|

CDM in the Forestry

Sector in India The Ninth Conference of the Parties (CoP9) of the Climate Change Convention held in Milan, Italy during December, 2003 has approved CDM in the forestry sector particularly in the sequestration of carbon through aforestation and reforestation activities. In fact, CoP9 will be known as the forestry CoP. The developing countries who are party to the Kyoto Protocol can now avail this benefit of carbon credits from their forestry activities. The present paper therefore deals with some of the aspects of forestry sector in India and its sequestration capacity. Further, as part of the implementation process of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Earth Summit, June, 1992), all signatories have to prepare an inventory of sources and sinks of greenhouse gases.We have initiated a research programme to assess the present and predicted sink capacity of our forests and CO2 emissions from development activities. This will help design appropriate response strategies. Initially, the programme focuses on evolving a methodology for a first-order assessment of the sink capacity of Indiaís forest. The total forest cover that includes dense forest, open forest and mangrove is estimated to be 63.73 million hectares, constituting 19.39 percent of the countryís geographic area. Out of this, 11.48 percent is dense forest, 7.76 percent is open forest and 0.15 percent is mangrove forest. There has been an increase of 2,896 sq. km. of forest cover between 1997 and 1999 assessments. Scrub land has also diminished during the period due to over-grazing and conversion for other uses including agriculture. Non-forest area has increased during the period mainly due to the population pressure on land or forests. Sequestration Capacity of Indian Forests A first-order assessment of the CO2 sequestration capacity of Indian forests till the year 2000 has been computed by taking the growth rate of Indian forests as reported in the State of Forest Report. The recorded annual production of stem wood in the country has varied from 26 million cum. to 32 million cum. The average annual production of stem wood in the country works out at 30 million cum. The unrecorded annual production in the form of fuel wood is estimated at 22 million cum. Thus, the average annual wood production is 52 million cum.The sequestration capacity has been computed in two ways: by volume of biomass and by total forest area. The total volume of wood production is converted into total biomass by assuming a mean wood density 0.52 ton/m3. The ratio of total biomass to usable stem biomass was assumed by the German Bundestag to be 1.6 for closed forest and 3 for open forest. In this present analysis, an average figure of 2.3 has been assumed. One cum. of stem wood is therefore equivalent to 2.3m3 of total biomass. One cum. of biomass (stem, roots, branches, etc.) absorbs 0.26 tonnes of carbon (tc). Since the annual production of biomass from the Indian forests is 52 million cum, the total annual CO2 sequestration capacity of our forests works out to be approximately 31 million tc (mtc). However, if we assume the carbon sequestration figure given by R.A. Sedjo (Forest to offset the Greenhouse Effect, Journal of Forestry, 1989, 87.7: 12-15.) for tropical forests as 6.24 tc/ha/yr and adopt the same for the total Indian forest cover of 64 mha (1991), the sequestration capacity of Indian forests is very encouraging. The total annual sequestration capacity of Indian forest works out to be 399 mtc (1479 million tonnes of CO2 emissions) which is practically 10 times more than the sequestration capacity computed by taking the total volume of biomass (31 mtc). The total CO2 emissions from the fossil fuels recorded in 1989-90 is 152.9 mtc. Considering that dense forest cover not only provides a carbon sink but also preserves biological diversity, urgent steps are required to speed up afforestation and reforestation activities in India, more so to take advantage of the recently approved CDM project activities in the forestry sector. Opportunity for Indian Forestry

The numerous beneficial impacts of forests,

particularly with regard to the impact to land management, are

universally known. Afforestation and reforestation moderate

the climate and precipitation regimes of a given area; prevent soil

erosion and increase the water retention capacity of the land;

increase soil fertility by ensuring the perennial addition of

organic matter to the soil; and thereby both reverse land

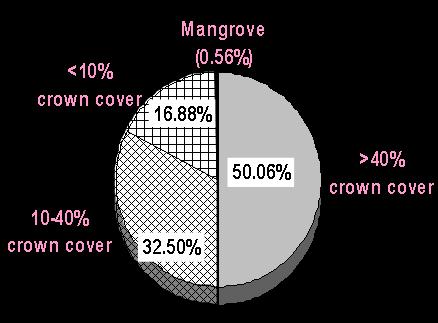

degradation and increase its commercial value. India has about 13 million hectares of fully degraded forests (see figure below; for the purpose of this article, forest areas with less than 10% crown cover have been considered fully degraded), and is in urgent need of both afforestation and conservation. Unfortunately, the government is unable to invest the amount of money currently needed to ensure afforestation and reforestation at the required scale. A part of this vast problem could be resolved through CDM forestry projects undertaken by India. Such projects will provide both the necessary funds and technology to achieve the goal of increasing CO2 sinks capacity of the Indian forests. Such afforestation and reforestation activities could then be continued under the countryís normal forestry programme. Efforts to promote CDM projects in the forestry sector would help fulfill its chief objective: the stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Additionally, these initiatives would fulfill basic conditions stipulated by the FCCC, namely that such stabilization be achieved within a time-frame of sufficient length, so that ecosystems would be enabled to adapt naturally to climate change; that food production not be threatened; and that economic development be enabled to proceed in a sustainable manner. Afforestation and reforestation activities pursued under CDM project activities represent an opportunity to abate GHG emissions in India, since forests possess considerable Co2 fixation potential as well as achieve sustainable development to help the forest community to improve their quality of life. The present annual rate of aforestation in India is about 2 million hectares (under various programmes such as social forestry, watershed development and wasteland development). CDM aforestation activities undertaken in degraded forest lands (excluding wastelands) could significantly increase this rate, while providing the funds and technological assistance. Interestingly enough, the capital cost of planting biomass in degraded forest areas is relatively low compared to the development of other renewable energy sources. If the areas to be afforested for CO2 sequestration are not exploited as energy sources, the required investment level will fall somewhere between US$100 to 600 per hectare, with an average of around US$250 per hectare (IPCC1990). But, even these relatively low levels of investment would probably exceed the current funding capacity of the Indian government. Current levels of fund disbursement have only sustained a net land use change (afforestation minus deforestation) of 92,500 hectares (1993 estimate). Here again, the purview of CDM allows for the circumvention of this problem, for these financial requirements would be met by monetizing carbon sequestered through CDM afforestation and reforestation projects. Therefore, it becomes quite

clear that CDM activities in the forestry sector offer considerable

opportunities to reclaim and afforest degraded forest lands, an

important land management objective. While important issues of

national sovereignty and ownership of afforested areas and

participation of local communities in CDM activities would have to

be negotiated prior to the commencement of the initiatives, the

potential benefits are obvious. Therefore, India should

capitalize on the present CDM initiative in the forestry sectors.

|

||