India’s food production systems. At the same time,

strategies that India adopts in its food production systems shall also

impact achievement of these SDGs. culture’. While we are exploring options

for India to ensure food security, it is important to remember that

apart from Goal 2 there are various other goals (Goal 1 - Poverty

Eradication, Goal 3 - Health and Well-being) which will be constrained

in their achievement due to food insecurity. India’s approach for Goal 6

(Universal Water Access and Sustainable Withdrawals of Water) and Goal 7

(Universal Access to Clean, Sustainable Energy) shall further impact its

food production systems as these are key inputs in agriculture. The

availability of resources of land, water and energy in agriculture will

compete with growing demands of the same from industrialisation (Goal 9)

and urbanisation (Goal 11). Goals on combating climate change (Goal 13),

conserving marine (Goal 14) and terrestrial ecosystems (Goal 15) shall

also impact India’s food production systems. At the same time,

strategies that India adopts in its food production systems shall also

impact achievement of these SDGs.

India clearly needs to devise solutions in

agricultural production systems for ensuring food security keeping in

mind that these choices are extensively linked with other SDGs and thus

impact our socio-economic-environment systems. This article aims to

identify synergies in achieving India’s self-sufficiency of food for

food security (Goal 2) and other goals of SDGs that India can benefit

from while choosing its development pathways.

Expanding Land under Agriculture

At 157.35 million hectares, India holds the second

largest agricultural land globally (Kaul, 2015). Further expansion of

land dedicated to agriculture is one option for increasing production.

Land under agriculture has remained almost constant in the range of

140-143 million hectares since the 1990s (Government of India, 2014).

With rapid urbanisation (Swerts, Pumain, & Denis, 2014), increasing

energy demands and industrialisation which are land intensive

phenomenon, expanding land under agriculture without harming the

achievement of other SDGs looks rather difficult. The option of

converting forested land for agriculture use may adversely impact

environmental ecosystems (Goal 14, 15) and further add to the

uncertainties of climate change (Goal 13). However, National Remote

Sensing Agency estimates put culturable wastelands at 11.74 percent of

the total land area of the country 1.

This seems a possible opportunity to explore for expansion of

agriculture to wastelands suitable for cultivation.

Possibilities with Agriculture Intensification

India only has 35 percent of the area sown under

irrigation which provides more than 60 per cent of the food (Oza, 2007).

Water use in agriculture is around 80 percent of the total fresh water

use. This is despite the fact that only 35 percent of the agricultural

land is irrigated. Intensification of current agricultural practices may

cost heavily on our water resources. This represents a major challenge

for Goal 6 which has a target calling for ‘sustainable withdrawals of

water and protection of water-related ecosystems’. Intensifying water

use in agriculture shall lead to a trade-off with Goal 6 which may not

be sustainable in the long run.

Another study has estimated that about 70 per cent of

the growth in agricultural production can be attributed to increased

fertiliser application (Mondal, n.d.). However, introspection on results

from the multiple long-term fertiliser trials in rice-wheat systems have

revealed gradual deterioration of soil health and thus long-term

productivity due to overuse and imbalanced use of synthetic fertilisers

(Roy, Chattopadhyay, & Tirado , 2009). Increasing the use of fertilisers,

which are energy intensive in their production, shall pressurise the

energy systems in the usual scenario. Further, a 2013 study by the Food

Safety and Standards Authority of India showed how most common food

items contain banned pesticides in quantities that are several hundred

times over the permissible limit (Kowshik, 2015). It is noteworthy that

India has a potential of 650 million tonnes of rural and 160 lakh tonnes

of urban compost which is not fully utilised at present. The utilisation

of this potential can solve the twin problem of disposal of waste and

providing manure to the soil (Mondal, n.d.). Such interventions can

synergise the achievement of sustainable agriculture (Goal 2) and solid

waste management (Goal 11).

Raising Agricultural Productivity

For a country that has the second largest land under

agriculture, India produces far lower quantities of outputs than it

could. If India’s yield rates for rice and wheat were at China’s levels,

we could almost double our yields or halve the land used for the purpose

(Raghavan, nd). The average yield of rice in India is 2.3 tonne/ha as

against the global average of 4.374 tonne/ha. China is the largest

producer of rice with a per hectare yield of 6.5 tonne while countries

such as Australia (10.1 tonne) and US (7.5 tonne) lead the tally. The

report also says India has done better in wheat by achieving a yield

closer to the global average. It has recorded an average yield of 2.9

tonne per hectare as against the global benchmark of 3.0 tonne/ha.

However, it’s still far from countries like France (7.0 tonne) and China

(4.8 tonne) (Tiwari, 2012).

