|

From GDP to Wellbeing – for

the People and G overnments’ world over have long held the view that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the main tool, the primary indicator for measuring a country’s economy. It is an index that measures the value of all goods and services produced in the country, regardless of industry. This unit of measure brings down a country’s potential and reduces everything to a numeric value, governed by the ‘principle of more’. GDP is a benchmark of economic and in effect social progress.So, the question really is, when did GDP emerge as an indicator of economic well-being instead of being a measure of economic activity? Presumably when world over, governments began to identify growth with development; when they began to believe that increases in total national incomes, increases incomes at all levels. It’s in the need to simplify accounting and benchmarking we have overlooked the limitations and inadequacies of this index and the growth model it advocates. The most often noted is the

fact that GDP can only add, it makes no distinction between beneficial

and harmful economic activity. So for example, gun sales to children,

oil spills, post-disaster reconstruction all generate new economic

activity and all count as additions to GDP. Accelerating the depletion

of precious non-renewable resources like oil and coal accelerates GDP

growth even as it destroys the essential resource on which that growth

depends. As nations strive for more in the name of economic well-being,

a large part of the costs of these efforts are being passed on to nature

and future generations. Global economic development over the last two

centuries have been largely achieved through intensive, inefficient, and

unsustainable use of the earth’s finite resources. As an indicator, GDP

continues to ignore these implications.

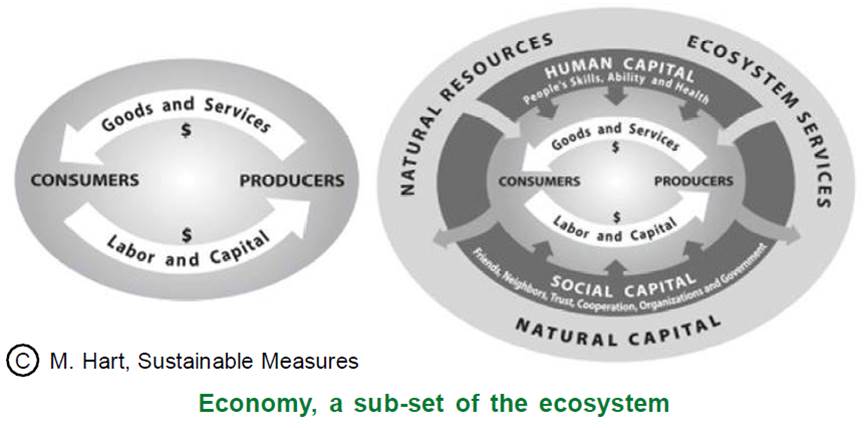

This measure only takes into account monetary transactions related to the production of goods and services, and therefore it provides an incomplete picture of the system within which the human economy operates. GDP is silent on distribution, as this measure doesn’t care if growth is captured by a few or is widely shared. There is a need to go beyond this dominant metric of development and adopt a measure that not only takes into account human capital (for instance the Human Development Index or the Gross National Happiness Index) but also accounts for and tracks our natural capital, our ecosystem services. There are several good examples in the form of indicators that have come up recognising the need to go beyond GDP. For instance, the Genuine Progress Indicator takes into account the health of a nation’s economy by incorporating social and environmental factors. The Happy Planet Index that measures environmental efficiency with which human well-being is achieved. Subjective life satisfaction and life expectancy defines human well-being and the ecological footprint defines environmental impact. The other one that comes close to accounting for both social and environmental impact is the Social Progress Index (SPI). SPI measures the extent to which countries provide for the social and environmental needs of the citizens. Paraguay will be the first country to adopt the SPI by incorporating it into its national development framework. Costa Rica may follow suit. These indicators although easily available have not yet found their rightful place – as an alternative for countries to measure well-being for the planet and its people and move beyond conventional wisdom associated with economic growth. This transition would require a paradigm shift, a shift in thinking that helps individuals, communities, governments, and countries move beyond output and focus on sustainability. A first step towards this would be to account for what matters in the long run – our environment, our natural resources, our happiness, and our well-being.q Gitanjali Kumar

|