|

Behaviour Change Communication

- The Need for Action Research

Introduction

How does behaviour change occur? How is behaviour change sustained?

These questions probably have as many answers as there are diverse

populations and cultures. The underlying principles may not be formally

recognized as theories, but they focus behaviour change efforts on the

elements believed to be essential for individuals to enact and sustain

behaviour change.

Three of the most commonly cited theories literature are outlined in

this article: The Belief Model, the Stages of Change, and the Theory of

Reasoned Action. This is then juxtaposed against the theory of community

participation. The role of dialogue processes in behaviour change

communication is then highlighted concluding with a need for further

action research in this arena.

Belief Model (BM)

The Belief Model (BM) is a psychological model that attempts to explain

and predict behaviours by focusing on the attitudes and beliefs of

individuals. The BM was developed in the 1950s as part of an effort by

social psychologists in the United States. Since then, the BM has been

adapted to explore a variety of long- and short-term health behaviours.

The key variables of the BM are as follows (Rosenstock, Strecher and

Becker, 1994):

• Perceived Threat: Consists of two parts: perceived susceptibility and

perceived severity of a condition.

• Perceived Susceptibility: One’s subjective perception of the risk of

being in a debilitating condition,

• Perceived Severity: Feelings concerning the seriousness of being in a

debilitating condition (e.g., poverty)

• Perceived Benefits: The believed effectiveness of strategies designed

to reduce the threats.

• Perceived Barriers: The potential negative consequences that may

result from taking particular actions, including physical,

psychological, and financial demands.

• Cues to Action: Events, either bodily (e.g., physical symptoms of a

health condition) or environmental (e.g., media publicity) that motivate

people to take action. Cues to action are an aspect of the BM that has

not been systematically studied.

• Other Variables: Diverse demographic, socio-psychological, and

structural variables that affect an individual’s perceptions and thus

indirectly influence related behaviour.

• Self-Efficacy: The belief in being able to successfully execute the

behaviour required to produce the desired outcomes. (This concept was

introduced by social psychologist Albert Bandura in 1977.)

Limitations

Most BM-based research to date has incorporated only selected components

of the BM, thereby not testing the usefulness of the model as a whole;

