|

Safe Drinking Water -

Current Policy Scenario and Alternatives Context W ater quality is a major concern throughout the developing world. Drinking water sources are under increasing threat from contamination, with far-reaching consequences on the health of children and on the economic and social development of communities and nations. Although access to drinking water has improved from 1900 to 2010, water quality is still a major issue and mechanisms to ensure the same are not stringent. Diarrheal diseases lead to the death of about 1.8 million people worldwide1 and over 3 lakh children in India every year2. 21% of communicable diseases are related to unsafe water3 and 59% of the total health budget in India is spent on addressing the negative health impacts due to water pollution.Assuring that the water that reaches people is safe is a challenge for government and authorities in-charge for the same. However, till the time mechanisms for providing safe drinking water to everyone 24*7 are put in place, there is a need to promote interim solutions. There are many gaps in the current policy mechanisms to ensure access of safe drinking water to the last mile. Institutional

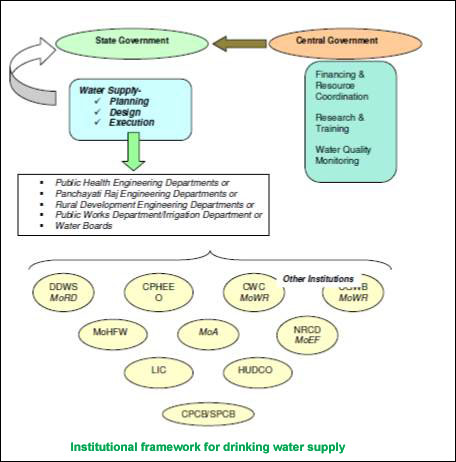

Framework In India, water is a State subject with the state being responsible for planning, designing, construction, operation, quality assurance and maintenance while the Centre provides technical and financial support. At the Centre, the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation (MoDWS) is responsible for water supply in rural areas. For urban areas, the responsibility is with the Ministry of Urban Development (MoUD). At the state level, local governance institutions viz. Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) and Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) are responsible for water supply. Besides these, more than a dozen agencies are responsible for water and play a crucial role in the supply chain. Hence, inter-sectoral coordination is critical and is a major bottleneck in the implementation of schemes and policies. Quality Standards Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) has specified drinking water quality standards in 1991 i.e. BIS 10500: 1991 which got revised in 2012 to BIS 10500:2012. The standards were designed to provide safe drinking water. The exhaustive standards prepared by BIS are merely recommendatory in nature and not mandated, implemented or monitored through a statutory framework. MoDWS and MoUD have provided guidelines to states to follow these standards, but no strict action is taken if these standards are not followed by the states. Moreover, there is disparity in permissible limits between various agencies. For e.g. in arsenic, the prescribed limit is 10 ppb (parts per billion) by the World Health Organisation (WHO) whereas that prescribed by BIS is 50 ppb. MoDWS has developed Uniform Drinking Water Quality Monitoring Protocol for rural India to ascertain meeting the prescribed standards for drinking. In this context, MoDWS has earmarked 3% of the National Rural Drinking Water Programme funds to the states for water quality monitoring and surveillance. The funds will be used for setting up/upgrading laboratories at various levels. In order to ensure access to quality water, funds have been spent on establishing laboratories, buying/upgrading water testing equipments and capacity building of Local Bodies/ASHA/ANM workers. Despite this, limited information is available in public domain on quality of water supplied through the sources. There is information on number of water samples collected and tested but limited disclosure on the quality of water supplied. Regulatory Mechanisms The market is swamped with household water treatment products. However, there remains ambiguity on standards and regulations related to quality and risk management. Quality, safety, health and environment concerns need to be scrutinised far more closely to safeguard the consumers. It is often seen that information on shelf life, service life, precautions, safety issues, replacement of filters, end of life indication, disposal etc. is not explicitly mentioned. The quality of output water is also not assessed continuously to estimate the efficiency of the filter. Lack of regulatory mechanisms for water treatment products leads to spurious products flooding the market. Efforts are underway to develop standards for products that specifically address water treatment challenges in India. The BIS has published standard IS 14724: 1999 for water purifiers that use UV technology and the BIS is also developing standards for RO and other disinfection technologies. Despite government efforts, pace of the industry is very fast. There is a huge gap between development of regulatory mechanisms and penetration of technology in the market. Consumer Behaviour and Responsibility Water contamination can occur at any point in the whole sequence of water supply. The government is responsible for providing safe drinking water at source. However, if proper or hygienic conditions are not maintained in water storage, there is high risk of secondary contamination. Hence, there is a need to influence behaviours of consumers regarding household water treatment methods, safe storage techniques and hygiene practices. The various ministries/departments working on water have funds for Information, Education and Communication (IEC). They realise the need for effective IEC to influence behaviours but lack the capacity to utilise the funds effectively. Majority of funds allocated for IEC lapse as the government focuses on water quality campaigns only in the monsoon season when the chances of waterborne disease outbreaks are high. Recommendations To ensure access to safe drinking water, Development Alternatives has been advocating point -of - use Household Water Treatment and Safe Storage (HWTS) methods as an interim measure till the time there is 24*7 safe drinking water. The following recommendations are made to address the policy lacuna and address access of safe water: 1. Inter-ministerial/agency coordination: To address the fragmented approach at the state and central level with the involvement of numerous agencies in the supply and management of water, better co-ordination amongst ministries and departments would ensure effective implementation. The option of a single nodal ministry with the overall supervision and administration pertaining to water resources may be looked into as is the case in Australia. 2. Set up a HWTS Mission as a high priority National Initiative (preferably under the MoUD/MoHUPA or Health Ministry) for a 10 year time period. Designate a Central Ministry as the Nodal Agency for promoting HWTS and community level water treatment systems to facilitate adoption of such measures till there is access to safe drinking water 24*7. 3. Norms for Water Safety: There is a need to develop acceptable limits of water quality standards and set them as mandatory for all the agencies supplying water to the consumers. For ensuring the regulation in place, there is a need to make suitable provision for integration of drinking water in the Food Law Bill. 4. Disclosure on Water Quality: The quality of water supplied by state ministries, ULBs through various sources should be disclosed. The disclosure of water quality will serve a dual purpose. Firstly, people will know the quality of water that they are receiving from a particular source and whether it is bacteriologically and/or chemically contaminated. Secondly, this will facilitate people in choosing the appropriate HWTS method or using another source of water. This will also increase accountability of the government and facilitate in improving the quality of water supplied. Tamil Nadu Water Supply and Drainage (TWAD) Board disclosure on the quality of water supplied through various sources is a good example to replicate. 5. Behaviour Change Campaigns: To influence behaviours, designing and rolling out behaviour change campaigns on water quality is an important mechanism. This will require convergence among the relevant ministries/departments working on water. The campaigns should create awareness on the correlation of water and health, Household Water Treatment and Safe Storage (HWTS) methods, hygiene and sanitation practices. The campaigns should be ongoing for some years, as short term activities will only lead to building awareness but will not bring a change in the behaviour. 6. Third Party Validation of Water Treatment Products: There is a need to formulate disclosure norms for water treatment products which should be validated by a third party before the product enters the market to safeguard consumer interests. There is also a need to reduce the gap between standards development and technology advancement. The focus of Central and State agencies is more on providing access to water. However, mechanisms to ensure access to safe drinking water are just as crucial. q References: Kavneet Kaur Endnotes 1 www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/diseases/burden/en/2 http://www.thehealthsite.com/news/over-3-lakh-children-in-india-die-annually-due-to-diarrhoe a-related-diseases/ 3 http://water.org/country/india/ |