|

Women Health and Nutrition

Maithili

Sharan Gupt, national poet, wrote:

Abla jeevan hai tumhari,

Aanchal mein hai doodh

aur ankhon mein pani

The

persistence of hunger and abject poverty across the world is largely due

to the subjugation, marginalisation and disempowerment of women.

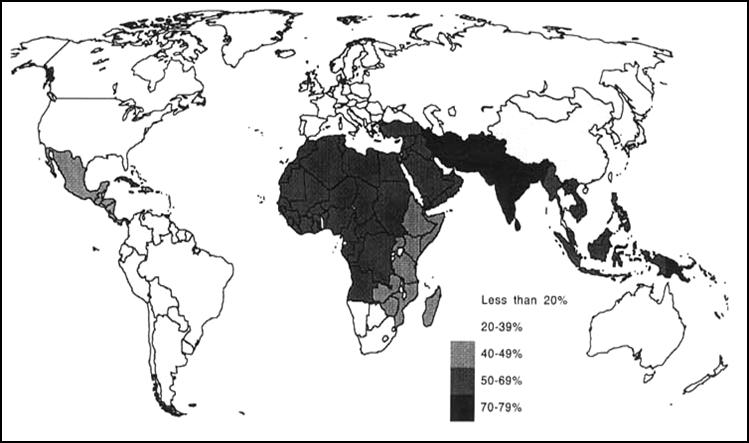

Malnutrition, defined as the state of being underweight, is a serious

public-health problem linked to a substantial increase in the risk of

mortality and morbidity. Women and young children associated with

malnutrition bear the brunt of the disease burden. In Africa and South

Asia, 27"51% of reproductive women are underweight1, and it is predicted

that about 130 million children (21% of all children)2 will be

underweight in 2005. Many of the 30 million low birth weight babies born

annually (23.8% of all births) face severe short-term and long-term

health consequences.

Malnutrition is both a cause and a consequence of poverty. It can create

and perpetuate poverty, which triggers a cycle hampering economic and

social development and contributes to unsustainable resource use and the

resultant environmental degradation.

The nutritional status of women and children is of particular

importance, because it is through women and their off-spring that the

pernicious effects of malnutrition are propagated to future generations.

A malnourished mother is likely to give birth to a low birth weight (LBW)

baby susceptible to diseases and premature death, which only further

undermines the economic development of the family and society, and

continues to propagate the vicious cycle of poverty and malnutrition.

The concept of improving women’s nutrition for their own sakes - rather

than just as mothers - needs to be fostered. There is no doubt that a

woman whose basic nutritional and health needs are met will be in a

better position to meet the needs of her family. Specific nutritional

deficiencies such as those of iron and iodine must be tackled (and they

can be, at low cost), with all women forming the target group. Better

targeting of supplementary feeding at those most at risk of

malnutrition, and job creation and literacy programmes will help to

address the more intractable problem of protein-energy malnutrition. The

nutritional status of women can also be considerably influenced by

attention during adolescence, with ‘spin-off’ benefits also available to

their future.

The critical role of female literacy in improving women’s overall health

and nutritional status needs to be well recognised. The coincidence of

girls’ adolescence and school drop out rate signals the need for

focusing on education systems on keeping the girls in schools. This may

be done through providing special incentives, public education and

offering alternative forms of education. It is important to provide

basic vocational skills, enhancing girls’ employability, and delaying

their marriage until they are physically prepared to bear children.

While these are longer-term goals, in the short term, efforts must be

increased to specifically improve women’s knowledge of health, nutrition

and hygiene. The communication of basic nutrition information - based on

a proper understanding of existing knowledge, attitudes and practices -

and involving health workers, primary school teachers, women extension

officers, and other frontline workers reinforced by appropriate use of

the mass media can help empower the women to successfully address the

burning issue of malnutrition. q

Dr. Virendra Kumar Vijay

Raghwesh Ranjan

rranjan@devalt.org

Back to Contents

|