Watershed

Approach : A Livelihood Option ?

|

After

decades of initiatives in eliminating rural poverty through various programmes

that were primarily sectoral based and met with limited success, the new

approaches to rural development are increasingly adopting an integrated cross-sectoral

approach. Sustainable use of natural resources is seen more and more as a means

to ensure livelihoods. In recent years watershed management has increasingly

become the focal point for poverty alleviation and drought mitigation

particularly in rain fed areas of India. Around 170 million hectares of land in

India are classified as degraded, roughly half of which falls in undulating

semi-arid areas where rain-fed farming is practised.

The article has attempted to examine the watershed approach in detail, both at

the field/ground level as well as at the policy level and make suggestions for

its adoption as a viable option for meeting the livelihood needs of the focus

group, especially the vulnerable communities.

Government

Programmes

The concept of "Watershed"

as the planning unit for development of natural resources is effective and the

watershed approach has gained significance since 1974 with various initiatives

by the Government through DPAP, DDP, IWDP and NWDPRA programmes. These

programmes were basically adopted a ‘Top-Down’ approach which lacked

participatory planning and in which importance to sectoral issues like

agriculture, wasteland development, soil conservation was accorded priority thus

they did not prove effective and successful. As a result, a need was felt to

design a new Watershed Guidelines in 1995 with more thought on people’s

participation, a bottom-up approach at various levels of the project cycle, and

also their integration with other employment generation and poverty alleviation

programmes for generating more livelihood options for the focus groups.

The Watershed Framework recognises five capital assets where people can

draw upon human, natural, financial, social and physical resources. Although the

watershed programme spells a new initiative, however there are some emerging

issues, mainly related to livelihoods of vulnerable communities, which need a

greater focus. These include:

| w |

How watershed

activities affect the livelihoods of vulnerable groups? |

| w |

How and why do their

interest and participation differ? |

| w |

How watershed

programmes interface with livelihood strategies and the migration factor? |

| w |

How are the enhanced

benefits from common land and other biophysical resources shared? |

The above issues are analysed and

addressed on the basis of past experiences of implementation of watershed

projects.

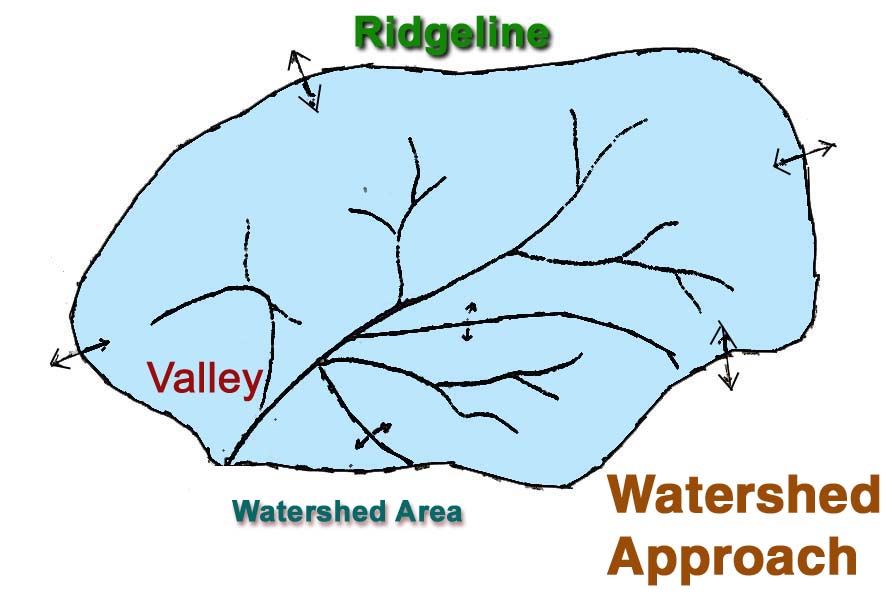

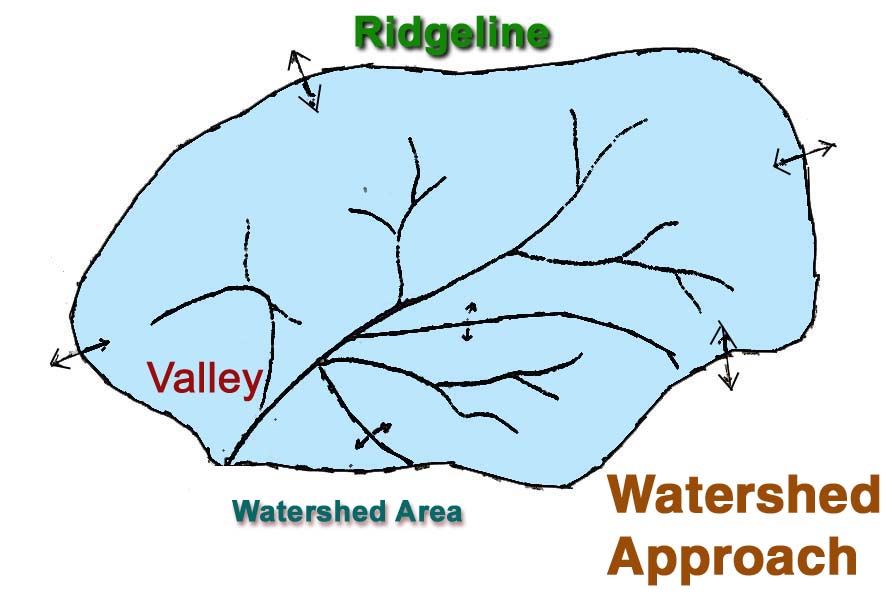

Watershed programmes are

generally implemented by adopting Ridge to Valley approach for

rehabilitation. The approach may work against the interest of the poor who often

have their small land holdings in the upper slopes, after rehabilitation and it

benefits the well off farmers whose lands are located in the down stream valley

areas. Though the poor benefited only through the construction of

physical capital, mainly from soil and water management (such as bunds, check

dams, gully plugs, ponds, shallow wells, and afforestation activities as casual,

unskilled employment opportunities) they still remain as labourers and rely on

village commons. The increased crop yield alone would not solve rural problems,

as long the economic environment for rural people still remains adverse. This

imbalance in equity of sharing resources means that the better off would capture

the lion’s share of benefits generated through rehabilitation. However, it

help in checking the seasonal migration to some extent during rehabilitation

period. (See box for details)

