Governing a Post-2015 World

A

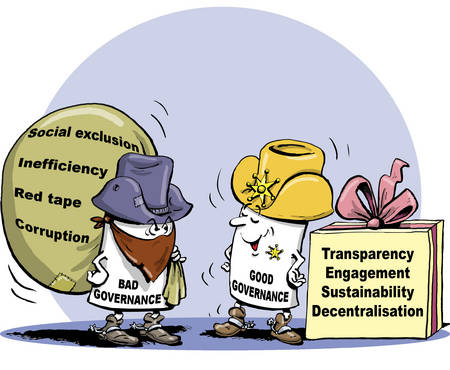

s the global debate on development shifts from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) toward the Post-2015 framework, the uncompromising focus on economic indicators is giving way to a more nuanced discussion of the qualitative differences between developmental paths chosen by states and the need to ensure that economic development is socially, politically and ecologically sustainable. The report of the High Level Panel and the thematic consultations have made it abundantly clear that, if the Post-2015 agenda is to transcend the limitations of the millennial targets, governance must be at the heart of any discussion.Consequences of discounting governance are most stark in conflict-affected and fragile states. If we exclude China, India and Brazil, these states account for almost half the population of the developing world. Not one of them will achieve a single MDG by 2015. Even beyond these extreme cases, the good governance deficit has undermined progress toward the MDGs or facilitated rapid growth while exacerbating second-order problems of economic inequality, social instability and environmental degradation.

Avoiding these pitfalls will

require a radical reconceptualisation of development, respecting the rights

and needs of the individual and the fragility of our natural heritage. This

in turn will require systems of governance that are responsive,

accountable and open. Widening spaces for public participation in

the design, delivery and monitoring of policies and programmes, and making

the institutions of the state more accessible can improve outcomes in

development and service delivery while reducing the scope for corruption and

the abuse of human rights. Participatory decision-making can help remove

structural inequalities and the pe rceptions

of institutional bias that tear at the social fabric and precipitate

conflict.

rceptions

of institutional bias that tear at the social fabric and precipitate

conflict.

In this regard, India has come a long way over the last fourteen years. The Right to Information Act (RTI), 2005, stands out as the signature reform creating a globally admired transparency regime to improve governance at the local and central level. Under the RTI regime, schemes for poverty-alleviation and socio-economic development such as the NREGA, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan and the Mid-day Meal Scheme have been subjected to ever-greater levels of scrutiny and the emergence of the social audit has helped reduce leakage and policy mismatch

1. Meanwhile, access to Environmental Impact Assessments has helped civil society challenge the destruction of the natural environment for large-scale industrial developments.Though these are promising, significant challenges remain. Pendency rates are high and growing, State Information Commissions are understaffed and though the culture of reactive transparency (responding to RTI applications) has spread, proactive transparency (publishing information without being asked for it) is still a distant dream in most places. Records management systems are creaky and the most oft-cited reasons for noncompliance with the RTI Act are lack of training and inability to locate documents

2. Though new technologies provide an opportunity for making these systems more efficient, low internet penetration necessitates reliance on offline distribution of information. These problems suggest that the challenge of reforming governance, in India and elsewhere, will require a concerted effort to build not just a corpus of strong legislation but a culture of transparency.Though they transcend the humdrum of party politics, efforts to build good governance are far from apolitical and necessarily imply a restructuring of the balance of power between citizen and state. This is itself an incredibly complex and drawn out process and points to the need to avoid the rigidity that has dogged the MDGs. It is almost impossible to develop a universally acceptable set of indicators. variations in initial conditions and initial endowments of technology, institutional capacity and citizen voice mean that some states will simply take longer than others and the process will involve a certain amount of trial-and-error. The agenda must therefore be sure to incorporate governance in a way that respects the need for flexibility, persistence and, above all, patience. q

Satbir Singhsatbir@humanrightsinitiative.org

Satbir is a specialist in governance, transparency and rights. He has worked with DfID, Minority Rights Group International and the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative.

Endnotes

1

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057231708000295

2

http://rti-assessment.org/interim_report.pdf