|

The Urban Housing Policy

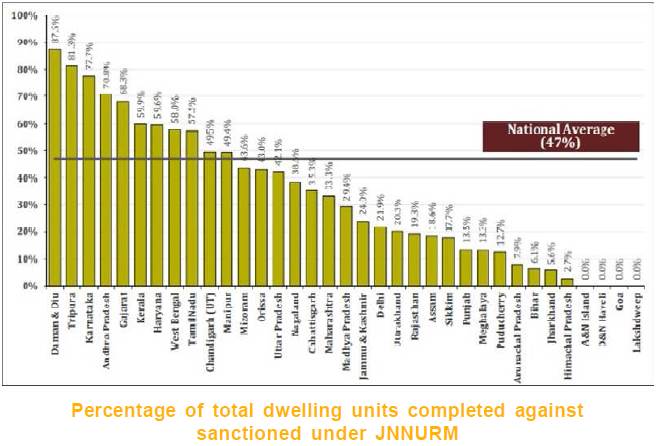

Debate Housing Programmes H ousing for All is a priority commitment for the Indian Government. The vision is that every family will have a pucca (permanent) house with water connection, toilet facilities, 24Χ7 electricity supply and access. The programme proposes to build 20 million affordable houses for the economically weaker section in metros, small towns and all urban areas of India by 2022. The budget has allocated Rs 22,407 crore for the housing and urban development sector for this fiscal year.Housing schemes have been planned and implemented before, without reaching the goal of eliminating homelessness. The Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), launched in 2005, was the first and biggest effort in the post-independence history of India to comprehensively address urban development. The scheme ran from 2005 to 2014, after being extended by two years for the completion of delayed projects. In 2012, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation (HUPA) pegged the housing shortage at 18.78 million units, with 96% of this demand in the affordable housing space. With the gap expected to grow to 38 million units by 2030 (MGI, 2010), the new target still falls short of eliminating homelessness. Thus it is important to understand the causes behind this implementation gap. Implementation Gaps While policies do exist, there have been multiple

gaps in the

translation of these policies into implementation that reduce the

impact. A progress study by HUPA in September 2013, showed that only 47%

of the dwelling units sanctioned under JNNURM had been completed. In

Punjab, 87% of the units sanctioned were either not started (48%) or not

completed (39%). The discrepancy between disbursement of Central

Assistance (ACA) and completion of dwelling units on the other is

particularly striking in some states and highlights implementation

difficulties. In Sikkim, 94% of ACA had been released, but only 17.7%

sanctioned dwelling units had been built. In Rajasthan, 73.3% ACA had

been disbursed, but only 19.3% of units had been completed. A year

later, only about 59% of the dwelling units sanctioned across the

country had been completed but 87.6% of committed funds were released.

