| Women, Habitat and Livelihood:

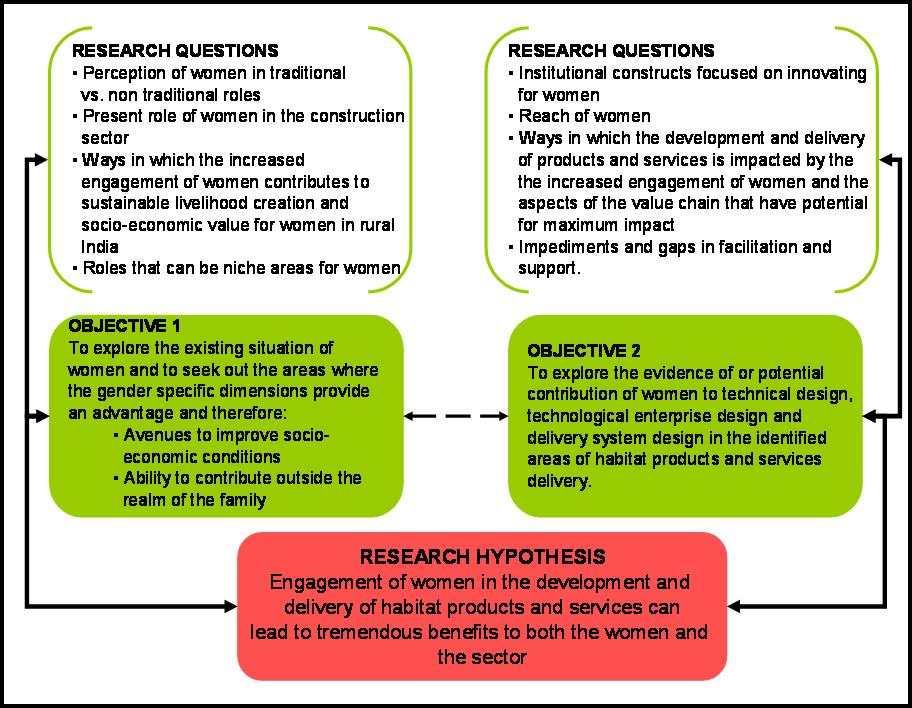

T he findings presented in this article are based on a research study ‘Exploring the Potential of Mutually Reinforcing Role of Women in Habitat Based Livelihood Services’, conducted by Development Alternatives (supported by International Development Research Centre, Canada) conducted over 2009-11. The study addresses the hypothesis that "engagement of women in development and delivery of habitat products and services can lead to tremendous benefits to both the women as well as the sector". The study has concentrated on rural communities where construction sector is an emerging viable option for livelihood creation for men and women and is seen as a poverty alleviation strategy by governments, civil society institutions and other development agencies. Under the broad rubric of involvement and influence of women in innovation processes, the research has attempted to explore the role of women in design, development and application of habitat technologies and technology based enterprise systems for livelihood creation. Its focus has been on the rural habitat and infrastructure which has been identified as a priority sector for rural poverty alleviation in India. The attempt has been to identify specific niche areas where women have a special advantage in terms of design, production processes, and application services; and where these niche areas provide them an easier stepping stone to improved livelihoods in the sector. Along with this, the study aimed at looking at the supporting structures needed to increase participation of women in the sector in a trouble free environment. The value addition of the women’s work is clear in its perceived quality as the women realise the need of work for betterment of their domestic conditions, the value of the products in day-to-day living and the opportunity it provides in working outside the four walls. However, a major impediment is the lack of regular work and its demand. Even when there is demand not all women at all times can be employed. The general perception is that this is due to the lack of government involvement in providing work. Policy measures like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act do provide employment, but they further establish the role of women as ‘helpers to the men’. In the end, women’s contribution to technical design, technological enterprise design and delivery system design is not tangible nor is found to be substantial. The fact is that this type of work (where women are working as skilled labour) is a relatively new phenomenon, especially in the rural space, to make any sweeping statement of women’s contribution to the sector is not possible at this stage. Some impact is being seen, but for the impact to be consistent in nature. The first task is to increase involvement of women in the sector. As the discussion in this chapter reveals, the impact of women working in this sector (as skilled workers) is clearly visible on the lives of women (more specifically in terms of confidence earned through enhanced income and increased ‘say’ in decision making). However, it is too early to talk about the impact created on the sector. There are some instances which make this impact somewhat visible but their frequency is too low to draw any inferences at the moment. For sustainable livelihood creation for women in the sector there are varied things that need to be done, initially at the level of the society and subsequently at the level of the various institutions particularly non-governmental organisations (NGOs), government, market and women. However, even to make all inclusive policies for women in the sector, just research studies will not be enough, rather the women themselves should be made a part of the process, so that ownership and participation of the women is inculcated from the beginning. Social Processes Despite the fact that construction is one of the biggest employer in the country after agriculture, and women consist a huge section of its unskilled labour force, no policy in the country encourages women to take up further training to upgrade their skills, pointing to a gap in awareness and lack of gender considerations in policy making. In a sector like habitat where skilled labour is considered the man’s domain, training women to do skilled work is a revolutionary concept. The need then is to indicate the kind of skilled labour that rural women can provide in the habitat sector. Unless at the very base skill development in habitat services for women is included, their participation will always be informal and haphazard. Their training needs should be identified and recognised by the government, and the areas where their participation is beneficial should be included in skill development programmes. It is also essential that after institutional training there are inbuilt systems for infield training and absorption in the sector. There should be safe commuting and