|

Gender

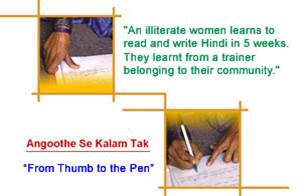

Perspectives and TARA Akshar+

T he Asia-Pacific region is home to three quarters of the world’s illiterate population. Illiteracy in the region is both a cause and consequence of poverty, deprivation and under-development. It is commonly accepted that the gains of development cannot reach the general population until basic education and liter acy

are provided to all. acy

are provided to all.

The literacy rate in India has improved considerably over the last decade. As per the data published by the 2011 census, India has managed to achieve an effective literacy rate of 74.04 per cent as compared to 2001 when the country’s literacy rate stood at 64.8 per cent. In seven states the female literacy rates are still below 60 per cent, with Bihar at 52.9, Rajasthan at 52.7 and Jharkhand at 56.2 per cent. This clearly proves that though numbers speak, they are unable to give us the right picture if we miss the pertinent qualitative aspects which reflect and depict the existing social dynamics. If one goes a little deeper, our social dynamics and biases against half of the population become apparent with male literacy rate being 82.14 per cent and female literacy rate 65.46 per cent, the gap between the two being 16.68 percentage points. The census data does not give a complete picture when one wants to view women’s status in a holistic manner in terms of their involvement, representation, their voices and struggles reflected on indicators like sex ratio, enrolment and drop out rates etc. Literacy is increasingly accepted as an ‘invisible glue’ for achieving many broader developmental goals which are vital to women’s empowerment. If women are educated they influence the behavior of the next generation for the better. But in rural India only 20-25 per cent women are literate. Compared to the urban female literacy rate in India, the rural rate is only one third of the former. Of the millions of school age children not in school, the majority are girls. Literacy is not merely about basic skills of reading and writing; it is about providing individuals with the capability to understand their lives and social environment as well as equipping them with problem solving skills. Literacy, therefore, is a foundation of human resource development. The education of women is particularly valuable as a strategic investment in human resources because the social returns of this investment are high. The government as well as the non-governmental sector plays an important role through the various policies and programmes in enhancing women literacy rates. This issue needs serious concern and has to be seen from the people’s angle. We have to go beyond discussing why female literacy is needed or reconfirming the correlation between literacy and empowerment etc. One needs to understand what works and what doesn’t work in the Indian rural scenario, what needs attention, what feeds the dynamics at grassroots level, what aspects need special focus and timely decisions. Without that ‘systems approach’ the Herculean task of getting more and more women literate is not going to be achieved. For example, even though there are schools in villages and efforts are made to make mid-day meals effective, the girls’ drop out rates are continually increasing. Similarly, discussions are held and programmes are implemented but girls are seen getting married before adolescence and women’s participation in the panchayati raj is still negligible. The ground realities need to be tackled and for that it is pertinent to understand what factors determine the participation of women in these programmes. Who are the important stakeholders, what are the motivating and demotivating factors, what efforts are needed to bring a change, what it actually means at different levels starting from planning to implementation, and how these aspects are dealt with in our policy formulations. Development Alternatives (DA) has made efforts in this direction after analysing some of the above mentioned aspects based on its long standing experience of working at the grassroots level. The TARA Akshar+ programme was thereby designed wherein learning is brought to the women’s doorstep at mutually agreed short duration time slots, as both girls and women have a lot of household and field work. Similarly, village women are more comfortable if they sit in an informal set up at a villager’s home rather than in a formal institution which may be well equipped but is remote and far from other habitations. So classes are held in an individual’s house in or around the central area of the village. Many such aspects were well integrated into the programme design to make it a well thought out literacy programme for women in rural India. It is an innovative computer

based functional literacy programme that trains rural women to read and

write in Hindi and also to carry out basic mathematical calculations.

This programme was developed in 2004 by TARAhaat Information and

Marketing Services Ltd. - the ICT arm of the non-profit organisation, DA

Group. The software application uses a unique visual memory technique

that links every letter of the Hindi alphabet to an object that the

female students use in their daily lives. This linkage helps rural women

to learn the alphabets quickly and remember them. A well-structured programme design and its thorough implementation have resulted in a very high degree of efficiency. Covering the Hindi speaking belt of the country, TARA Akshar+ has succeeded in educating approximately 70,000 rural women with a very negligible drop out rate. With the ongoing implementation of this wonderful programme things seem to be changing but on a rather slow pace, which calls for attention towards sustainability and scalability. For women like Radha Bai, TARA Akshar+ creates numerous opportunities as it has given her the capacity to command respect both at home and within the community. There have been instances where women objected on being prevented to appear for the TARA Akshar+ exams, and attended classes even when facing a difficult situation (death of a family member). These things need to be seen and documented together with well framed and validated outcomes of female literacy. Higher rates of school going children, better hygiene, improved nutrition practices and better care of the family health, better agricultural productivity and higher incomes and also reduced fertility and infant mortality, increased educational attainment, participation in decision making concerning a daughter’s marriage and her education, women’s own role in village level affairs in terms of participation and leadership , higher productivity thanks to enhanced skills and confidence to engage in productive work outside the home etc. There is an enormous scope for research to identify indicators of empowerment, to do causal loop analysis and enquire into biases due to habits of the mind. Thus, one cannot expect simple, quick and direct results. Much research needs to go into this angle in addition to dealing with the set of challenges which occur during implementation of this work on the ground under diverse conditions. q

Alka

Srivastava

|