Low agricultural productivity is identified as one of

the primary causes of the low yield. When change in total factor

productivity was measured for Indian states, the improvements in

efficiency were observed to be low for most of the states and efficiency

decline is observed in several states implying huge gains in production

possible even with existing technology (Chaudhary, 2012). Increasing

efficiency of resource inputs in agriculture for enhancing food

production is identified as a critical step for food security. Further

in India, sustainable farming also includes the aspect of livelihood

farming considering that agriculture is the source of employment for

more than 60 percent of the population. Keeping this is mind, increasing

agricultural productivity through adopting efficient production systems

seems the most suitable approach to achieve food security with minimal

negative impacts on other SDGs.

Low agricultural productivity follows from a lot of

reasons. About 85% of the farmers in India are marginal or small farmers

with less than 2 hectares of land for farming. The average farm

household makes Rs 6,426 per month. Over half of all the agricultural

households are indebted. The average loan amount outstanding for a farm

household in India today is Rs. 47,000, which is an extremely heavy

burden (Shrinivasan, 2015). Possibilities of huge potential increase in

production even with existing technology will happen only by empowering

the small farmers. The first step in this direction should be to

increase the availability of investments and operating funds to farmers

for agriculture (Kumar & Mittal, 2006). An empirical study (Das,

Senapati, & John, 2009) indicates that financial inclusion of farmers in

the organised financial system boosts agriculture output.

Information and awareness amongst farmers on the

various implications of use of inputs and sustainable techniques of

agriculture also plays a critical role. Agricultural Extension Services

play a pivotal role in transferring good practices and green

technologies to farmers but it demands huge expansion in their scope and

reach. Numerous technologies and approaches for water and fertiliser

efficiency and matching seed technology with local climatic conditions

for diversification and multi-cropping have been developed in India. But

considering the potential for increasing agricultural yield in India,

there is still massive investment needed in agricultural research and

development. India currently spends only 0.76 percent of agricultural

GDP on public agricultural research. The commonly accepted target for

public spending on agricultural research and development for developing

countries is one percent of agricultural GDP (Global Harvest Initiative,

2014). This would mean that India needs to increase its research

spending from INR 5600 crores to approximately INR 14000 crores.

This article indicates that for India to achieve food

security without trading off achievement of other SDGs, there are

certain choices it will have to make. While expanding agriculture on

cultivable wastelands and replacing organic compost in place of

fertilisers for agriculture are some of them; the bulk of the potential

lies in investing in increasing agricultural productivity. Empowering

the farmers with investment opportunities and knowledge, along with

dedicated investments in agriculture research are identified as keys to

enhancing agricultural productivity.

q

Anshul S Bhamra

and Harshita Bisht

abhamra@devalt.org & hbisht@devalt.org

Peer Reviewed by

Aditi Kapoor,

Director - Policy Advocacy and Partnerships,

Alternative Futures

Endnote

1http://agridr.in/tnauEAgri/eagri50/FRST201/lec13.pdf

Bibliography

• Chaudhary, S.

(2012). TRENDS IN TOTAL FACTOR PRODUCTIVITY IN INDIAN AGRICULTURE:

Delhi School of Economics.

• Das, A., Senapati,

M., & John, J. (2009). Impact of Agricultural Credit on Agriculture

Production. Researve Bank of India

• FAO. (2011).

Energy-smart Food for People and Climate. FAO.

• FAO. (2014). The

State of Food Insecurity in the World. UN.

• Global Harvest

Initiative. (2014). Global Agricultural Productivity Report

• Government of India.

(2014). Pocket Book of Agricultural Statistics.

• Kaul, V. (2015).

India has enough land for farming but there are other bigger issues to

worry about. First Post.

• Kowshik, P. (2015,

April 7). Farm to Plate: How safe is your food? India Today.

• Kumar, P., & Mittal,

S. (2006). Agricultural Productivity Trends in India. Agricultural

Economics Research Review,

• Oza, A. (2007).

Irrigation and Water Resources. India Infrastructure Report.

• Raghavan, S. (nd).

Livemint. India’s agricultural yield suffers from low productivity.

• Roy, D.,

Chattopadhyay, P., & Tirado , D. (2009). Subsidizing Food Crisis:.

Greenpeace India.

• Shrinivasan, R.

(2015, June 27). Does it pay to be a farmer in India? The Hindu.

• Swerts, E., Pumain,

D., & Denis, E. (2014). The future of India’s urbanization. Futures,

Elsevier,, 43-52.

• Tiwari, R. (2012,

April 2). Indian crop yields less than global average. The Economic

Times.

Back to Contents |