staying places with some initial stipend so that the entire process of training leads to ‘women in action’. Initiatives to challenge traditional gender roles need to be taken. Girls are only trained to be daughters-in-law. No thought is given in rural areas that the girls should be trained in employable skills that can lead them to contribute beyond the realm of the household. To challenge gender roles, women should be educated about labour rights, which should be an integral part of the training programmes. The role of inclusive training and capacity building should not be undermined in creating social change. Institutional Mechanisms Women in rural India usually do not have educational opportunities and exposure to outside world. Thus, lives and aspirations remain confined to the four walls of the house. This actually limits their horizon. It is quite expected that they will take time to come out of rigid boundaries and step into a work area which is male dominated with machines and equipments ergonomically unfriendly to women. This phenomenon is coupled with markets and Panchayati Raj Institutions which are neutral to their existence. In such circumstances, to bring forth women’s latent capabilities the institutions engaging with them need to make attempts to loosen the knots that tie them up. The first step towards this is establishing trust with the community, for which an understanding of the culture is necessary. Once the barriers to the women’s work have been adequately dealt with, a careful assessment of the women being selected is required to ensure their interest in the work. After the women have been identified major challenges come in the form of lack of education among them and the availability of adequate, simple and illustrative training material. Certain mechanisms have to be developed to overcome these challenges. At the Level of Organisations • Initiating a gender inclusive training process, which promotes awareness regarding gender equality and guaranteed rights • Understanding cultural and societal limitations and take steps to challenge traditional gender roles by training women in life skills such as confidence building, negotiating etc • Creating awareness regarding the work • Working in close association with local leaders and panchayats to bring about social change • Standardied training manuals and materials • Realising the potential of women in niche areas like renewable energy and design • Adopting learning by doing approach to ensure maximum retention of skills • Providing certification and identity cards for recognition of work and learnt skills • Creating linkages with the market, credit institutions and government officials to make the women self-sufficient to work as entrepreneurs At the Level of Panchayats • Act as intermediaries to connect the women to market by creating awareness amongst consumers and by placing orders to women groups when habitat services are required • Work closely with the organisations that are training women • Create a conducive and supportive space to work for women in the village • Recognise women that are skilled in habitat services and promote them to train other women and aid them in setting up a local enterprise and self help groups (SHGs) At the Level of Research • Innovate women friendly machines and equipments which help women to take new work areas in habitat services • Conduct case studies to propagate success stories through various mediums like television, books, briefing papers and conferences, among others • Designing of training material which is illiterate friendly and simple in content At the Level of Funding Agencies • Encourage NGO’s and civil society organisations to train women in different kind of work like those seen in habitat services rather than embroidery, handicrafts etc • Play a role in propagating a more inclusive skills development policy to reach out to the policy makers effectively • Aid in spreading awareness on the potential that women can have in certain areas of habitat services and encourage future studies looking into these areas For all these institutional mechanisms to be in place the right policies have to be in place. A policy for women in the habitat sector in the first instance needs to be gender inclusive. The same policy cannot apply to both men and women, especially since their work conditions are and will be different. To conclude, there is an immense need even today to challenge the traditional gender roles defined by society as these create barriers to women’s work. Moreover, women should be trained in a standardised and a socially acceptable manner so that they can be competitive in the market place. Training women on ad hoc basis does teach them the skill, but their work performance, acceptance by consumers and other stakeholders as skilled workers is diluted. Lastly, the involvement of the government and other stakeholders with a long term planning and commitment is must for sustainable results. q Dr Alka Srivastava

|