| Low Carbon Pathways:

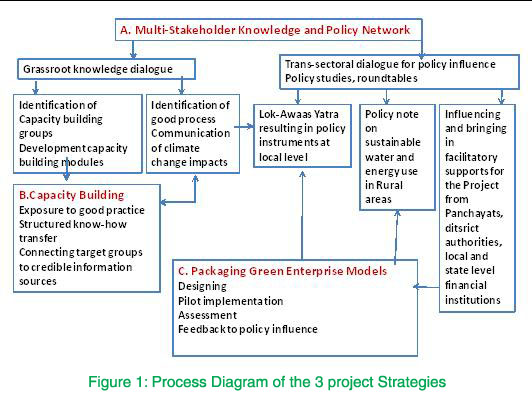

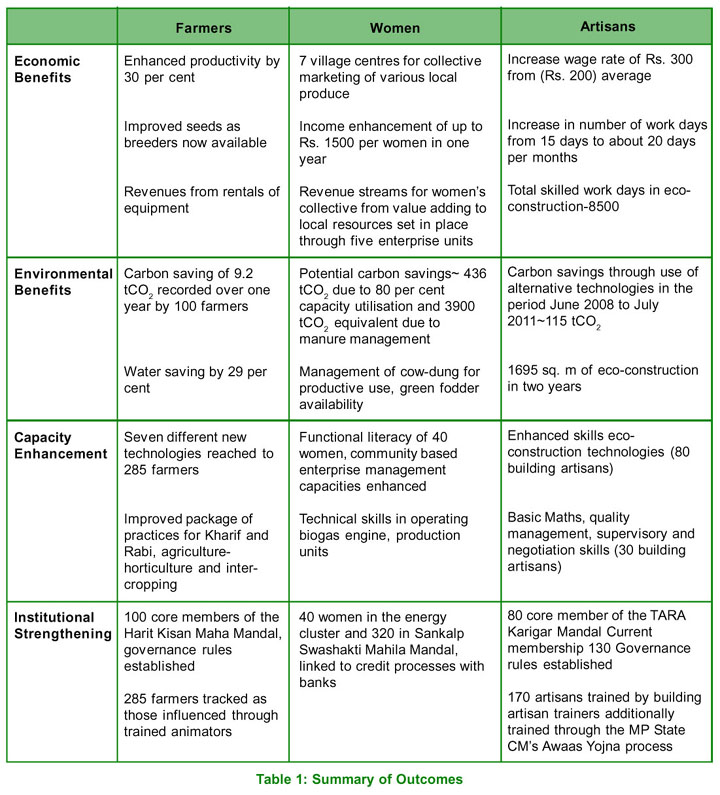

Introduction Bundelkhand in Central India, comprising of seven districts of Uttar Pradesh and six of Madhya Pradesh, is a region with recurrent droughts, crop failures and increasing uncertainties of life-sustaining monsoon. It is one of the most backward regions in India and ranks very low on almost all development indicators. The Sustainable Civil Society Initiatives (SCSI) to address global environmental challenges has made an attempt to influence vulnerable communities, local administration and facilitating agencies in the public sector towards development to enhance the adaptive capacities of the communities of Bundelkhand in the face of adverse environmental conditions. The initiative is designed as a part of Development Alternative’s "Shubh Kal Campaign"1 wherein the organisation has set about understanding climate vulnerability; identifying development gaps; and designing and testing institutional, technological, social and market based mechanisms towards meeting its goal. The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), Climate Change and Development Division, Embassy of Switzerland, India has collaborated with DA in this endeavour. The project was designed with long term objectives to "to eradicate poverty on a large scale in Bundelkhand without destroying the environment" indicated by "enhanced incomes, reduced carbon footprints and regenerated resource base in 1000 villages of Bundelkhand, India. The initiative has promoted efficient resource use and enhanced income for small and marginal farmers, women’s collectives and building artisans by a synergy of indigenous and scientific knowledge. The process has also involved packaging of technology based measures into market-based viable economic models for the target communities, financial investments and business initiatives leading to benefits of enhanced incomes and reduced green house gas emissions. The formal meeting with Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) from the region revealed the need for sharing knowledge and collaborative action towards improved agriculture and livestock to reduce livelihood vulnerability in the region. The Bundelkhand Knowledge Platform (BKP-www.bkpindia.net) has been initiated to facilitate engagement with stakeholders for effective participation in actions related to drought alleviation in the region. It has also helped in engaging with the state-level and national partners for dialogue on climate change mitigation and adaptation. Strategies Adopted The project has adopted a three pronged strategy. a) Knowledge sharing facilitate change in practice and to influence policy b) Intensive training and capacity building c) Development of sustainable, community-based enterprise models The project implementation involved systematic steps across all three clusters, according to the capacity and the readiness of the communities in each. Nine processes (or steps), critical to implementation of the project at the grassroots and for connecting to policy, were identified (Fig 1). The SCSI worked with farmers, women and building artisans. So far, 285 farmers have shifted to improved practices of agriculture such as resilient seed varieties, line sowing, reduced tillage, drip irrigation and sprinkler systems that have resulted in savings in irrigation and also prevented loss of seed and crop when the rains have been delayed as in 2009. An increase in productivity to the tune of 30 per cent has been marked. The reduced irrigation has resulted in energy saving coupled with practices of reduced tillage, agro forestry etc, and have led to a calculated savings in carbon emission (Table 1). Challenges While SCSI achieved commendably in the past 36 months many challenges lay ahead to both the sustainability of the operations of the small community clusters as well as replication of good practices across the region. The packages of improved agricultural practices collated under the project have to be taken up by institutions such as the Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) for replication. Replication, however, is also dependent on favourable policy measures in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. The Bundelkhand Knowledge Platform (BKP) needs wide ownership for it to be able to influence practice and policy. The potential linkage with government’s Bundelkhand Package remains a challenge for the project, further aggravated by procedural lapses, external factors and mandates of agencies not in project control. Bundelkhand has tremendous potential with its diverse natural resources, a workforce trained in traditional agriculture and artisanship, and a rich indigenous time-tested knowledge base. This base remains an untapped resource, particularly in terms of regeneration of water and soil. The formalisation of three associations and their continued capacity building and hand-holding will be required for another couple of years, at least till such time as the revenue cycles support the auto-management of the institutions. The effective demonstration of these models will also be critical for influencing policy processes. The current community based institutions have to be oriented to become service providers for promoting low carbon climate resilient growth in their own as well as other villages. Energy efficiency has led to reduction in emissions of carbon dioxide. The reductions in all three clusters are being tracked and quantified and can, in principle, help in securing access to carbon finance. No formal system of seeking finance for eco-construction exists so far. The activities of farmers and women’s clusters have been compiled as Programme of Activities Designed Document (PoADD) and submitted for the host country’s approval to the Ministry of Environment and Forest (MoEF). Their future will depend as much on quantum replication and engagement with potential carbon buyers as on national and international carbon market situation in a post-Kyoto world. As such, to base sustainability of the green social enterprise on availability of carbon finance appear to be impractical – these can at best be considered bonus if they do materialise. There is an immediate need to service policy processes that enable rural communities, entrepreneurs and institutions to access public funds through government schemes and programmes, credit supports to adopt sustainable livelihood practices. q Dr. Uzma Nadeem Reference 1. Report on "Drought Mitigation Strategy for Bundelkhand Region of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh" by Dr. J. S. Samra of the National Rain-Fed Areas Authority, 2008.

|