Major learnings from

Watershed Programmes

Participation

by the focus groups during planning and management of the programme is

not encouraging due to the existing socio-economic obstacles and feudalistic ‘leader-follower’

system prevailing in the country (Laxminagaram Watershed, Kurnool district,

A.P.). Despite their participation at various levels, the needs and

aspirations of the focus groups could not be taken care of in the programme

design.

Common Property Resources

or CPRs in reality do not exist in many areas. Even if

they do, it is in a highly degraded form and often the only assets of poor to

meet their fuel, fodder and other livelihood needs. After watershed

rehabilitation, the increased potential of natural resources often attracts the

attention of the landlords for encroachment and denies the access (and

entitlement) to the poor. This leads to an increase the vulnerability as well as

disparities within the community.

|

Financial

Capital Establishment of

credit groups (Self Help groups) to empower women within the watershed area was

a good initiative but the multiplication strategies have to be worked out for

sustaining the livelihood options of the focus group including women. |

|

"Watershed"

is an area covered by a ridge or stretch of highland dividing the

area drained by different rivers/streams. It comprises not only its

boundaries but also its people, birds and animals, vegetative cover and

forests, soils and rocks, its topography, water and mineral resources

and its climate within a well defined ridge line as its boundary. |

Policy

interventions required for success of Watershed Programmes

The lacunae in the present

approach as analysed above could be overcome to a large extent through the

following interventions, while ensuring participation of the stakeholders in the

implementation would also address the issues of usufruct rights and livelihoods

of vulnerable communities in particular.

1.

Participatory planning The roots of poverty in

India are tied up in power and lack of entitlements and access to natural

capital by the poor. The programme should be people-centred. Hence while

planning and designing the watershed programmes, one has to understand and

consider the dimensions of poverty and vulnerability, needs and priorities,

existing skills to support the livelihoods of stakeholders to achieve a positive

direction of change through the programme. To start with, an analysis of people’s

livelihood needs and how these have been changing over time has to be worked out

by adopting participatory approaches. Sometimes it is a crucial factor while

selecting a watershed area.

2. Common

Property Resources The

focus groups generally have limited land, uncertain access to developed

resources of physical and natural capital and limited access to commons. No

Indian State has a policy to perpetuate the sanctity of common lands to ensure

the ownership over the commons and usufruct after rehabilitation of the CPRs by

the focus groups. There must be an appropriate property-rights structure in

place pertaining to private and government owned lands, before the programme

initiation. This can only be achieved through a proper legislation at the policy

level.

3.

Livelihood Needs Project

intervention in watershed programmes, generally through land based activities

and the rural non-farm sector, has rarely been a focus. It cuts across

stakeholder interests, hence focus should be given to non land-based activities

to address the livelihood options. The focus group seeks livelihoods in the

non-farm sector to complement seasonal agricultural incomes as well as to

supplement inadequate agricultural incomes. In order to achieve livelihoods, one

has to understand the livelihood patterns and supporting systems, backward and

forward linkages, viable alternative livelihood opportunities and upgradation of

skills. To supplement this, there is a need to establish a Livelihood

Fund especially for the vulnerable communities and the necessary

modalities have to be worked out at the policy level. q

|

Appareddypally

Watershed in Andhra Pradesh |

|

Watershed programme was implemented (1996-200) by a

local NGO (Villages In Partnership) in a drought prone area called

Appareddypally, approximately 35 Km from Mahabubnagar town in Andhra

Pradesh. There are 375 households with a population of around 2000,

comprising OBCs (85 %), SCs (5%), STs and other communities (4%). The

average annual rainfall is 350 - 450 mm. There are 5 to 10 landless

families and majority of the farmers are small and marginal. There are 50

to 55 bore wells, 100 dug wells and 3 hand pumps existing in the village.

During the programme, 12 check dams, 15 gully plugs, one percolation tank,

15 sunken ponds, one feeder channel and bunding in 40 hectares were

constructed. Around 300 to 350 acres of farmland were brought under a

second crop recently. There were only 10 to 15 acres under the second crop

a few years ago. The social capital developed in the programme includes a

Watershed Committee, Watershed Association, User Groups and 15 Self-Help

Groups (SHG). Each group consists of 15 members and deposits an amount of

Rs 30 every month in a bank. Five groups have received matching grants of

Rs 30,000 each from District Rural Development Agency (DRDA) and taken a

loan of Rs.1 Lakh from the Sangameshwara Grameen Bank. The total turnover

from all the SHGs at present is around Rs 10 Lakhs. The migration was

around 75% before the watershed was initiated, while during the project

period it decreased to 25% due to labour availability in the village. The

situation now has returned to what it was earlier after the completion of

the watershed programme. The main source of livelihood in the village

after the watershed programme remains the same (farming and labour).

However, the community is interested in initiating cottage industries

(candles, incense stick, etc). |

P S

Chandrasekhra Rao