Additionally only 43% units were actually occupied. Thus the scheme was unable to meet its target of providing shelter both due to units not being constructed as well as lack of occupation in the completed units. Low retention and acceptance of social housing projects is not just limited to JNNURM. Similar experiences have been seen in many other state and centrally sponsored housing schemes. A study to gain insights and a deeper understanding of the situation on the ground reflected some causes of these lack lustre statistics. They are illustrated below. Land ConstraintsThe responsibility for provision of land - a prime resource for housing lies with the government. Consultations with key stakeholders across various states in India revealed that a major bottleneck for affordable housing projects is adequate availability of land. Most medium to large cities do not have enough land near the city centre, thus slums and new housing projects (especially affordable) are relocated on the outskirts of the city, often beyond the municipal boundaries. This relocation adversely affects the displaced populace by removing them from their livelihood, often distancing them from basic amenities like markets, hospitals and schools. Travel routes are also not well developed especially in the smaller towns to ease the transition. This relocation is often quoted as the single most important reason for attrition and desertion of these allotted houses. Financial MismanagementThe HUPA JNNURM progress study found instances of fund diversion from housing projects towards other initiatives such as toilet construction (Jammu & Kashmir), DPR preparation (Jharkhand), agency charges (Haryana) etc. This has obvious adverse effects on progress. Another area of concern is the cost escalation due to inflation between the project planning and construction stages. The centres share is fixed. The urban local body or implementation agency often cannot bear this expense and they end up passing it on to the consumer. Further delayed release of funds as is often the case in government projects, exacerbates the situation. Projects often get stalled due to this reason. This was observed in self-financing schemes such as the Rajiv Swah Gruh Scheme in Andhra Pradesh where the implementation agency was unable to bear the costs and the scheme shut down. Quality of ConstructionConstruction of housing especially in the numbers required to meet the demand is very resource intensive. Resource efficiency in materials and technologies can go a long way in reducing this pressure on resources and the environment as well in reducing the cost of construction. However, they are often not mainstreamed in construction and the government schedule of rates that govern material use. Additionally, limited technical capacities of implementation agencies on these alternative materials and technologies retards the use of these options. While this is true for all housing and construction, the affordable housing sector faces a serious acceptance issue from users due to the common perception of these alternates. The Kerala experience shows that use of these technologies in institutional and high income construction creates a demonstration effect increasing acceptance within the LIG (Low Income Group) and EWS (Economically Weaker Section) sectors. Another concern among home owners is the small size of houses allocated. EWS houses are in the range of 21-27 sqm carpet area. This barely accommodates a bedroom, a common room and a tiny kitchen. The lack of privacy and overcrowding of 2 to 3 generations of the family in the same house is a major problem. Moreover, a HUPA study of a project in Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh found that while approved carpet area of each dwelling unit was to be 25.39 sqm, in actual construction the carpet area was 14.74 sqm and built up area was 20.96 sqm. Identification and Selection of BeneficiariesBeneficiary selection and allotment is one of the most politically coloured processes in these schemes. Politicians use housing schemes as a means to confer favours upon voters, thus political tussles often result in unnecessary delays in allotment. The CAG report by the HUPA highlighted this. A Development Alternatives (DA) study in Kerala and Madhya Pradesh in 2014 had similar observations. This political interference also colours repayment rates and schedules among the allocated units. Consultations with stakeholders in Andhra Pradesh estimated the non-repayment rate to be as high as 90% in certain pockets. Also surveys conducted for identification often have unclear eligibility guidelines. This process does not take into account adult children marrying and starting their own families in the duration of the construction and definitely does not account for future population growth. The DA study clearly brought this out as a major source of dissatisfaction among the beneficiaries. Ownership and TenureSuccessful community participation and engagement throughout the process of planning and construction enhances ownership as the Development Alternatives report highlighted from the Sangli experience. Moving from a predominantly horizontal ground based housing plan to an apartment as is the case with most schemes requires some time. Community based cooperative process can help ease the transition. Also valuing the asset provided helps build ownership. While a feeling of ownership can be created among beneficiaries through various approaches, tenure ship often creates security concerns. Studies conducted by Development Alternatives showed that most schemes transfer the house deed to the beneficiary after all instalments have been paid, with a caveat that prevents them from selling the asset for a period of 7-15 years. This in practicality is not enforced, thus people buy and sell (speculation) or sell and return back to slums (convenience). Also as the land belongs to the government, sometimes there are not clear documents that highlight the entitlement of the occupants, keeping alive the fear of eviction. Supporting Infrastructure and Living Conditions Not SuitableSupporting infrastructure plays an important role in determining retention. HUPA studies show that the reasons vary from proximity to garbage dumps to narrow approach roads that restrict movement of people and emergency services like ambulance, police van or a fire engine. Thus the social infrastructure and land development have to be undertaken simultaneously with the housing programmes to ensure that basic provisions and urban facilities are provided to the occupants. Thus some of the key aspects that policy makers need to consider while drafting and implementing housing and habitat policies are as follows: Appropriate beneficiary selection with timely allocation for occupation Use of resource efficient materials and technologies to maintain quality Appropriate size of houses that meet basic needs and privacy concerns Social infrastructure to be developed simultaneously with housing Appropriate financial tools and mechanisms in place between all stakeholders Exploring alternative innovative models like rental models qKriti Nagrath References http://pmindia.gov.in/ Sustainable Social Housing Initiative Stakeholder assessment Report , DA 2014 Indias Urban Awakening, Mckinsey Global Institute, 2010

|