|

Policy Recommendations

for Up-Scaling Decentralised Renewable Energy in India A large percentage of rural India still lacks access to reliable forms of electricity. This is primarily due to a system of centralised energy planning which often ends up not catering to the ‘last mile connectivity’. A viable alternative is to consider decentralised renewable energy planning, wherein energy is generated at or near the end consumer.

While there have been government schemes to address rural electrification, these have not had the intended impact due to some fundamental problems. These problems include issues such as the Centre’s insistence on expanding the grid to remote locations, investors seeing micro and mini-grids as an unviable long term option, lack of access to credit. In instances where credit is being given, the capital based subsidies are either not easily accessible or are unable to ensure operation and long term sustainability of the plants. Guidelines to ensure grid competitive tariffs are in existence but mechanisms to ensure their adherence are not, therefore costs of generation are not covered 1.Following recommendations have been made in the three main stages that are crucial for up scaling decentralised renewable energy (DRE) plants: installation, operation and long-term sustainability. A. Installation 1. Improve Ministry Coordination It is essential that the Ministry of Power (MOP) and

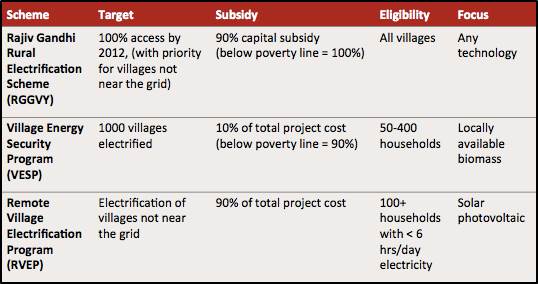

the Ministry State officials have an incentive to claim funds under both ministries resulting in an inefficient allocation of funds 2. The electrification responsibilities have been split between the MoP and the MNRE. This division is inefficient since grid-tied renewables suffer 30% transmission losses and solar for example is lost in a wasteful delivery network.One aspect that both ministries agree on is qualifying only the central grid to provide rural electrification. The MNRE’s Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vikas Yojana (RGGVY) aims to provide 100% rural electrification only by extension of the existing central grid and does not consider mini and/or micro-grids 3 and the MOP does not regard off-grid renewable energy systems to provide electrification; only the central grid qualifies for this4.Off-grid plants are contributing tremendously to provide electricity to tail end users and such government criteria undermine the overall goal of rural electrification. 2. Minimise Bureaucracy for Subsidy Provisioning Minimising bureaucracy can be achieved by standardising the necessary documents across the state or even the country. Making them available for download in an online portal makes these documents more easily accessible to developers. Furthermore, the creation of a ‘One-Stop-Shop’ for obtaining construction and operating permits can further simplify the process. It has been found that the time between applying for a MNRE capital subsidy and getting approval is upwards of half a year, a waiting time that can harm some developers. B. Operations 3. Focus on Results-Based Financing for Operation of Plants Variations in subsidy administration regimes pose a further challenge. The national target of 100% grid connectivity allows state electricity boards to provide operational subsidies to electricity producers that reduce the retail price of electricity to Rs 3/kWh. While the RGGVY scheme provides a capital subsidy to mini-grid developers, no operational subsidy is available. As a result, mini-grids are struggling to compete. 4. Tariff Middle Ground between Costs of Generation and Costs to Consumers The MNRE states that consumer tariffs for DRE electrification projects should be similar to those electrified through the grid and the Distributed Decentralised Generation (DDG) guidelines state that tariffs should be similar to existing tariffs in neighbouring areas. To address the economic viability gap between the current costs of generation from DRE plants and the costs to end consumers, there is need for a regulatory mechanism to spread out costs over all grid-connected consumers. Owing to the large numbers of grid-connected consumers, the incremental cost to individual grid-connected consumers will be negligible. Another option presented by the Forum of Regulators (FoR) called the Off-grid Distributed Generation based Distribution Franchise model (OGDGBF) is a sustainable business model which allocates budgetary funds 5.5. Close the Implementation Gap India has some good national policies in place that have the potential to provide a good framework on how to achieve rural electrification. But their implementation has either been handed over to state bodies or when the policies are actually extended to state level, on ground action does not seem to occur. An example is of the Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) framework which provides ambitious targets to states, but its enforcement becomes lax at the state level. |

