| Technology Democracy for poverty reduction Zeenat Niazi zniazi@devalt.org

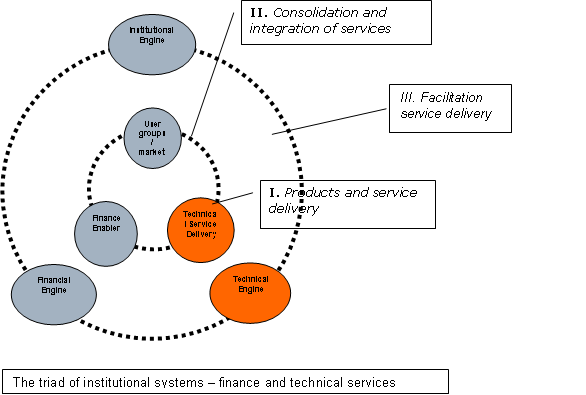

The current era of globalization is strongly driven by progress in technologies. Technological change drives wider changes in the economic, social, cultural and political life. In the multi-economic, multi-cultural scenario of developing nations, benefits of advances in technology have primarily reached those within developed economies, especially in the urban contexts. Large numbers of people in developing nations who are poor, especially those in rural regions, have been excluded from the benefits of technology development. They have little or no control over the environmental, social, economic and political processes that influence technology development and its application. Majority of technological innovations (that are recognized and promoted for larger application) occur in large industrial sectors. The technologies that do provide results are not necessarily affordable or accessible by the poor. Globalization has created an aggressive market based economy that stretches into almost every neighbourhood of the world. The sweeping changes it has brought about have outstripped the capacity of ordinary people’s existing technology. Either indigenous technology in its present state is not productive enough or the goods produced are not of the acceptable quality to compete in the new global market. Technologies that can provide for the basic amenities of people, while at the same time enhance their incomes and enable them a place in this global market (or help create their special market systems), are extremely rare. While government poverty alleviation programmes do focus on welfare – ‘food for work’ type of initiatives, the question on how technology development and its application can answer the rising levels of poverty is not being asked. While acknowledging that poverty alleviation or even its reduction cannot be achieved through a technological route alone, the application of technologies and delivery of technical services have a big role to play in livelihood creation, thus influencing poverty reduction. It, therefore, becomes important to address the “delivery” technology based livelihood services and enhance the access of the poor to these services that would enable them to rise out of the abject poverty they are in. Examples of myriad “appropriate technologies” exist for the want of “viable delivery mechanisms” that have never progressed beyond the pilot application stage. These were technologies for fulfilling the basic needs such as improved cooking stoves, fuel, water filtration and such like. Examples also exist of “manufacturing technologies” that use local rural resources to produce goods that sell in global markets and have made a difference in the lives of the rural manufacturer. The successes are based not on technological innovations but on marketing geniuses and efforts. The need for Technology Democracy Each system must, however, be able to deliver similar levels of quality and dignity of life and livelihood. Varied examples have shown that institutional arrangements, technical services and finance are critical components of any delivery system. These components need to work in a concerted and synergistic manner so that livelihood creation takes place in a sustainable manner. This triad comprising institutions (including markets), technology and finance has been designed well to deliver integrated services to urban upper and middle class economies. Take the case of housing. Today, it is easy for an urban citizen to select options of technology, financial products and methods of construction in order to access a house. Various options for land development, finance, and construction in the combinations of developers, contractors, home loans and self build options exist and are accessible through fiscal and other supports to urban populace. But the poor - both urban and rural - neither have this luxury of options, nor the ability to mix and match service delivery routes to suit their requirements and pockets. This holds good for other services ranging from providing health and education to goods and transport. If we analyze the social and geographic contexts of the economies of the poor, we find that in most cases these three critical components of institutions (whether market or social), technology and financial products exist in isolation from each other. So, while building technologies that are appropriate for the rural situations do exist, financial services that may make these accessible to them do not. Similarly, mechanisms of organizing customers so that they can form viable markets are only now emerging in the form of aggregated self-help groups. Even these are only seen as extended markets for the FMCG giants as users of their products and not as customers that need specialized products and customized services. This is even more complex when we consider basic needs services. If services such as water, sanitation, energy and habitat are to reach all, even the poorest, the system design that incorporates the three critical components needs to work in their specific contexts. This essentially requires the poor to be included in the discussion to design the system and set it in place. The principles of inclusion and dialogue are at the core of any democracy. Clearly, the “right system for the poor” can only be designed through an approach of Technology Democracy. The few examples of technology working for the poor indicate that the “delivery mechanism” for livelihood technologies and services is context specific, decentralized and linked with but not dependent upon other systems and market mechanisms. Again, this model does not preclude the existence and application of different scales and types of options / system designs. In fact, it is strengthened by variety and diversity that enable choices to be made in different contexts. Technology Democracy is thus supported and strengthened by Technology Pluralism. This resonates with the concepts that Mahatma Gandhi had advocated and Fritz Schumacher had developed upon half a century ago; that of decentralized, right scaled technologies that are manageable and controllable by users in a given context. Add to that decentralized and right scaled “services” – technical, financial and market based – that can reach basic needs or goods to people’s door steps, all the while creating livelihoods in large numbers. The journey so far Participants at the conference agreed that existing indigenous technology knowledge and practices across the region

