|

Advocacy for Household

Water Treatment and

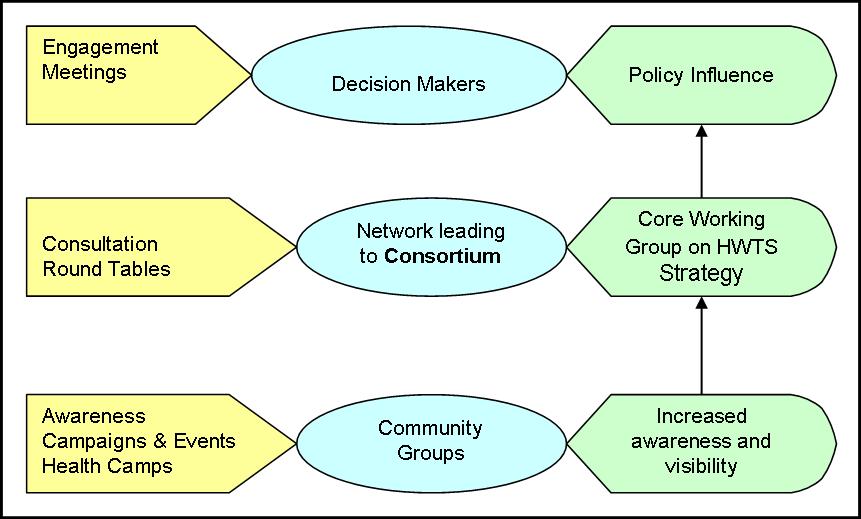

P A WHO-UNICEF sponsored study (Water Supply & Sanitation, India Assessment 2002) stated, with regard to water coverage, that 26 to 31 per cent of the rural and 7 to 9 per cent population remain unserved. Where a distribution network is available, low pressure and intermittent operation lead to back-siphoning and contamination of the water. Hence, there is a need to introduce simple and affordable water treatment methods at the household level to the population exposed to contaminated water. The lack of clean and safe drinking water, together with insufficient personal hygiene, is the root cause of the high child mortality rate as well as of loss of productive time and national income in India. Thus, the main problems to be solved by this project are insufficient drinking water quality and lack of awareness regarding the importance of personal hygiene that both affect the health of the poor population. Hence, the final beneficiaries are typically poor communities both from rural and peri-urban areas and slums that have no access to safe drinking water. About 91% of the urban population in India has got access to water supply facilities. However, this access does not ensure adequacy and equitable distribution.1 Average access to drinking water in Class I towns like Delhi is 73%.2 Poor people in slums and squatter settlements are generally deprived of these basic amenities. Often, water is available, but contamination at source and during transportation to households makes it unfit for human consumption. In India, over 170 million people do not have access to safe drinking water.3 Only 24 percent of the total population is served by a household connection. The remaining 76 percent rely on surface water, private or public dug wells or boreholes, rainwater harvesting or other sources. While efforts have been made to improve water supplies in both urban and rural areas and water may be safe at the point of treatment or distribution, this water is subject to frequent and substantial microbial contamination by the time it is ultimately consumed.4 While water in India is known to have severe problems of fluoride and arsenic contamination in a few regions, it is microbial organisms that constitute the most rampant type of contamination according to surveys of water quality throughout the country.5 Poor availability of good quality drinking water leads to a high risk of water-borne diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever, hepatitis A, amoebic and bacillary dysentery and other diarrhoeal diseases. The Planning Commission of India has estimated that each year, between 400,000 and 500,000 Indian children under age five die of diarrhoeal disease.6 Figures from India’s Central Bureau of Health Intelligence show that the incidence of diarrhoea, enteric fever, viral hepatitis, and cholera has not decreased over the last ten years.7 These kinds of health problems in adults though considered to be common ailments, lead to physical (pain, suffering, fatigue), mental (agony, distress, distraction) and financial losses (in terms of livelihood/employment days and expenses on treatment). Thus, addressing the widespread problem of microbial contamination as a priority can have far-reaching effects in reducing waterborne diseases and child mortality. While practices for drinking water treatment at the point of use, such as boiling and chlorination are known, practice amongst users is not very rigorous. There are certain operational issues that impede the widespread use and impact of these techniques. For instance, the dosage of chlorination is critical, but often not correctly administered by users. Also, the hydrophilic compounds used are often rendered ineffective before application itself owing to undue exposure to moisture. Boiling entails expenditure on fuel in an already energy and cash-starved household, and it is an accident-prone methodology. Between July 2009 and August 2011, Eawag (http://www.eawag.ch/index_EN) and Development Alternatives with the help of local partner organisations implemented the project "Provision of safe drinking water in slums of Delhi, India through point of use (P-O-U) treatment method – SODIS." The project benefited children and adults living in the urban slum areas of Delhi. The goal of the project was to improve the