|

The Importance of

Information in C limate change is a global challenge having serious repercussions on the Indian economy. Climate change impacts such as rising temperature levels and increasing incidences of extreme climatic events are likely to pose serious threats leading to food shortages, degradation of natural resources, and increase in vector borne diseases. Therefore, adapting to climate change is a growing yet essential necessity, particularly for developing countries like India.A large amount of research has

been done nationally and internationally to cope with climate change

impacts in climate sensitive regions. However, there is a need for

communicating climate change issues in locally relevant and culturally

appropriate ways. Another gap that needs to be addressed is the

inadequacy of the current institutional capacities to mainstream locally

relevant adaptation concerns into the policy and practice framework.

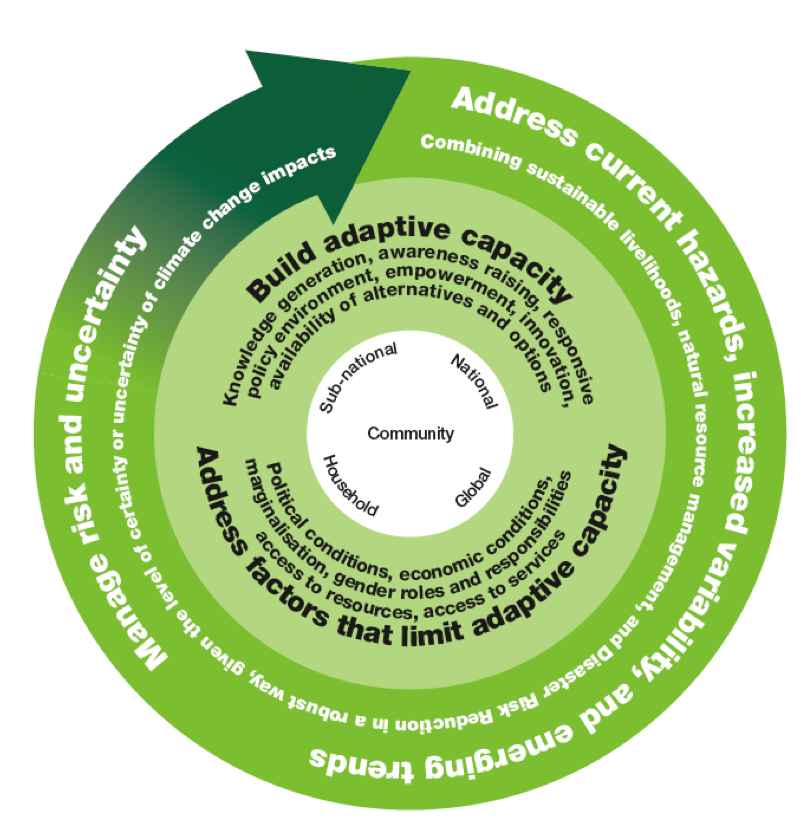

We, at Development Alternatives believe that anticipatory adaptation measures can progress from the top-down approach, through regulations, standards and investment schemes. These components need to focus on improving information, strengthening institutions, and devising strategies for reducing the negative impact on vulnerable population groups. This requires embedding adaptation strategies within the existing national policy and institutional framework, enabling integration of climate change issues with other issues that drive the economic and social sectors. In semi-arid regions, such as Bundelkhand, climate change adaptation measures need to address changes in hydro-meteorological trends, and extreme weather events, in particular. In the semi-arid regions of Bundelkhand, Development Alternatives has identified gaps in the current practice-policy links and integrated robust climate resilient adaptation measures into the policy development. The first initiative (CDKN Shubh Kal - From Information to Knowledge and Action) focuses on the current systems and institutions enabling information and knowledge for climate change adaptation to reach the vulnerable communities of the region. In doing so – it also looks at the existing policy frame at the state and national level. The second initiative (DA- Swiss project on ‘Sustainable Civil Society Initiatives to Address Global Environmental Challenges’) aims to identify strategies to support policies, programs and institutional structures in the Bundelkhand region to integrate climate science in decision-making for climate resilient development. The Bundelkhand region in