As a psychological model it does not take into consideration other

factors, such as environmental or economic factors, that may influence

health behaviours; and the model does not incorporate the influence of

social norms and peer influences on people’s decisions regarding their

health behaviours

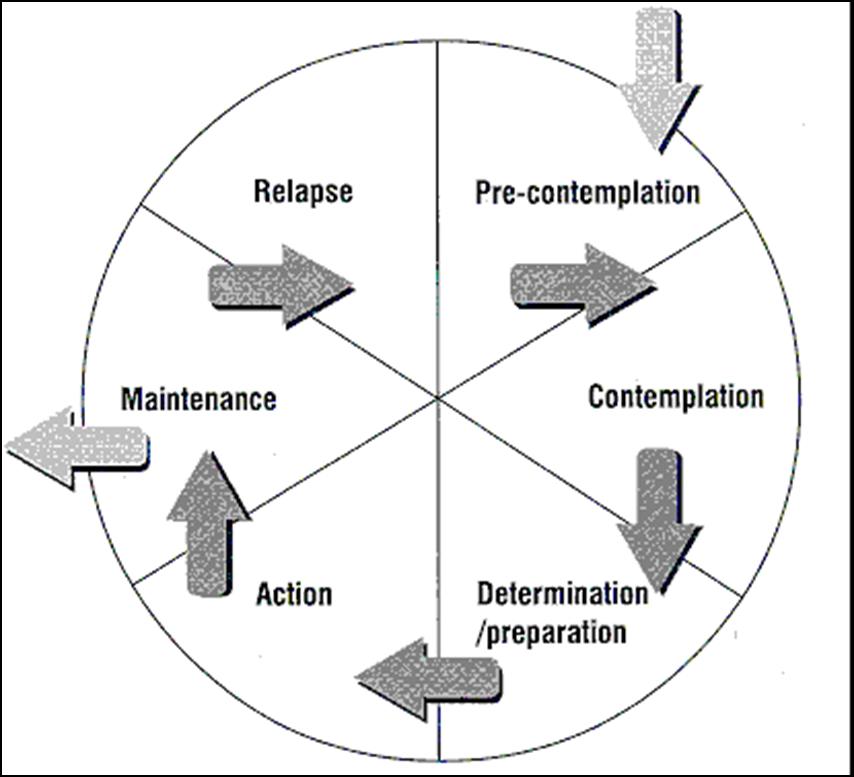

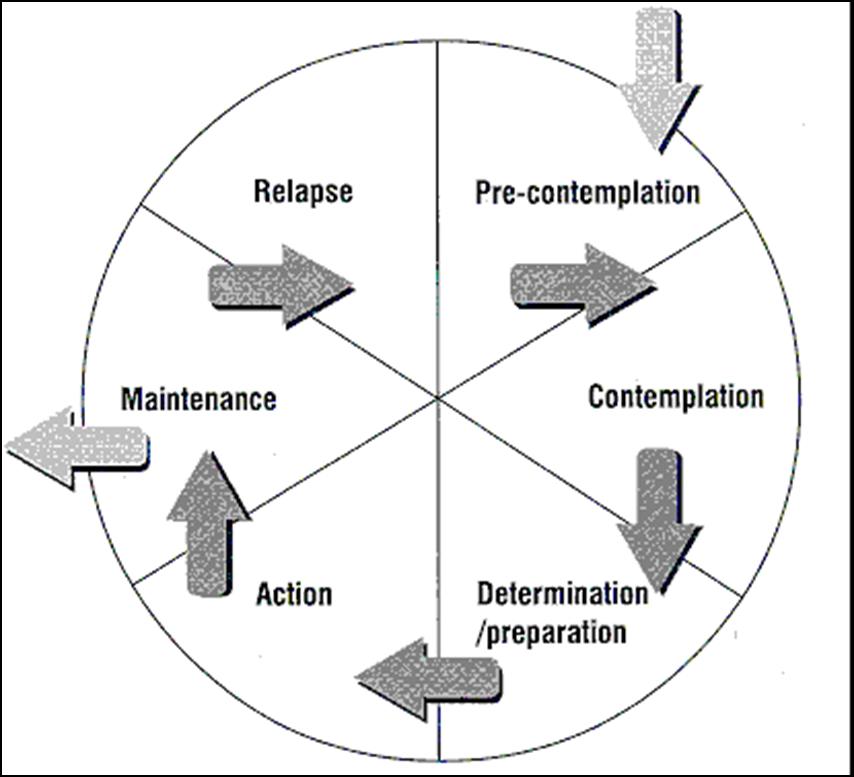

Stages of Change

Psychologists developed the Stages of Change Theory in 1982 to compare

smokers in therapy and self-changers along a behaviour change continuum.

The rationale behind “staging” people, as such, was to tailor therapy to

a person’s needs at his/her particular point in the change process. As a

result, the four original components of the Stages of Change Theory

(pre-contemplation, contemplation, action, and maintenance) were

identified and presented as a linear process of change. Since then, a

fifth stage (relapse) has been incorporated into the theory that helps

predict and motivate individual movement across stages. In addition, the

stages are no longer considered to be linear; rather, they are

components of a cyclical process that varies for each individual. The

stages, as described by Prochaska, DiClemente and Norcross (1992), are

listed below.

• Pre-contemplation: Individual has the problem (whether he/she

recognizes it or not) and has no intention of changing.

• Contemplation: Individual recognizes the problem and is seriously

thinking about changing.

• Preparation for Action: Individual recognizes that there is a problem

and intends to change the behaviour within a specific time period (e.g.

the next month). Some behaviour change efforts may be reported. However,

the defined behaviour change criterion has not been reached.

• Action: Individual has enacted consistent behaviour change for less

than a relatively long period of time (e.g. six months).

• Maintenance: Individual maintains new behaviour for prolonged periods

of time (e.g. more than six months).

• Relapse: Individual repeats the original behavioural pattern after a

period of ‘Maintenance’

Limitations:

As a psychological theory, the stages of change focuses on the

individual without assessing the role those structural and environmental

issues may have on a person’s ability to enact behaviour change. In

addition, since the stages of change presents a descriptive rather than

a causative explanation of behaviour, the relationship between stages is

not always clear. Finally, each of the stages may not be suitable for

characterizing every population.

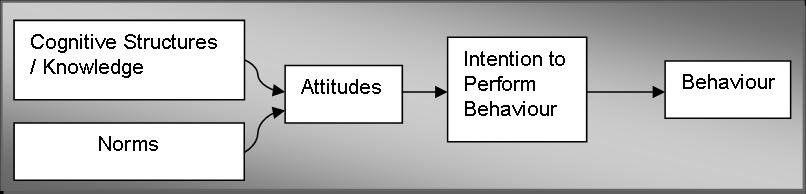

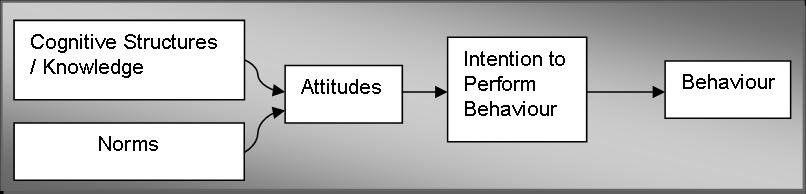

Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA)

Research using the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) has explained and

predicted a variety of human behaviours since 1967. Based on the premise

that humans are rational and that the behaviours being explored are

under volitional control, the theory provides a construct that links

individual beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviour (Fishbein,

Middlestadt and Hitchcock, 1994). The theory variables and their

definitions, as described by Fishbein et al. (1994), is as follows - A

specific behaviour is defined by a combination of four components:

action, target, context, and time.

