|

Sustainable Lifestyles in

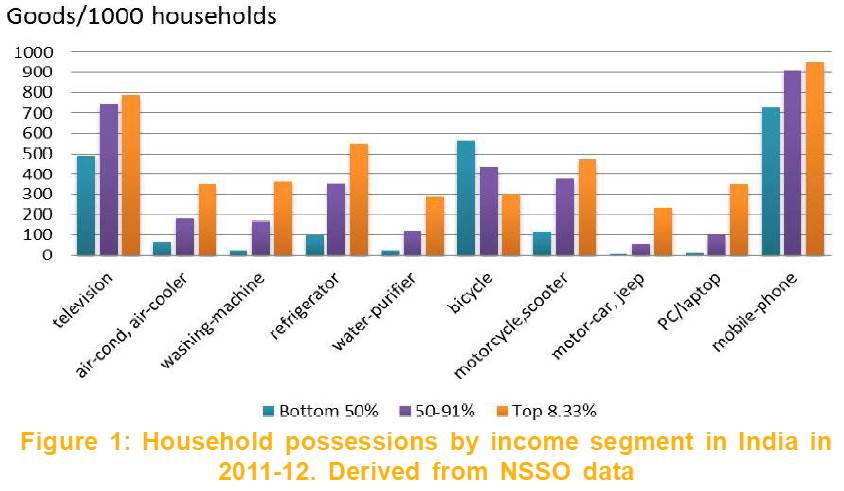

India I ndia as a country is undergoing dynamical change, most evident in the shifting configuration over the past two decades in the built environment, new forms of social relationships with stark gender differences across different strata, altered workplaces and technologies and rising inequality. The environmental impacts associated with these developments are daunting, both in terms of resource extraction and downstream waste generation. But in many ways, it is the social dimension of these changes that is most remarkable and significant for seeking alternative pathways towards sustainability.The context of these changes can be traced to the shifts in government policy that took place in 1991 in relation to trade and the liberalisation of markets. Indian society over the last two decades has quite explosively come into the midst of global markets, not only exposing it to sophisticated marketing strategies but also revealing new ways of life that have been common in Europe and North America for a while. Three features of Indian consumption are starting to become clear in relation to the context outlined above. Firstly, roughly every other Indian does not fully participate in the growing consumer economy of India. Apart from basic goods such as food, fuel and more occasionally, clothing, their association with commodities is quite meagre. The only exceptions to this seem to be mobile phones, televisions and bicycles, which are significant purchases for this group (see Figure 1) as they provide important services, namely, communication, entertain-ment and transport. Except for a few households in this category that possess ‘white goods’ such as refrigerators, air conditioners and washing machines, the majority live in sparse homes having few appliances if any. Mostly, they are entrepreneurs, small farmers, construction workers and employees in tiny firms. Even if they had the means to be nutritionally well off (although most are not), they are significantly deprived of a decent life because they lack capabilities in terms of access to resources, skills and education, safe working conditions, clean water, sanitation and so on. Secondly, the richer half of Indian society, in terms of household income or consumption, shows remarkable diversity and can be divided into two broad segments. The top 8% segment are part of what the World Bank terms the global middle class and they are indeed the most important segment to consider for understanding consumption patterns and lifestyles in India. This group has an income exceeding 10 dollars a day and includes households that are comfortably off, at least judging by their consumption patterns for food, clothing, fuel, education and health and their possession of ‘luxury’ capital goods. The remaining segment constituting a third of the Indian population includes medium-sized farm owners, factory workers, small business owners and franchisees, who either just make do or are on a trajectory taking them towards the richest 8 per cent. Because of the failure of the state to provide access to essential goods and services, such as education, health care, clean water, public transport and so on, there is a tendency especially within this group to seek private solutions for these which in turn leads to economically inefficient, socially harmful and environmentally disastrous outcomes. Private schools and colleges foster elite differentiation and create hierarchies of cultural capital, particularly around access to English. The increasing privatisation of health care with little or no regulation on medical costs creates incentives for the health care industry to inflate prices. Private cars, motorcycles, drinking water bottles, etc. reduce the pressure on governments to think seriously about public transport and associated land-use planning or fixing urban water supply and sanitation systems, because those better off do not complain loudly or bitterly about these things. Thirdly, global and domestic marketing strategies have been directed primarily towards the top 100 million, but are also intended to create commodities that could generate psychological associations with brands for everyone, including those at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’. Overall, the share of income spent on durable goods has risen from 2.7 to 6.1% in rural India and from 3.3 to 6.3% in urban India between 1993/94 and 2011/12 even though real incomes have not risen at the same rates, especially for the bottom half 1.

The richest 100 million in India are also characterised by what statisticians describe as having a fat-tailed distribution, with a small group of people owning enormous amounts of wealth. This is already underscored by the fact that India has over a hundred billionaires and is the fastest growing super luxury market in the world (for the most expensive cars, watches, accessories and so on). For the remaining tens of millions in the middle (those roughly between the 92nd to 98th percentile), there is increasing evidence from passenger transport, housing, space cooling and personal appliances that the absolute growth of luxury commodities in each sector is rising at faster rates than the rest of the economy. The choice of low or high footprint options is often not primarily driven by cost or even function, but by their symbolic value. For instance, the choice of purchasing fuel-guzzling SUVs in dense Indian cities is less likely driven by either cost or function, yet their sales have been galloping in recent years. How are we to make sense of these trends? The despairing news is that current consumption patterns are structurally constrained to be unsustainable. Trends in bicycle consumption provide us some important clues about why this is so. As Figure 1 suggests, the poor are reliant on bicycles for transport and have at least one in every household. Among the richest 100 million or so, bicycles are likely to be used as toys for children, for sport or at best as a ‘choice’ vehicle in contrast to being an ‘essential’ one for their poorer compatriots. Cycles on the road are increasingly at risk of being hit by heavier and faster vehicles, which starkly increases the vulnerability of the poor. And yet, cycles are perhaps the most sustainable technology available today for passenger transport. They are human-powered and therefore provide daily exercise. They have zero emissions and they are ideal for short trips under 10 kilometres, which is the majority of urban trips. The rich are more inclined towards SUVs, as we saw above, which are almost by definition the epitome of unsustainable transport. Even those seeking to make sound transport choices are often caught in a social trap where they are compelled to buy motorised vehicles because the built environment and lack of safe alternatives pushes them towards this option. But the popular sentiment is also to devalue bicycles, with the hype about motorised vehicles making them a ‘step up’ and the former a ‘step backward’ to pre-modern India. If our everyday practices and the symbolic value of the goods we consume tend to accentuate the positive qualities of the least sustainable options, then it is essential that we find innovative ways to reverse this situation. Policymakers can no longer afford to assume that technology or pricing strategies alone will be sufficient to effect a shift towards sustainability. The good news is that social movements that focus on alternative lifestyles are starting to emerge in India and elsewhere and are represented by a small but growing number of innovative groups such as Vikalp Sangam (www.vikalpsangam.org) and thealternative.in. They comprise measures to bolster the crucial third leg of sustainability, namely, its social dimension. Such groups have the potential to alter the aspirations of the poor and reorganise the ordering of symbolic value of goods and services by weighting them on the basis of environmental soundness, allocative and economic efficiency and social solidarity. q Sudhir Chella Rajan Endnote 1 NSS Report No. 555: Level and Pattern of Consumer Expenditure, 2011-12, MoSPI, Government of India. |