do have an important, valid and necessary role to play in poverty reduction. Currently, this is neither formally recognized nor supported in the domain of science and technology agendas. As a direct outcome of the conference, participants agreed to set up a regional forum with multi-stakeholder participation from south Asian Countries with an agenda to promote “technology democracy” in the region. The conference was followed by a meeting in Colombo, Sri Lanka, to define a strategy and action plan for the forum. At this meeting, participants reiterated that South Asia needs:

While the work on this forum, which was being led by ITDG Sri Lanka, has had a setback due to the recent Tsunami, it is no less relevant today than it was two years back when this concept was mooted. Delivery of technical services as an instrument of technology democracy: The big advantage of looking at the design of delivery systems for providing services in rural areas is that service delivery itself has the potential of creating livelihoods. Development Alternatives energy program is finding out how the delivery of smokeless chulhas and fuel briquettes is as much an opportunity for earning as is their production as well as sale. Similarly, delivery of housing services by artisan self-help groups[1] in Orissa is providing livelihoods, while at the same time supporting incomes of brick makers, toilet pan manufacturers and other material providers in the villages. As formal rural finance systems open up, it becomes all the more necessary that these technologies “for the poor” are redefined as technical services and that service delivery itself becomes a means of livelihood creation. Moreover, the concept of service delivery necessitates a contact with and a response to the needs of the customer. Services, and therefore delivery mechanisms will need to be designed to suit the pockets, paying capacities and technology absorption capabilities of the poor. The learning from our experience of delivery of habitat services in Rural Bundelkhand shows that although the demand for cost-effective building systems has opened up with the availability of habitat finance (through customized products available from the State Bank of India), the critical factor is the delivery agent who can translate the building technology options into services at the doorsteps of the rural customer. The sustainability of service delivery depends as much on the technology options being demanded and offered as on the financial viability of this delivery agent and on the ability and knowledge of this agent to help his/ her customers make the right choice. . Customer response also makes it necessary to enlarge the basket of options – not just of technologies but also of financial services. This also brings in possibilities and potential of mixing and matching technology options by the customers, thus making technology pluralism a reality. The Janatakshina platform – or People’s Technology Forum, as initiated at the Colombo meet last year has a long way to go and its success it appears would be to enable supports for the “delivery of customized technical and financial products and services to the poor, by the poor”. This article has developed from the discussions of the October 2003 Conference on Technology For Poverty Reduction organized by ITDG, Sri Lanka and subsequent discussions in Colombo on issues of technology democracy. Credit is also due to the Rural Innovation Network, Chennai, India who has been a sounding board for some of these thoughts. The influence of development in TARAhaat Information Systems Pvt. Ltd. and its “services for the rural market” thinking on DA’s energy and habitat programs is also acknowledged. | ||||

T

T