health situation in the target communities, schools and families. Intensive community engagement and mobilisation over the project duration was the key to the success of the project. The uptake of SODIS (http://www.sodis.ch/index_EN) in slum areas shows that an attitudinal change was brought about among households to willingly adopt this method. A diverse range of experiences have emerged based on the approaches taken during the implementation of SODIS Project. This project aims at providing an inexpensive solution for the provision of safe drinking water at the point of use (P-O-U). SODIS or SOlar DISinfection is a low-cost, simple method to disinfect drinking water using sunlight. UV rays penetrate bottles, killing micro-organisms and making the water safe for consumption. This project has been focused towards bringing about behavioural change and establishing communication with the community in order to encourage the adoption of SODIS and other point-of-use water treatment technologies. The implementation was done through networks and local partners. SODIS promotion is being carried out in selected slums of Delhi by Development Alternatives (DA) and its implementation partners Ehsaas Foundation and Indian Society for Applied Research & Development (ISARD). The project is supported by Eawag. The focus of the project activities is on awareness generation for behavioural change. Based on the initial baseline survey and exhaustive water quality monitoring, 18 slums were selected. The target was to sensitise 10,000 households (HH) in these slums. The sensitisation was primarily carried out through door-to-door community mobilisation by SODIS anchors. Training of SODIS anchors had been organised, equipping them with information and tools for dissemination. For awareness generation, various tools and techniques, for example, IEC material, stickers, flyers, nukkad natak, wall paintings and radio shows had been adopted and planned by both the implementing partners in association with DA. Seasonal collections of raw and SODIS treated water samples for bacteriological contamination testing were also performed by both the DA team and NGO partners. SODIS anchors visited the clusters on a weekly basis. Regular visits were made by the DA team (2nd tier of monitoring) to ensure that the households are following SODIS regularly. Advocacy was carried out at two levels under the project: i.e., end users and intermediaries, as well as policy / decision makers in the government. Throughout the duration of the project the major focus on the former stakeholder group. This group consists of Anganwadi workers; ASHA centres, sewing centres and other groups. At the end of the project activities, studies showed that there was approximately 96 per cent awareness on the significance of water quality for good health and almost 70 per cent slum households related diarrhoeal diseases to poor water quality. Prior to SODIS advocacy, 60 per cent populations consumed direct water supply while after SODIS advocacy, 30 per cent population consumed direct supply. This showcases the impact of the mobilisation created in terms of behaviour change among target communities. Overall, 74 per cent households were found to be SODIS users out of which 38 per cent were regular users and the other 36 per cent were irregular users. The populations consuming boiled water during monsoon and non SODIS days increased from 18 per cent to 45 per cent in South West Delhi slums while in East Delhi it increased from 25 per cent to 45 per cent. Out of the total surveyed household 36 per cent had experienced a positive change in their health status after using SODIS and 29 per cent households experienced a reduced incidence of diarrhoea among the children. Among the health impacts, reduced stomach ache is the most prominent, observed in 44 per cent of total households showing positive health change. Good hygiene at the personal and community level is a prerequisite for SODIS efficiency; however 92 per cent of the households had unsatisfactory conditions, mostly because of factors outside their control such as clogged and overflowing drains. This has a negative impact on the overall health status of the communities. Palatability contributed very significantly to the demand for SODIS water. Approximately 56 per cent of households in both slum zones found SODIS water sweet like mineral water, unlike