hroughout the 21st century

and thereafter, global climate change will have

The Climate Change Centre in Development Alternatives is extensively involved in helping the rural communities to adapt to the changing climate. As part of this, a short research study was conducted by the Centre to understand the traditional adaptation practices by the vulnerable communities in a drought prone area. The study makes an effort to : n Understand the role of traditional coping measures initiated by the communities; n Identify the response measures and policy initiatives already taken up by Government and other stakeholders (Funding agencies, NGOs); n Analyse gaps in the existing policies, and n Suggest refinement of existing Government policies and programmes.

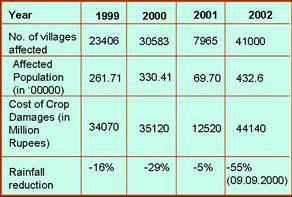

The State of Rajasthan experiences an arid, semi-arid climate resulting in severe drought, the magnitude of which varies from year to year. Drought has been a continuous phenomenon in Rajasthan since the beginning of the 20th century. The severity of drought has been more intense in the last couple of decades with 1987-88 and 2002-2003 being most severe. The intensity and frequency of drought in Rajasthan is expected to increase in the coming years due to climate change. Based on meteorological evidences, it was found that the Tonk district was worst affected by the drought of 2002. Tonk was chosen as the representative survey area since it is located in the heart of Rajasthan. It truly depicted the climatic variations that took place in the state of Rajasthan. The present study was conducted in two severely affected villages in the district of Tonk, ie Dotana and Safipura, with a population of 1400 and 300 respectively. The average size of the family is six to seven people per household. The main occupation of the people is agriculture and animal husbandry. Impacts of Drought : Scarcity of water There was hardly any water in the ponds, wells and hand pumps. Nearly 30 percent hand pumps have now dried up and the same percentage goes for dysfunctional systems. Reduction in incomes Scarcity of water resulted in massive crop failure in the drought years. The daily wages of labourers were reduced from Rs 60-70 per day to Rs 30-40 per day. Due to immense crop damage, there was scarcity of fodder and higher prices of available fodder resulted in the abandoning of the livestock. This again, reduced incomes as livestock is one of the main sources of income generation. Adverse impacts on literacy Villagers send their children to Government schools as primary education is free. But, some money (in terms of books, minimum annual fees, transportation costs) is always required to be spent. With successive occurrence of drought, villagers find it difficult to meet even these minimum expenses, so they discontinue their children’s education. Adverse impacts on health Medical facilities are absent in most of the villages. The hospital is located at the block headquarters (10-15 km away). They save money to meet unexpected health related expenses. They have to hire a vehicle to go to the hospital – all this means expenses that they can scarce afford. Traditional Adaptation Practices by the Communities: Less water-intensive crops

The land holding size differs from person to person but the average size of land holding is 0.5 hectares. Due to reduced water availability the farmers have stopped growing crops which require greater amount of water such as cotton. The farmers have successfully adapted to crops requiring less water and started growing cumin seeds, grains and some oilseed crops like mustard. The crops like grains, cumin seeds and mustard were introduced by the local NGO to the villagers. Storage of food-grains and fodder The farmers store grains for utilisation in future, but the quantity is only sufficient for meeting their requirement for one year (due to less production). Fodder for cattle is difficult to get during drought, so they store fodder as much as possible. Small mud structures are used for storing food grains and fodder. The traditional mud structures can preserve the contents for a year or two. But unfortunately the farmers do not have that amount of food-grains or fodder to store. The farmers, over the years, through their knowledge and experience could predict the monsoon and spend on inputs (seeds, tillage) accordingly. The sale of stored food grains also depends on their prediction, which normally works well. The older generations are still very efficient in predicting the monsoon. Increasing water availability The main sources of water are ground water and rainwater stored in ponds. Some of the practices adapted by the villagers to get water in water scarce situations include activities like digging of new ponds, deepening of existing ponds and wells, bunding of agricultural fields and construction of anicuts. Bunding of fields Large scale leveling and bunding of fields is being practiced by the villagers. They construct med bandhi (contour bunding) in the agricultural field to check water in a piece of land. This reduces wastage of water by allowing the excess water from the field to flow to adjacent fields which are at a lower elevation. Bunding and anicuts structures thus allow optimal utilisation of water by the crop. Digging and deepening of ponds Programmes such as digging new ponds and deepening of existing ponds have been taken up by the villagers on a voluntary basis. However, some of these programmes are also supported by the State Government. Interventions for Additional Adaptation: Introduction of medicinal plants

