| The Ten Million Challenge Sachin Mardikar

for the Tenth Five Year Plan, more than ten million people in India will be seeking work every year. Thus, to ensure full employment within a decade, more than ten million new livelihoods will have to be generated each year. Given the magnitude of the problem, and the dearth of resources for livelihood promotion, the task of promoting livelihoods for the poor becomes all the more urgent. It calls for organisations to use their resources optimally to achieve maximum scales. Given the North-South and East-West divide in almost all aspects, it is clear that most of the work seekers will come from UP, Bihar, Jharkhand and MP. The PACS programme works in all the above states and therefore it is imperative that livelihood challenge be looked at with greater focus. This article looks at the issues related to Livelihood Promotion and the out of box thinking needed to generate the critical mass to bring about sustainable change in rural India. What is Livelihood? Any Livelihood1 intervention should aim to keep a person meaningfully occupied in a sustainable manner and with dignity. Any livelihood intervention should evolve around these three important tenets. When we talk about being meaningfully occupied in a sustainable manner, we are referring to creating conditions that encourage an individual to contribute his/her skills and capacities in a productive manner so that a person is able to fulfill his/her household needs. This means that any activity that generates economic returns for the person so engaged, can be called sa livelihood activity. The catch being that it should not be a one time thing but done repeatedly. The dignity aspect is crucial to what we would call as desirable livelihood promotion activity. Dignity refers to socially, ethically and legally acceptable activity. This obviously excludes a host of activities that do produce economic returns but as a responsible civil society, we need to ask ourselves whether this is what we intend to promote. Why to Promote Livelihoods/Employment? In the Indian context, about 64 per cent of those classified as main workers by the census, depend on agriculture whose share in GDP is regularly falling and today stands around 32 per cent. This means close to two thirds of the population is dependent on one third of the national income2. Hitherto, we believed that promoting industries in a large way would absorb the growing labour from the rural areas. This has unfortunately not happened. If we look at many of the industrialised states such as Maharashtra and Gujarat, the rural Average Monthly Per Capita Consumption Expenditure (AMPCCE) in 1999 was lower than the national average. Quite clearly, the modern smoke and chimney led model has failed to provide the alternative to job seekers. Where do these millions of youngsters go is the central question that should concern everyone. Can we, as partners in the civil society, look at this issue critically? At a broader level, the underlying belief in promoting livelihoods is the essential right of all human beings to equal opportunity. Poor people do not have life choices, nor do they have access to opportunities and that perpetuates the state of poverty. Ensuring that a poor household has a stable livelihood will substantially increase its income, and over a period of time, asset ownership, self-esteem and social participation. Yet, another reason for livelihood promotion is to promote economic growth. The ‘bottom of the pyramid’ comprises nearly four billion out of the six billion people living in the world, who do not have the purchasing power to buy even the bare necessities of life – food, clothing and shelter. But as they get steadier incomes through livelihood promotion, they become customers of many goods and services, which then promote growth. The third reason for promoting livelihoods is to ensure social and political stability. At this stage, it would be quite interesting to correlate the prevalence of hunger and poverty and the general state of law and order in a region. The Livelihood Challenge in rural areas Rural areas are different. A few years ago, during one of the assignments, I tried to map the informal businesses in the city of Nagpur. In about two days, our team came up with a list of 181 different types of informal enterprises that thrived on just two main roads of the city. This may not be the case in rural areas, where life is less interdependent. A good number of these informal enterprises were, in fact service providers to the main actors. In that, they supported a complex maze of livelihood support systems. Contrast this with a typical village, which has less interdependency. This severely restricts the opportunities for promoting varied livelihood enterprises. But, this does not deter people from building up a basket of livelihoods through which they survive. Some of the other challenges relate to: l Limitations of agriculture: A significant proportion of rural population is still believed to be dependent on agriculture, but the assumption that agriculture will continue to generate additional livelihoods in the future, has severe limitations. Often, the loud claims being made about how agriculture is the largest job provider appears to be misleading, when we compare it with the contribution to the national GDP. Over the years, prices of agriculture commodities have remained stagnant. The input costs, however, have gone up creating a situation where most people work at a quarter of minimum wages.Any modernisation or development of agriculture is likely to throw up more and more able bodied persons in the job market, thus intensifying the competition. In states such as UP and Bihar, the problem could be acute because of high population density. l Lack of marketable skills: As the economy progresses there is a perceptible difference in the societal requirements. Products and services that were in great demand till recently may have no takers. It is just not enough to be able to produce, but produce marketable goods. This is tricky because of the issues related to access, awareness and attitude which severely restrict the choices that a rural youngster may have. Probably, their urban cousins who migrated have picked up these skills.The rural India, over the last decade, has seen a virtual flood of micro credit movement through self help groups. Different practioners have been following different models, but the underlying objective in almost all the cases is similar - that of credit self sufficiency. Even the government has kept an ambitious target for credit to these SHGs. This takes us to another dimension that is - Is The Paradigm Shift I had the opportunity of traveling in the remote villages of Jharkhand and MP. What struck me was the near absence of energy in any of its common form that we know of in rural India. There was no electricity, diesel, petrol or kerosene. Talking to tribal farmers there, I gathered that most did not use bullocks for tilling the land and few, if at all, possessed any agriculture implement. But, my meeting with Raju Ooram, a tribal young man in Kuragi village of Ghagra Block, Jharkhand, provided an entirely new perspective (See the Box). This incident forced me to take a re-look at my own biases from an urban middle class perspective. Much of these biases originated from my flawed understanding of the societal learning curve. The telecommunications explosion has changed the complexion of rural India forever. One of the fastest growing markets in rural India is cosmetics. One of the first uses of assured electricity is entertainment.