Central India, pertaining to its fragile geophysical system is

significantly sensitive to climate change as also one of the most

backward regions of the country. The above-mentioned studies suggest

that currently, actions at the state and national level have made

initial steps to explicitly address climate change issues. At the

national level, the National Action Plan for Climate Change formulates a

plan of action through the establishment of eight national level

missions that focus on promoting understanding of climate change,

adaptation and mitigation, energy efficiency and natural resource

conservation. At the state level, the draft report of Madhya Pradesh State Action Plan on Climate Change (MPSAPCC) focuses on devising appropriate adaptation guidelines with the aim of strengthening the developmental planning process of the state to adequately address climate change concerns (GoMP Climate Change Cell, 2012). The plan identified ten climate change sensitive sectors, three of which (forestry/biodiversity, water resources, and agriculture), are directly pertinent to the Bundelkhand region. The MPSAPCC also ensured that grassroots voices were taken into account through an extensive consultation process. However, some unanswered issues remain that impede the adequate planning and implementation of climate resilient strategies at the ground level. At this stage, the MPSAPCC contains strategies that are on paper and are yet to be mainstreamed in policy and planning processes gap. The strengthening of the MP Climate Change Cell and the operationalisation of the Knowledge Management Centre will support a two-way policy dialogue and effectively bridge the gap between scientists, communities and decision makers. There is an urgent need to use an integrated approach so as to enable a convergence between government departments (e.g., Agricultural and Irrigation Departments) and planning agencies (e.g., District Planning Commission) and across their various governmental levels (e.g., village, district, state, and national).Current plan and scheme development, however, is conducted on a 5-year scale, at best, and often done separate of other departmental planning, which sometimes leads to contradictory policies. Finally, communication and information capacities in the region are lacking. The project findings highlight the fact that the agriculture departments of each district have prepared contingency plans to advise farmers on appropriate adaptation responses in the situation of a delayed or deficient monsoon. Advice includes implementing measures such as using improved crop management techniques, and practicing soil nutrient and moisture conservation measures that can help to mitigate the potential impacts of different rainfall situations. However, there is evidence that the dissemination of this information to the grassroots farming communities is limited for several different reasons. First, outreach is limited due to staff limitations within extension agencies. There are simply not enough extension agents, such as Rural Agriculture Extension Officers (RAEOs) at the grassroot level to address the information needs of the entire area for which they are responsible. Each RAEO is in charge of providing extension to around 1-5 villages, but these agents often do not adequately serve these communities because of lack of dedication and adequate skills. For many farmers, their only option to receive beneficial information and scheme assistance is to travel directly to the appropriate extension agency. Often, farmers find that the cost (both in time and money) of traveling to these locations is not worth the perceived benefit that they will receive from their efforts. This is further hindered by their inability to navigate through several administrative obstacles such as lengthy paperwork and procedures. Other such findings stress that even though the planning at the policy level is taking climate change concerns into consideration but as it reaches the local level, the authorities are interested more in the practical implementation of the schemes/plans. They are chiefly unaware of the concept behind the formulation of the particular scheme. Although several adaptation measures have been implicitly included in many parts of the planning process (i.e., watershed management plans, irrigation schemes, agricultural development schemes), inefficient delivery mechanisms at the ground level and communication gaps has led to weak implementation of schemes at the most crucial bottom level. Therefore, efficient delivery mechanisms need to be strengthened (by frequent trainings, exposure visits to model villages and regular monitoring of the Government officials) so as to ensure the sustainable execution of concrete options at the bottom level. Addressing these issues will require increasing the institutional capacities of local level departments (village and district), collaboration between governmental departments in scheme development and additional focus on more long-term climate adaptive planning. Finally, the communication of climate change related information needs to be enhanced to enable both communities and local level governmental departments to adequately respond to the threat posed by climate change on the region. q Harshita Bisht

|