boiled water that was bland or direct supply water, which is sometimes considered to have an undesirable smell. After SODIS advocacy, almost 80 per cent slum households expressed the need for a House Water Treatment System (HWTS). The positive and encouraging response and learning received from the project makes it imperative to scale up the promotion of SODIS in the context of an integrated HWTS which includes other methods such as boiling and chlorination for large scale awareness and behavioural change. Development Alternatives is now working on a project called "HWTS Advocacy Strategy among the Bottom of the Pyramid in India with a Focus on Delhi National Capital Region," funded by Eawag Solaqua for one and a half year, to advocate for the integrated HWTS. In order to achieve this scale up, concerted efforts are needed for engaging and involving various stakeholders that can act as catalysts, facilitators and help achieve a broader and more sustainable result as well as converging efforts with existing schemes and initiatives that promote safe drinking water. There is a need to enable stakeholders at the policy level as well as users to make informed decisions about HWTS systems. Currently, there is a knowledge gap in this arena. This HWTS project aims at filling this lacuna by advocating for HWTS systems among concerned policy makers and providing information to end users about various options available. The aim of taking forward HWTS options including SODIS, boiling, chlorination etc. through this advocacy project is that low cost methods of access to clean drinking water do not remain theoretical knowledge confined to the project areas. Through scaled up promotion, the idea is accepted and recommended at different levels so that people outside the project area can benefit from it and the incidences of waterborne diseases and child mortality reduces in long run. The main objectives of the HWTS projects are: • To scale up promotion of safe, affordable and environmentally appropriate options for HWTS systems and improved hygiene practices within the broader Government strategy for water systems and supply and diarrhoea prevention. • To increase visibility of appropriate HWTS options (especially low cost options like SODIS) for the urban and rural poor in India with a focus in the Delhi National Capital Region of India (which includes Gurgaon, NOIDA, Greater NOIDA, Ghaziabad, and Faridabad). The targets for intensive interventions under the project are urban slums and other poor habitations in the Delhi National Capital Region (NCR) of India. As of 2009, the population of Delhi is estimated to be around 18.5 million. The National Institute of Health and Family Welfare estimates that about half of Delhi’s population resides in urban poor habitations of which 30 percent live in urban slums. The poor in slum areas are vulnerable to health risks as a consequence of living in a degraded environment, inaccessibility to health care, irregular employment, widespread illiteracy and lack of negotiating capacity to demand better services.8 Additionally, Delhi, the capital region of India, is the base for relevant government departments as well as numerous capable NGO’s and international organisations working on the provision of safe drinking water. It is thus ideally placed for any successful strategic plan for the provision of safe drinking water to have a ripple effect in the rest of the country. q Dr. Uzma Nadeem (Endnotes) 1http://www.ddws.gov.in/sites/ upload_files/ddws/files/pdfs/XIPlan_BHARAT20NIRMAN.pdf. 2 http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/11th/11_v2/11v2_ch5.pdf. 4 Wright J. et al. (2004) ‘Household drinking water in developing countries: a systematic review of microbiological contamination between source and point of use.’ Tropical Medicine and International Health 9(1): 106-17. 5 NEERI (2004) ‘Potable water quality assessment in some major cities in India’ JIPHE, India (4): 65. 6 Water Resources Division (2002) India Assessment 2002: Water Supply and Sanitation, New Delhi: Water Resources Division, Government of India Planning Commission. 7 Mudur G. (2003) ‘India ’s burden of waterborne diseases is underestimated’ British Medical Journal 326:1284. 8 Evaluation of MAMTA Scheme in National Capital Territory of Delhi (2010), Department of Planning and Evaluation, Department of Health and Family Welfare-New Delhi.

|