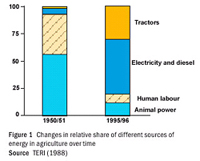

I believe there is a case for rethinking the way we have always conceptualised rural livelihoods. Conventional approaches and solutions have a tendency to produce results that could be predicted with great accuracy. And, this is why perhaps, we need to think beyond goats and sheep. Probably, the last most dramatic livelihood initiative that changed rural India was Operation Flood or Amul. I shall now talk about some of the emerging options that have the potential of livelihoods creation. l Water and Energy-centric Livelihoods: A case here could be for development of energy-based livelihood systems. In rural India, the capacity to generate wealth gets severely hampered because of the energy deficiency. Four out of six PACS States receive a normal rainfall (except MP and Maharahstra). The livelihood interventions, therefore, could be around harnessing the available water resources in a better way.The agriculture sector is the second largest energy-consuming sector in rural India. Three activities in this sector account for most of the energy used: land preparation, harvesting and irrigation (water lifting and transportation). Irrigation is the most important end-use of energy. Animate energy (human and draught power) caters to over one-third of the total energy consumed. An estimated 15 million electric and six million diesel pumps are currently in operation in the agriculture sector of the country. Diesel oil and electricity are the major sources of energy for irrigation. The share of oil and electricity in the final energy consumption of the agricultural sector has increased steadily over the years. The sector now accounts for one third of the overall demand for electric power, mostly for water lifting, which is provided by the state utilities.

A look at the agricultural inputs, in terms of energy and non-energy, can give new insights into the livelihood opportunities. For example, a pump is nothing but a device that can transport water into the fields of a farmer. Out of the multiple options that a farmer has, it is likely that he finds a diesel pump much superior to his existing water delivery technology (such as Rahat) and has a better energy-output ratio (input energy per unit of delivered output). In other words, what he is buying is an energy solution and any other device that can better these ratios will find precedence over the pump. With the exception of Marathwada in Maharashtra and parts of MP, the rest of the states under the PACS programme do receive good rainfall with slightly better soil conditions. And yet, this is also the region that has the highest incidence of poverty. What is required is an intervention that could make it possible to utilise this water judiciously. Affordable water delivery technologies, such as the treadle pump or drip system developed by IDE, have the potential of improving water productivity. l Skill Based Livelihoods: Another area worth looking at, is the development of livelihood clusters that are based on local skills and have strong regional market linkages. A UNIDO study3 in 1997, clearly bought out that industrial clusters have remained concentrated in Western and Northern parts of the country. Further, it highlighted that about 91 per cent of the clusters have developed naturally, while only about nine per cent are induced clusters due to policy initiatives by the government. And thirdly, a majority of the clusters (71 per cent) have developed due to their size and proximity to the markets, whereas only 24 per cent of them are resource based and just about five per cent are based on infrastructure.This is interesting because we always tend to blame the lack of infrastructure followed by lack of resources as major bottlenecks in growth. What emerges then, is the fact that proximity to markets is the key driver of livelihoods and one only has to visit places like the Mumbai-Pune-Nasik Triangle in Maharashtra or the Lucknow-Kanpur-Allahabad cluster in UP or Ranchi city, which is a major vegetable centre. In each of the cases, the strong pull of the markets has ensured sustainable livelihoods for the population that lives in surrounding areas. l Reducing Shocks and Vulnerability: Perhaps, one of the most significant contributions that we could make would be to reduce the shocks and vulnerability of the poor. Thanks to the new initiatives that are being taken by NGOs, private sector and the government, micro credit and micro insurance have emerged as new options for the rural poor. One is also looking beyond micro finance into livelihood finance.Constraints and Opportunities There are tremendous challenges involved in promoting livelihoods in most of the districts where PACS works. Large parts of Marathwada lie on hard rock and historically have never witnessed three consecutive years of good monsoons. Similarly, in North Bihar, floods have become an annual ritual. Hence, choices in the agriculture sector are very limited. Although no official level data is available, but one is perplexed looking at Gujarat state, which has witnessed a boom in generating livelihoods around the water pouch. Today, the water pouch economy is booming in the state, providing livelihoods to thousands. Can we promote, for example, clusters that are based on finance, labour, material and markets? This is interesting because some communities with whom we work such as Banjaras in Marathwada have been known to play an important role in agricultural development of Western Maharashtra, mainly the sugarcane farms. Similarly, Jharkhand witnesses large scale migration to plantations in the east and as far as Punjab. In the same vein, there could be regions that are net importers of goods and others that have surplus capital. In Maharashtra, the Banjara and other communities can negotiate a better wage deal with the farmers of the Western Maharashtra. This single intervention could trigger off significant changes in the income levels of millions. But, this requires a change in conventional thinking as understanding natural clusters is an interesting way of looking at livelihood promotion. We need to recognise the existing arrangements and only then intervene in a manner that builds upon the existing skills and capabilities. Unless we learn how to leverage what we have, instead of trying to do everything, I am afraid we cannot promote livelihoods in a large way. What we may at best succeed is in creating a few hundred more micro enterprises, which will be a mere drop in the ocean. qThe author is a Nagpur based consultant. He is part of the resource team

References 1 A Resource Book for Livelihood Promotion, New Economics Foundation, Datta Sankar, Mahajan Vijay, Thakur Gitali 2 Phansalkar, S.J (Saadhan) 3 UNIDO,1997 | ||||||