• Intention: The intent to perform behaviour is the best predictor that

a desired behaviour will actually occur. Both attitude and norms,

described below, influence one’s intention to perform behaviours.

• Attitude: A person’s positive or negative feelings toward performing

the defined behaviour.

• Behavioural Beliefs: Behavioural beliefs are a combination of a

person’s beliefs regarding the outcomes of a defined behaviour and the

person’s evaluation of potential outcomes. These beliefs will differ

from population to population.

• Norms: A person’s perception of other people’s opinions regarding the

defined behaviour.

• Normative Beliefs: Normative beliefs are a combination of a person’s

beliefs regarding other people’s views of behaviour and the person’s

willingness to conform to those views. As with behavioural beliefs,

normative beliefs regarding other people’s opinions and the evaluation

of those opinions will vary from population to population.

The TRA provides a framework for linking each of the above variables

together. Essentially, the behavioural and normative beliefs – referred

to as cognitive structures - influence individual attitudes and

subjective norms, respectively. In turn, attitudes and norms shape a

person’s intention to perform behaviour. Finally, a person’s intention

remains the best indicator that the desired behaviour will occur.

Overall, the TRA model supports a linear process in which changes in an

individual’s behavioural and normative beliefs will ultimately affect

the individual’s actual behaviour. The attitude and norm variables, and

their underlying cognitive structures, often exert different degrees of

influence over a person’s intention.

To date, behaviours explored using the TRA include smoking, drinking,

signing up for treatment programmes, using contraceptives, dieting,

wearing seatbelts or safety helmets, exercising regularly, voting, and

breastfeeding (Fishbein et al., 1994).

Limitations:

Some limitations of the TRA include the inability of the theory, due to

its individualistic approach, to consider the role of environmental and

structural issues and the linearity of the theory components.

Individuals may first change their behaviour and then their

beliefs/attitudes about it. For example, studies on the impact of

seatbelt laws in the United States revealed that people often changed

their negative attitudes about the use of seatbelts as they grew

accustomed to the new behaviour.

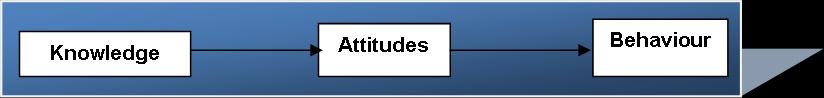

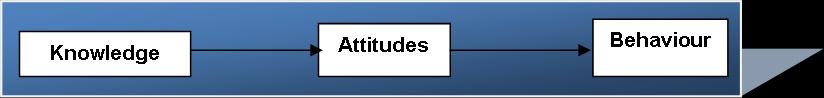

Overall

Overall, the merging of components from various theories is common, as

researchers and programmers seek to gain a better understanding of how

behaviour change occurs.

The current integrated theoretical discourse follows the linear process

that outlines an increase in information or knowledge leads to change in

attitudes which in turn lead to behaviour change.

The study of behaviour change communication has been limited to the

field of health and sanitation till so far. However, civil society

organizations such as DA has been attempting to change the behaviour of

people along various other parameters including climate change

adaptation and mitigation, agriculture, livelihoods, enterprise

development, etc.

In this context it becomes imperative to contextualize the theories

involved in behaviour change to both the local context and the specific

behavioural targets.

