|

Extended Producer

Responsibility:

A strategy to achieve circular economy in plastic packaging

Countless

applications of plastic along with its matchless characteristics have

resulted in the exponential growth in its consumption across the globe.

Its durability, one of its hailed benefits, is at the same time being

reviled as the biggest threat the polymer is posing to the environment.

BBC recently reported the discovery of a plastic sandwich wrapper from

Scotlandís Cairngorms National Park dating back by almost three decades

with no signs of degradation, which clearly demonstrates its durable

nature and threat.

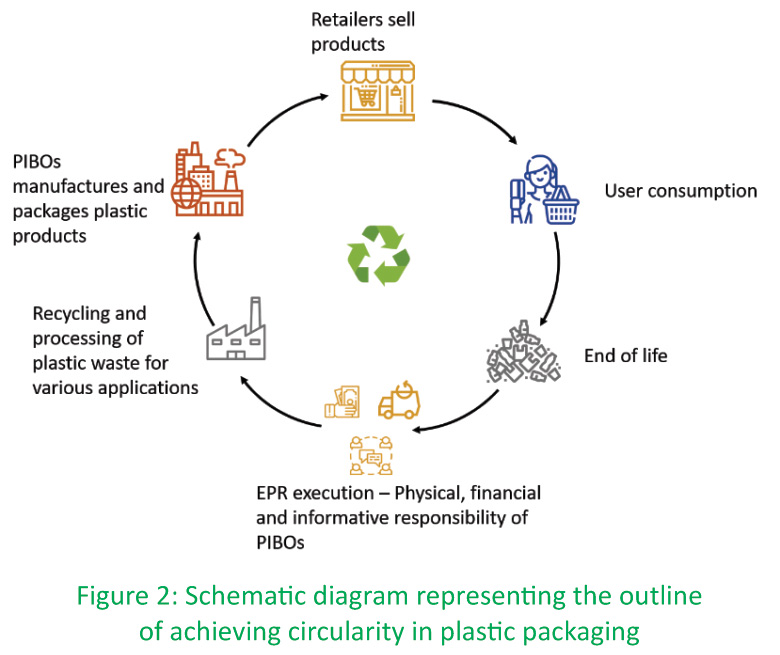

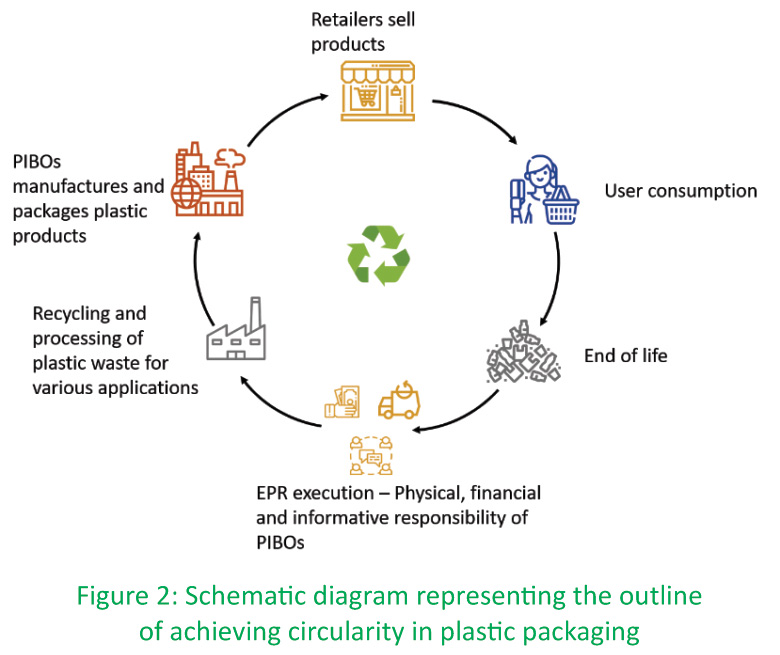

Based

on the 'polluter pays' principle, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

for the plastic sector was first introduced in India under Plastic Waste

Management (PWM) Rules, 2016. The rules imposed the onus of collection,

transportation, scientific disposal and management of post-consumer

plastic on its producers, importers, and brand owners (PIBOs). Though

the rules mandated installation of the waste collect-back system and

respective plan submissions by PIBOs to the state pollution control

boards (SPCBs), the lack of clarity of the mechanism, registration

norms, unpreparedness of PIBOs and poor municipal capacities resulted in

poor implementation of these regulations. Based

on the 'polluter pays' principle, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

for the plastic sector was first introduced in India under Plastic Waste

Management (PWM) Rules, 2016. The rules imposed the onus of collection,

transportation, scientific disposal and management of post-consumer

plastic on its producers, importers, and brand owners (PIBOs). Though

the rules mandated installation of the waste collect-back system and

respective plan submissions by PIBOs to the state pollution control

boards (SPCBs), the lack of clarity of the mechanism, registration

norms, unpreparedness of PIBOs and poor municipal capacities resulted in

poor implementation of these regulations.

