|

Sustainable Lifestyles W e define ourselves, our happiness, our achievements by our lifestyles - the way we live. A good lifestyle, something we all aspire to achieve, has come to be defined by how much we consume - the more the better. However, our lifestyles are built on a limited natural resource base, with unsustainable consumption patterns and incessant population growth further exerting excessive pressure (SERI, et.al., 2009).

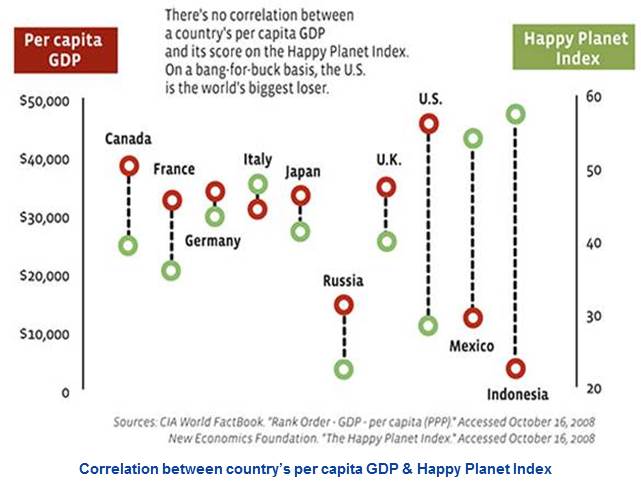

In a free market economy, consumption patterns drive production. Advertise-ments and marketing today have made societies believe that higher income and higher possessions will lead to happier lives (Trott, 1997). The youth have become a key focus of marketing strategies due to the sheer size of the target group. India is one of the youngest countries in the world today with approximately half of all Indians (nearly 50 crore) below 25 years (Srivastava & Khullar, 2012). Furthermore, it is estimated that nearly 250 million people are set to join India’s workforce by 2030. The result of this is a considerable increase in disposable incomes leading to conspicuous consumption (Harjani, 2012). However, research has established that above a certain threshold, an increase in material wealth does not improve life satisfaction any further (Bentley, et.al, 2004). The figure above confirms this research by showing negative correlation between GDP per capita and the overall happiness quotient of different countries. The Post-2015 development agenda can play a crucial

role in influencing this young workforce to adopt sustainable lifestyles

by promoting sustainable consumption. Although Goal 7 of the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs) was to ‘Ensure Environmental Sustainability’

(UN, 2000), there was no target that aimed at reducing unsustainable

consumption patterns. The UN Secretary General’s High Level Panel on the

Post-2015 Development Agenda specifically mentioned that the MDGs fell

short by ‘not addressing the need to promote sustainable patterns of

consumption and production’ ( Sustainable consumption is defined as "the use of goods and services that respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life, while minimising the use of natural resources, toxic materials and emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle, so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generations" (IISD,n.d.). Hence, it does not advocate ‘stop consuming’ but ‘doing more and better with less’, through the reduction of resource-use, degradation and pollution, while increasing the quality of life for all. Sustainable consumption cannot be imposed upon people; it is choice they will have to make (Robins & Roberts, 1998). The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) launched initiatives like Education for Sustainable Consumption and Sustainable Lifestyles and Youth to promote rational and responsible use of natural resources, equitable socio-economic development and a better quality of life for all. It aims to create a new and aware generation of young people who incorporate sustainability in their personal and professional decisions (Thoresen, 2010). It is important that sustainable lifestyles be introduced in the early years and continues right up to university education programmes and professional and vocational training programmes. The media and internet are very powerful tools to shape young minds. UNEP and UNESCO have used these resources and have developed an online training kit on responsible consumption for young people - the YouthXchange: Towards Sustainable Lifestyles. It is designed to support youth groups, schools and NGOs to spread the message of consuming within the planetary boundaries. It offers examples of more sustainable purchasing choices and most importantly, empowers young people to put theory into practice (UNEP, n.d.). Education can only empower and enable young people to make informed choices. Ultimately, it is in the hands of the policy makers to encourage promotion of sustainable consumption amongst the youth. q Seher Kulshreshtha References • IISD (n.d.) Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption. • M. Bentley, J. Fien & C. Neil (2004) Sustainable Consumption. • M. Trott (1997) Sustainable Consumption • N. Schoon, F. Seath & L. Jackson (2013) One Planet Living • P. Srivastava & A. Khullar (2012) How well do Indian marketers understand the Indian youth? • SERI, GLOBAL 2000 & Friends of the Earth Europe (2009) Overconsumption? Our use of the world´s natural resources. • United Nations, (2000) Millennium Development Goals and Beyond 2015. • UNEP (n.d.) Youth: UNEP/UNESCO YouthXchange Initiative. • VW. Thoresen (2010) Here and now! Education for Sustainable Consumption. UNEP.

|

Schoon, et. al. 2013).

Schoon, et. al. 2013).