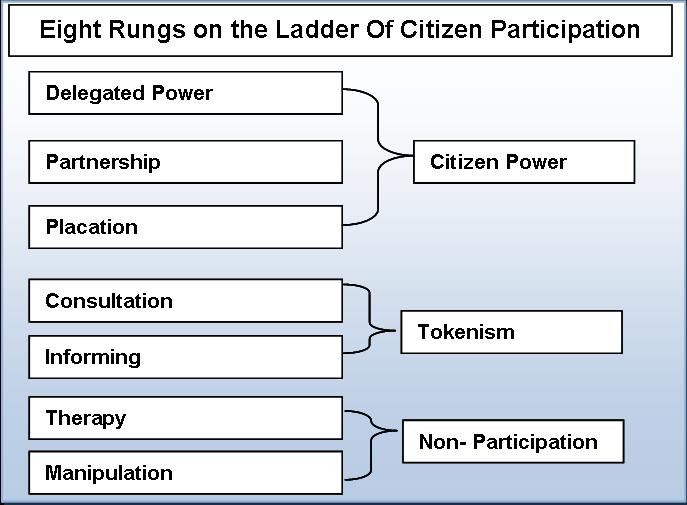

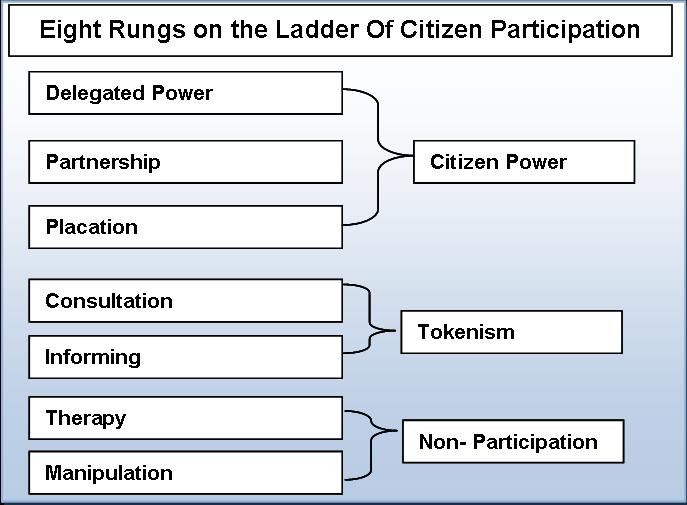

Community Participation

The discussion about the sustainability of any behaviour change has been

positively co-related to the degree of community participation.

Community participation involves a power-sharing relationship between

communities and decision-makers.

There are varying degrees of power available to the community. Arnstein

(1971) describes a ladder of degrees of citizen participation, providing

a framewo rk

to aid consideration of how to involve the public. rk

to aid consideration of how to involve the public.

It is no hidden fact that the agenda of behaviour change is often driven

by external factors. The most specific being a funding organisation. The

civil society organisation involved in grassroots level work, driven by

donor agenda, attempts to enforce specific behavioural targets on the

community with minimal participation from the community members.

It is in this context that the concept of dialogue becomes prominent.

However, given that much of the theory of Behaviour Change Communication

is derived from therapeutic work with individual clients, it poses a

logical conflict on at least two levels.

1. Applicability of the theories to large scale grassroots

2. Degree of participation involved

Suggestions

In the light of these dilemmas, Behaviour Change Communication while

used as a strategy for grassroots level developmental work incorporates

two major activities. The first of these activities is identifying key

people in the community who are willing and able to induce the desired

changes among people in the community and building their capacities to

influence other people’s behaviour. This can be achieved by doing

training programmes in various counselling, governance and participatory

tools.

The second and more prolonged activity is supportive supervision so that

the trained volunteers/animators are able to see fruition of their work

through the continuous consultation with experts.

Both these activities address to some extent, how large scale behaviour

change can be influenced as well as raises the participation from mere

behaviour manipulation to change in behaviour based on1 mutual

consultation.

Such strategies have been adopted and proven in the sector of health in

India within Bundelkhand.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be stated that the theories of behaviour change

and behaviour change communication are very individualistic and

prescriptive. Further action research is required to systematize

Behaviour Change Communication specifically to technological innovations

and addressing climate change issues by influencing adaptation and

mitigation practices at the grassroots.

Sudeep Jacob Joseph

sjjoseph@devalt.org

References

• Bandura, A. (1989). In V. M. Mayes, G. W. Albee and S.F. Schneider

(Eds.), Behaviour Change: Psychological Approaches (pp. 128-141).

London: Sage Publications.

• Rosenstock, I.M., Strecher, V. J., & Becker, M. H. (1994). The belief

model and HIV risk behaviour change. In R.J. DiClemente & J. L. Peterson

(Eds.), Preventing AIDS: Thories and Methods of Behavioural

Interventions (pp.5-24). New York: Plenum Press.

• Brown, L. K., DiClemente, R.J., and Reynolds, L. A. (1991). HIV

prevention for adolescents: Utility of the Health Belief Model. AIDS

Education and Prevention, 3 (1), 50-59

• Fishbein, M., Middlestadt, S.E., and Hitchcock, P. J. (1994). Changing

Health Behaviours. In R.J. DiClemente and J. L. Peterson (Eds.),

Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioural interventions (pp.

61-78). New York: Plenum Press.

• http://www.healthknowledge.org

.uk/public-health-textbook/medical-sociology-policy-economics/4c-equality-equity-policy/consumerism-community-participation

q

Back to Contents

|

rk

to aid consideration of how to involve the public.

rk

to aid consideration of how to involve the public.