It was in FY 2018 that the country started taking meaningful steps

aligned with EPR, following an amendment of the PWM rules providing

clarity on the registration norms. Recently, in FY 2020, the Ministry of

Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has introduced the draft

Uniform Framework for EPR, spelling out the responsibilities of the

centre, urban local bodies (ULBs), and PIBOs as well as other

specifications. Three models proposed in the framework for waste

collect-back systems include a polluter fee, Producer Responsibility

Organisation (PRO) and the plastic credit model.

Under the fee-based model, PIBOs are mandated to contribute to an EPR

corpus fund at the central level based on the normative cost borne by

ULBs to manage the waste generated. Under the PRO model, PIBOs rely on a

certified PRO who manages the recycling on its behalf for a negotiated

sum. Under the plastic credit model, PIBOs need not recycle their own

waste but recover/recycle an equivalent amount of waste to meet the

obligation. Under all models, PIBOs are mandated to furnish appropriate

evidence for the waste processed from accredited processors. The

framework has held the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) as the

body responsible for forming a national level PRO Association and

monitor and report the entire EPR mechanism.

The

countries that have successfully implemented the EPR have limited their

scope to specific types of plastic waste and have an established

segregation system. However, India's draft framework has not clearly

defined its scope nor does it have a solid segregation system. The

devolution of the EPR corpus fund from the centre to the local level can

improve its accessibility and reduce approval and permission timeline

enabling faster implementation. The framework currently based on the

'polluter pays' principle should take into consideration the strategies

to minimise the production by introducing regulations for design

improvements such as design for environment, design for collection, and

design for recycling/reuse to delay the end of life and provide other

incentives and impose punitive measures at the upstream sector. The

countries that have successfully implemented the EPR have limited their

scope to specific types of plastic waste and have an established

segregation system. However, India's draft framework has not clearly

defined its scope nor does it have a solid segregation system. The

devolution of the EPR corpus fund from the centre to the local level can

improve its accessibility and reduce approval and permission timeline

enabling faster implementation. The framework currently based on the

'polluter pays' principle should take into consideration the strategies

to minimise the production by introducing regulations for design

improvements such as design for environment, design for collection, and

design for recycling/reuse to delay the end of life and provide other

incentives and impose punitive measures at the upstream sector.

The framework should also consider listing feasible alternative

materials having evaluated its sourcing sufficiency and environmental

footprint in comparison to plastic. Additionally, systematising steps to

link back waste to its producers and ensuring proper enforcement and

monitoring, EPR will prove to be one of the powerful tools to curb the

plastic waste crisis in India. ■

References

Sherine Thandu Parakkal

stparakkal@devalt.org

Back to Contents

|

Based

on the 'polluter pays' principle, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

for the plastic sector was first introduced in India under Plastic Waste

Management (PWM) Rules, 2016. The rules imposed the onus of collection,

transportation, scientific disposal and management of post-consumer

plastic on its producers, importers, and brand owners (PIBOs). Though

the rules mandated installation of the waste collect-back system and

respective plan submissions by PIBOs to the state pollution control

boards (SPCBs), the lack of clarity of the mechanism, registration

norms, unpreparedness of PIBOs and poor municipal capacities resulted in

poor implementation of these regulations.

Based

on the 'polluter pays' principle, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

for the plastic sector was first introduced in India under Plastic Waste

Management (PWM) Rules, 2016. The rules imposed the onus of collection,

transportation, scientific disposal and management of post-consumer

plastic on its producers, importers, and brand owners (PIBOs). Though

the rules mandated installation of the waste collect-back system and

respective plan submissions by PIBOs to the state pollution control

boards (SPCBs), the lack of clarity of the mechanism, registration

norms, unpreparedness of PIBOs and poor municipal capacities resulted in

poor implementation of these regulations.  The

countries that have successfully implemented the EPR have limited their

scope to specific types of plastic waste and have an established

segregation system. However, India's draft framework has not clearly

defined its scope nor does it have a solid segregation system. The

devolution of the EPR corpus fund from the centre to the local level can

improve its accessibility and reduce approval and permission timeline

enabling faster implementation. The framework currently based on the

'polluter pays' principle should take into consideration the strategies

to minimise the production by introducing regulations for design

improvements such as design for environment, design for collection, and

design for recycling/reuse to delay the end of life and provide other

incentives and impose punitive measures at the upstream sector.

The

countries that have successfully implemented the EPR have limited their

scope to specific types of plastic waste and have an established

segregation system. However, India's draft framework has not clearly

defined its scope nor does it have a solid segregation system. The

devolution of the EPR corpus fund from the centre to the local level can

improve its accessibility and reduce approval and permission timeline

enabling faster implementation. The framework currently based on the

'polluter pays' principle should take into consideration the strategies

to minimise the production by introducing regulations for design

improvements such as design for environment, design for collection, and

design for recycling/reuse to delay the end of life and provide other

incentives and impose punitive measures at the upstream sector.