|

Telecom Policy 2012 A good example of policy assisting in private sector risk is of the Telecom Policy 2012 which mandated cellphone tower operators to invest in the switch from diesel to hybrid renewable energy. To help in the switch, operators can now receive easy bank financing. |

|

C. Long-Term Sustainability 6. Transparency Over Central Grid Expansion and Grid Integration Central grid expansion is arguably the biggest uncertainty for developers and investors in decentralised renewable energy supply in India right now. In order to manage expectations and provide investment security, it is essential for national policy to provide a clear roadmap that lays out the schedule of the planned grid expansion. Furthermore, policy should provide clear guidelines for technical interconnection standards and tariff setting. Currently, not only does the goal of central grid expansion conflict with on ground realities, but lack of framework in place for grid integration belies any long term vision for this goal. 7. Viability Gap Funding from the Government As is the case with tariff setting, there is currently a gap between costs of generating power from decentralised renewable sources and selling to the consumer. This gap is primarily because of the high initial capital expenditure of setting up a DRE plant, shorter duration of power purchase agreements signed between investors and operators and the interest rates on bank loans. Investor confidence will build when there is assurance that the DRE plant will not be irrelevant 5 years down the line. Lastly, even a decrease from an interest rate of 12-13% to 8-9% will drastically impact generating costs. A combination of the above recommendations can potentially bring down the costs of generating by Rs. 10/KW which then brings down the costs to consumers, making DRE plant generated power closer to being competitive with grid power. 8. Expand the Renewable Energy Portfolio beyond Solar The government’s preference is to increase solar in the renewable energy portfolio, as is evidenced by schemes, large scale solar capacity addition and the recent decision to not enforce anti-dumping duties on imported solar technologies. However, the potential for biomass, micro-hydro and wind is not being realised and the costs to install off-grid plants using these forms of renewables are still high. The costs of solar are cheaper because technologies are imported, not because of strong domestic manufacturing. In addition to heavily promoting solar, the government needs to have a long term vision to strengthen wind technology manufacturing, biomass supply chain and expand the renewable energy portfolio. Conclusion Rural India has a significant unmet demand for reliable electricity service. Currently, most of the off-grid plants are set up and operated by private entities that have recognised the demand for electricity from rural households and enterprises. It just so happens that these private ventures are also in line with the governmental goal of providing rural electrification because access to reliable and affordable electricity helps support the growth and development of rural communities. It is thus beneficial for everyone to align these goals and provide for mechanisms that make the installation and operations of DRE plants easier and to have instruments that promote long term sustainability and scaling up of these plants. q Rowena Mathew Endnotes 1 Mathew, R. (2014). "Policy Imperatives for DRE based Rural Electrification in India" Development Alternatives Newsletter Vol. 24 No. 4. New Delhi. URL: http://www.devalt.org/newsletter/apr14/of_3.htm. 2 Kharul, RV. (2013). "Effective Policy and Regulation of Energy Access in India". MNRE Akshay Urja Vol 6 Issue 4: 36-40. New Delhi. URL: http://mnre.gov.in/file-manager/akshay-urja/january-february-2013/EN/36-40.pdf. 3 Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana. (2013). Annual Report. URL: http://rggvy.gov.in/rggvy/ rggvyportal /index.html. 4 United Nations Foundation. (2014). 5 Gambhir, A., Toro, V., and Ganapathy M. (2012). Decentralised Renewable Energy (DRE) Micro-grids in India. Prayas Report, Pune.

|

of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) improve the coordination of their

schemes and strategies in order to most optimally allocate resources.

of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) improve the coordination of their

schemes and strategies in order to most optimally allocate resources.