The experts from the NGO introduced Sona Mukhi, a medicinal plant, as a revenue generating plant in arid and semi arid region. It requires less water and minimum care for its growth. The plant is also not grazed by domestic or wild animals, therefore it has little need for protection. Sona Mukhi is widely used in Ayurveda, Unani, Sidha, Allopathy and other traditional medicines mainly because of the laxative property of its aerial parts. Ten kilogram of seeds is required for covering one hectare of land. Cost of one kilogram of seed is just Rs. 200. Seeds, once sown in one hectare of land, generate Rs 50,000 as revenues each year, for at least five years. The leaves are used in ayurvedic medicines. The seeds are used for the next sowing and as the crop blooms fully at least three times in a year, the seed can also be sold in the market. Minimising fertiliser use through vermi-composting After the successful field demonstration of the vermi-compost technology, the people found it to be a low investment and less cumbersome process and adopted it immediately. This provides a two way benefit over use of synthetic inorganic fertilisers. Firstly, the soil fertility and its productivity are not degraded and this is a viable option for sustainable agriculture. Secondly, they require less water and inorganic fertilisers, which saves money. After some capacity building in the technology, the villagers are now able to prepare vermi-compost on their own. Water management The traditional practices adopted by the villagers were not sufficient to meet their demand for water requirement. They are now conserving water by preparing anicuts which helps to store water. This also helps in recharging the ground water in nearby land, aquifers and the wells. These communities were not aware of conserving water through anicuts but the awareness generated by local NGOs helped them to practice this conservation structure. Fodder crops and vegetables The communities are now growing fodder to a great extent which is benefiting their cattle as well as enabling them to earn some extra money. Vegetables also provide monetary and nutritional benefits. Formation of Self Help Groups (SHGs) About 100 women of these villages have formed a self help group, Mahila Mandal. Each woman member of the household contributes Rs. 10 per month to a fund managed by 20 women. They lend this money for different purposes like serious health problems, to buy seeds from the market, to dig wells and so on, but the decision to lend money depends on the seriousness of the issue. Outcomes of Interventions: Improved water availability (through construction of anicuts) - n for human consumption : Unlike earlier years, water for drinking purposes is now available almost throughout the year n agriculture: The water conservation structures (anicuts) have helped the villagers get water for irrigating the agricultural fields during winter as well as during the next cropping season. Improved water management through - n cultivation of less water intensive medicinal plants and fodder crops n vermi composting to retain soil moisture Improved incomes through - n revenues from growing medicinal plants and selling its leaves and seeds which are in very high demand n better cattle rearing due to improved availability of fodder and cultivation of fodder crops n cultivation of vegetables Enhanced food and nutritional security through - n diversification of agriculture: Besides growing adequate staple food crops, due to better availability of water the community is now able to grow vegetables during the winter season, which gives them higher revenue, more balanced nutrition and a cushion against crop failure. Lessons Learned : Strong presence of local NGO helps The strong presence of the NGO has benefited them tremendously and they sincerely acknowledge it. The villagers realised the benefits of the presence of NGO and within a couple of years accepted them. Empowerment of villagers absolutely essential The ways to overcome water crisis should be communicated to the people. Training should be imparted to the villagers on any innovative technique being introduced by any stakeholder. Simpler agricultural risk mitigation schemes required In spite of repeated crop failure in Rajasthan, the state has not launched an effective Crop Insurance scheme to compensate the losses. The present Crop Insurance scheme has several weaknesses – its limited coverage, cumbersome procedure and time consuming settlement of claims. Establishment of market linkages Market linkages are needed for sale of crops by establishing well regulated ‘mandis’ at centres close to the villages, improving earnings from milk and other dairy products (through formation of co-operatives) selling medicinal plants etc. Improvement in Government services The improvement of rural infrastructure such as roads, communication, cold storages etc and reducing the gap between planning and implementation through effective monitoring and evaluation of Government programmes certainly helped. One of the most important learnings from the study is that more emphasis needs to be given to preparedness rather than relief. q

Udit Mathur & Dr. Anish Chatterjee umathur@devalt.org achatterjee@devalt.org

|

significant

impact on the human and other species on this planet. Global

temperatures are projected to increase by up to 5.8

significant

impact on the human and other species on this planet. Global

temperatures are projected to increase by up to 5.8